Italy defined fashion, then it got old

As the founders of luxury brands enter old age, succession planning to protect and build on their legacy gains urgency.

A sculpture of a giant pencil loomed over a recent menswear collection Giorgio Armani sent down the runway. The Italian designer was on the cusp of his 89th birthday, and after the show he ambled over to the pencil, which was emblazoned with his name, and wrapped his arm around it.

“This is to remind me that my work is done by me, and from a blank sheet of paper,” he told a small group of reporters.

For years the fashion world has been on the lookout for signs that Armani, known as “King Giorgio”, might loosen the reins on his luxury empire. Potential buyers range from rival fashion house Prada to John Elkann, scion of the Agnelli family who own Ferrari, according to people familiar with the matter.

But after the show, Armani made it clear he had no intention of relinquishing his throne. “The head is working very well,” he said.

Beyond the House of Armani, a long list of Italy’s vaunted fashion houses are at a crossroads. Many of their designers are pushing past the age of retirement while clinging to the brands they built. Some are hashing out how to manage their legacies. The husband-and-wife team atop Prada, Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli, are in their 70s. Diego Della Valle, chairman of luxury shoe giant Tod’s, turns 70 this year. The co-founders of Dolce & Gabbana, Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce, are now in their 60s.

As Italy’s fashion royalty ages, the era of the all-powerful designer is coming to a close. Armani embodies a generation of designers who wielded broad authority over their fashion houses, from the design studio to the boutique. They are, above all, business owners, calling the shots on corporate governance as well as global expansion.

That business model is under siege. Italian designers, no longer in their creative prime, have to navigate a fashion landscape that is now the province of massive conglomerates. Multibrand groups are deploying their financial firepower to penetrate China and other foreign markets. Designers have become hired guns, brought in to rejuvenate a brand and jettisoned once sales sag. It is an approach investors reward. French luxury conglomerate LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton has a market value more than 20 times the size of its closest publicly traded Italian rivals.

The smaller scale of Italian brands makes them easy targets. Swiss conglomerate Richemont, which owns Cartier, recently snapped up Italian shoemaker Gianvito Rossi. This northern summer Kering, the French group that has long owned Gucci, bought a 30 per cent stake in Italian couturier Valentino with an option to buy the entire brand in the next five years.

Armani and Prada endure in part because they have become cultural icons. In Italy, where they are treated as demigods, the designers cast a long shadow, making it hard for younger Italian designers to emerge.

Talk of succession is largely taboo as brands are intertwined with the public personas of their designers. Prada has reigned so long that trends from her heyday – the 1990s and early 2000s – are now back in style. The lines on Armani’s angular face have softened over the years. But the designer’s combination of black T-shirt, white mane and perennial tan are etched in the public’s imagination. Both designers declined to comment for this article.

Italian luxury has long been defined by fiercely independent, entrepreneurial families that are reluctant to band together. From their perches in Milan, Rome and Florence, powerful fashion clans view each other as rivals rather than potential partners. It is an ethos that stems from Italy’s history as a country of warring city-states. Guelphs and Ghibellines don’t do mergers.

Now the Italians find themselves outgunned on every front. Their French rivals are pouring money into e-commerce operations and artificial intelligence. Brick-and-mortar stores are bigger and more elaborate.

LVMH recently spent hundreds of millions of dollars to renovate Tiffany’s flagship in New York, stuffing the 10-storey store with Jean-Michel Basquiat canvases, an Anish Kapoor wall sculpture and one of Julian Schnabel’s signature broken-crockery paintings.

“Those guys are really very, very, very strong. The French luxury groups, you know, chapeau,” says Gildo Zegna, CEO of the eponymous menswear label founded by his grandfather. “Their firepower … it’s really unbelievable.”

Marco de Benedetti, a scion of one of Italy’s industrialist families who is now a Milan-based partner at the private equity giant Carlyle Group, said French-owned brands simply overwhelm the Italians in the fight for retail space. “You go into a new market. You try to fight to get a little space, and then comes LVMH or Kering, and they say: ‘OK, I take the whole floor’,” he says.

The power imbalance is acutely felt, however, on the catwalk. In June, Louis Vuitton took over the Pont Neuf bridge in the heart of Paris. Not only did Pharrell Williams, the brand’s new creative director for menswear, turn the fabled bridge into a runway for his first collection, he also performed a showstopping duet with Jay-Z. The event quickly garnered more than one billion views on social media, according to the company.

A confluence of forces propelled Italy’s top designers on to the world stage in the ’80s and ’90s. The country had a long tradition of producing high-quality textiles and leather goods – the lifeblood of the luxury industry – at relatively small, family-owned manufacturers.

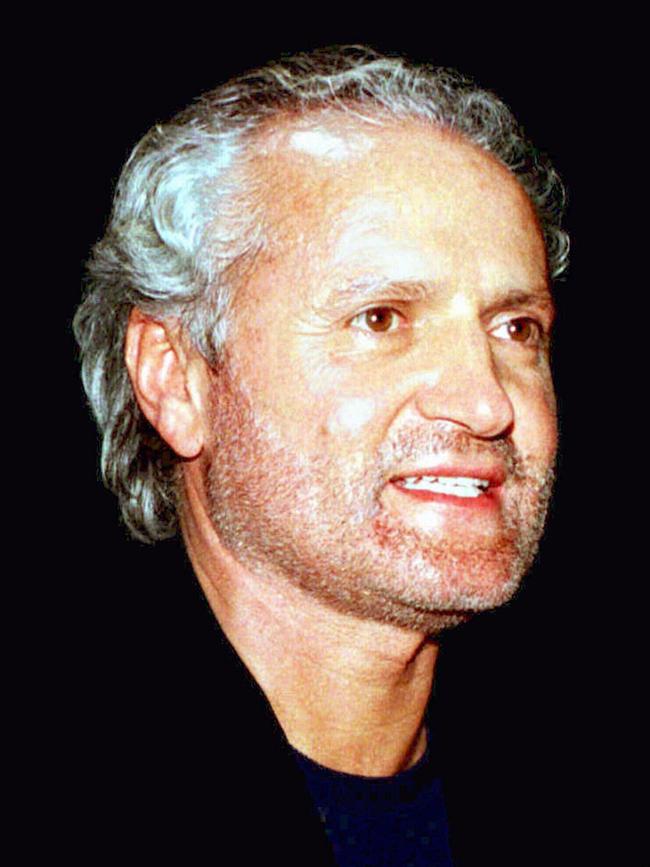

A weak lira helped keep production costs down, and fat profit margins allowed the firms to invest in a generation of emerging designers, such as Armani and Gianni Versace, who launched their own brands.

For global promotion, the designers looked to Hollywood. Dressing a movie star allowed them to punch far above their weight. Armani dressed a young Richard Gere in American Gigolo, a film that catapulted both men to fame. His designs became a mainstay on the red carpet, along with those of Versace.

In the late 1990s, Versace tried to buy Gucci. The combination of two of the industry’s biggest heavyweights would have created a conglomerate to rival LVMH at the time. The plan was ultimately scuttled by the shocking murder of Gianni Versace at his villa in Miami at the age of 50.

In the years that followed, many of Italy’s luxury brands launched initial public offerings in an attempt to raise cash without giving up family control. They have struggled, however, amid investor scrutiny and shifts in the geopolitical landscape.

Prada and Zegna have recently tried to build heft through partnerships. In June, the brands both invested in Luigi Fedeli e Figlio, a storied producer of fine yarns and knitwear based in Monza, north of Milan. In 2021, Zegna and Prada also purchased a majority stake in an Italian producer of cashmere.

“It’s never too late to do things together. And that’s what I’m trying to do with some of my friends in Italy,” says Gildo Zegna.

Still, the list of once prideful Italian brands that have sold out to the French is growing. LVMH now owns Bulgari, Fendi and Loro Piana. Kering owns Bottega Veneta, suitmaker Brioni and jeweller Pomellato in addition to Gucci.

Prada this year put in place a long-awaited succession plan when it tapped a former LVMH executive, Andrea Guerra, as CEO, scaling back the roles of Miuccia Prada and her husband, Patrizio Bertelli, in running the fashion house. Part of Guerra’s job is to groom Lorenzo Bertelli, the couple’s eldest son, to one day take over.

Bertelli isn’t in line to run the creative side of the business – in 2020, Prada tapped 55-year-old Belgian designer Raf Simons to join Miuccia as “co-creative director” – but handing a brand over to the next generation is risky. Too many family members at a fashion house can lead to squabbling. Florence-based Ferragamo, which is run by the third generation, limits the number of family members who can work at the company to three.

Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana said for years that their fashion empire wouldn’t outlive them. “Once we’re dead, we’re dead,” Gabbana told Italian daily newspaper Il Corriere della Sera in April 2018. But in 2019 the duo changed their minds, saying they wanted the Dolce family to take over after them.

Armani’s plans for succession remain fuzzy, at least to the outside world. In 2016, he said he would leave the company to his foundation, but he didn’t say who will run the company or the foundation after him. Armani doesn’t have children. His nieces, Roberta and Silvana, both work at the group while longtime design assistant Pantaleo Dell’Orco heads the men’s lines.

In the northern spring of 2021, Armani suffered a bad fall that fractured his left humerus. The designer was taken to the hospital, where he received 17 stitches.

By June, Armani was back in the spotlight, taking his customary bow at the end of a fashion show. This time, however, the designer took the stage holding the hand of Dell’Orco.

Armani said he was “preparing my future with the people around me”, mentioning his longtime assistant as well as niece Silvana Armani, who heads womenswear.

Since then, Armani has bounced back. Last week he threw a cocktail party on his yacht at the Venice International Film Festival. The next day he hosted a haute-couture show at the Arsenale, the city’s famed shipyards. Another cocktail party followed for hundreds of guests featuring a live performance by Irish-born singer Roisin Murphy and a DJ set by Mark Ronson.

Among those in attendance was Remo Ruffini, CEO and chairman of Moncler, the maker of expensive puffer jackets.

Armani, he said, “was really in good shape, really in very good shape. The face was super. I think he is training a lot. He is paying attention to the food”.

Ruffini didn’t think Armani was bowing out anytime soon, adding: “For me he is the king of Italy.”

The Wall Street Journal