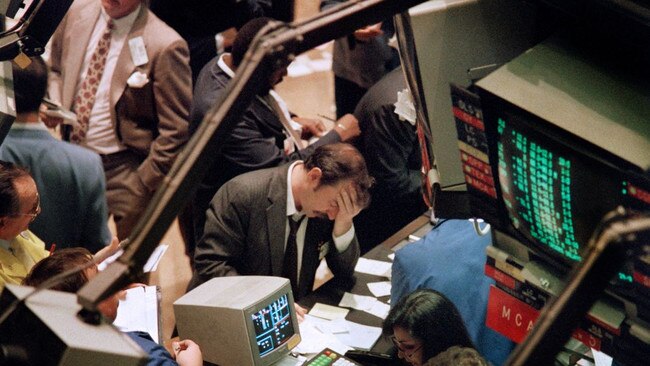

Is this 1987 all over again? What’s driving the market meltdown?

Financial markets are supposed to capture the wisdom of the crowd, but on Monday the crowd ran in all directions waving its hands in the air screaming. One particular data point triggered the panic.

Financial markets are supposed to capture the wisdom of the crowd, but on Monday the crowd ran in all directions waving its hands in the air screaming. Japan’s stock market fell the most in 37 years and the VIX index of implied US stock volatility had the second-biggest rise in data back to 1990. Panic hit.

The sell-off was triggered by Friday’s jobs data prompting a sudden switch in the economic narrative from soft landing to hard landing. Add to the mix a period of deflating hype about artificial intelligence and a Bank of Japan rate rise designed to strengthen the yen. News that Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway had sold half its Apple shares and boosted its cash pile added to the pain.

But the triggers can’t possibly justify the scale of the moves. The sell-off – which at one point had chip maker Nvidia down 15 per cent – was big because investors had been all-in betting that things would work out well. The question is how far the unwind of these bets – and the leverage behind them – will go. If it continues, will the sell-off feed back into higher savings and a weaker economy or, worse, hit the financial system?

The extreme examples of past effects from big market falls are 1987’s crash, 1998’s Long-Term Capital Management blow-up and 2008’s global financial crisis. History is never perfect, but so far this looks more like a (milder) version of 1987 than it does the other two.

In 1987, the stock market had its biggest one-day fall ever, with the S&P 500 down more than 20 per cent on Black Monday in October. Investors had built up excessive leverage after a stunning 39 per cent gain in the year to August’s high, and the crash led both to big margin calls and to badly designed automated trading that exacerbated the selling. But the Federal Reserve poured liquidity into the banks, brokers didn’t default and the market made back all its losses within two years. The economy was fine.

The good news was that 1987 was all about markets: They went up, they went back down, no one else was hurt. The S&P made 36 per cent in the eight months to its August 1987 peak, similar to the 33 per cent it rose in the eight months to this year’s high. As in 1987, this year’s gains came despite tight monetary policy and higher bond yields. Just as today, in 1987 investors were on edge and ready to sell to lock in the unexpected profit. The losses are smaller so far, but lucrative trades have reversed, just as they did for the market as a whole in 1987.

In 1998, the situation was much worse, although stocks recovered more quickly. Highly levered hedge fund LTCM was crushed when Russia’s domestic debt default created a flight to safety. LTCM was big enough that it threatened to bring down Wall Street institutions. The Fed cut rates three times and pulled together a group of banks to rescue the firm and wind down its trades slowly. Stocks took just four months to recover, but the easy money helped stoke the dotcom bubble, which popped two years later and led to a mild recession – and gigantic losses for investors in tech stocks.

We don’t know yet if any hedge funds have been taken out by the big moves in markets, which have brought heavy losses for those engaged in the “carry trade” of borrowing cheaply in yen and buying higher-yielding currencies such as the Mexican peso or dollar. But already traders are betting that the Fed will slash rates, with a super-size cut of 0.5 percentage point priced into futures for the September meeting.

The really bad outcome would be a repeat of 2008, but it seems unlikely. True, some large US banks failed last year, due to bad bets on government bonds. But banks are much less leveraged than they were, and the system is less exposed to a liquidity crisis, as private lenders have taken on much of the risk that used to sit in banks. Big losses are entirely possible, and private funds could hit trouble, but that would take time and wouldn’t create the same system-wide crisis.

The ideal would be that excess in the stock market unwinds as in 1987 without creating wider trouble, hopefully more gradually than in 1987. AI enthusiasm could deflate stock prices much more – even after falling 30 per cent from its June high, Nvidia has still doubled in price this year. But the market is already much closer to normal, with the Nasdaq 100 index up only 6 per cent so far this year, and the S&P less than 9 per cent.

If panic abates, the Fed cuts and nothing breaks in the financial system, we should count ourselves lucky. But it would be good if investors could remember the sinking feeling they had this morning, and try to be a bit wiser and less speculative.

Dow Jones Newswires

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout