Inside Putin’s race to develop a Covid-19 vaccine before the west

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s fast-tracked coronavirus effort has garnered scepticism from scientists and Western politicians.

In April, as Covid-19 cases surged across Russia, President Vladimir Putin called a meeting of the country’s top scientists and health officials over video link to deliver an urgent directive: Do whatever you need to create a national vaccine as soon as possible.

Four weeks later, Alexander Gintsburg, director of the state-run Gamaleya Institute for Epidemiology and Microbiology, told state television that his researchers had developed one. They were so sure it was safe, he said, the researchers had tested it on themselves.

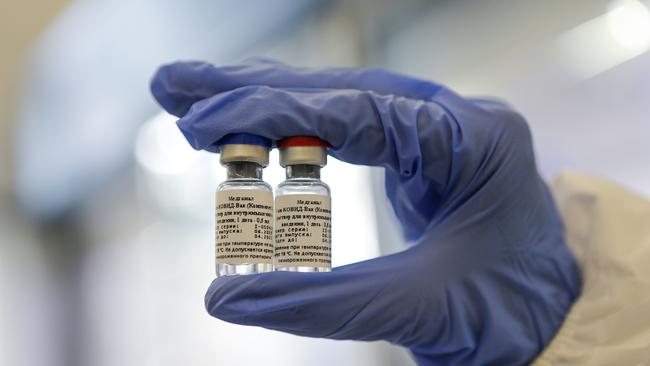

Last month, Mr Putin, with great fanfare, said Russia had approved Gamaleya’s vaccine, making it the first country to sign off on one amid a global race to curb the spread of Covid-19.

Moscow’s self-declared victory has been greeted with scepticism among scientists and Western politicians. Russian researchers have completed only early-stage tests on 76 volunteers and published none of their findings. Large-scale trials on 40,000 volunteers began only last week.

Vadim Tarasov, who oversaw trials of the vaccine at Moscow’s Sechenov University, maintains the shot is safe. “How effective it is, is another question,” he said.

The pressure from Mr Putin for Russia to be first highlights the political victory the Kremlin is seeking to score by pushing its best scientists into the centre of the global fight against the coronavirus.

Russia was racing to catch up with efforts in China and the West, calling its vaccine Sputnik V, a reference to the satellite it launched into orbit ahead of the US in the Cold War space race. A shot co-developed by AstraZeneca PLC and the University of Oxford, as well as vaccines from Moderna Inc. and Pfizer Inc., have already been in late-stage, or Phase 3, clinical trials, as were candidates from Chinese drugmakers Sinovac Biotech Ltd. and China National Biotec Group Co.

“Even the name tells you that the whole point of this is to get geopolitical advantage, to be the first,” said Konstantin Chumakov, a US-based Russian virologist and member of the Global Virus Network, an international scientific collaboration.

“It might be a great vaccine. But we just don’t know,” he said. “It’s a gamble with people’s lives, a Russian roulette.” Others have also sought to move ahead before all trials have been completed. China’s CanSino Biologics Inc. is in talks with several countries to secure emergency approval for the use of an experimental vaccine it developed with the Chinese military before the completion of large-scale trials, according to a senior executive at the company.

In addition, President Trump has complained that regulatory procedures have slowed down ahead of the coming presidential election.

The fast-tracking of Sputnik after Mr Putin’s intervention underscores a distinctly Russian approach toward medicine. Observers say it isn’t uncommon for a top-down directive to take precedence over rigorous scientific protocols.

Russian scientists involved in the vaccine effort say that their work isn’t done. The vaccine’s registration, they say, is conditional and more evidence will be needed before it is rolled out to the public. And it could be withdrawn from the market if proven to be unsafe or ineffective, health officials said.

Still, said Mr Tarasov, who is director of Sechenov University’s Institute for Translational Medicine and Biotechnology, “If there’s a new wave in the fall, we have a safe tool we can use.” When Russia reported its first cases of Covid-19 in two Chinese citizens living in Siberia on Jan. 31, the news sparked panic in Moscow. Scientists quickly sought to understand as much as they could about the virus.

Working for weeks with information Chinese scientists had put online, researchers at the Gamaleya Institute drew comparisons with a different coronavirus strain, Middle East respiratory syndrome. The institute was already in the process of making a vaccine for MERS, Mr Gintsburg said.

By using a formula similar to the one they had developed for MERS — and before that against Ebola — scientists had a jump start. Gamaleya received its first synthesised gene of the novel coronavirus in late February. About a week later, it had its vaccine ready, Mr Gintsburg said.

The vaccine uses a method developed since the 1950s to create what is known as adenovirus vector vaccines. That kind of shot uses a genetically altered form of a harmless virus that causes the common cold, known as the adenovirus, to serve as a vehicle for a fragment of genetic material from the new virus. This genetic material, a so-called S protein, is safe for the body but still helps the immune system to react and produce antibodies, which protect it from an infection.

Gamaleya’s team of around 100 people worked nearly non-stop, drawing their shades in the lab to block out sunlight as they tested their vaccine on rats and rabbits.

Mr Gintsburg’s scientists weren’t alone. In labs from St. Petersburg to Siberia, researchers in white coats and rubber gloves worked in restricted labs day and night, hunched over vials and syringes, working on a total of 47 vaccine candidates. Scientists worked on a number of vaccine variations, including one that could be administered in yoghurt.

But Russia was already late to the show. As Gamaleya’s scientists were only starting to test on mice and rabbits at the end of March, researchers in Oxford, England, and Cambridge, Mass., were already working with human volunteers.

In the weeks that followed, Gamaleya researchers moved on to primates, and by April the first researchers had injected the vaccine in themselves. In mid-June, they started formal human test trials, and through the ministry of defence, Gamaleya administered the shot to 38 Russian contract soldiers.

Russian scientists take pride in their well-established school of vaccine development, dating back to Catherine the Great, who was inoculated against smallpox in the 18th century. In a rare collaboration during the Cold War, vaccines developed by US and Soviet scientists helped mostly eliminate polio and smallpox around the world. The nearly 130-year-old Gamaleya Institute has its own vaccine production facility and runs a large virus library, collecting strains from around the world.

As Russia’s coronavirus caseload grew, the pandemic itself became a stumbling block for researchers. Mr Tarasov’s lab, which was testing the Gamaleya vaccine, had to find a new home after its space inside the university was transformed into a coronavirus ward. Some of the experts working on the vaccine were drafted to help with patients, dividing their time between treating infections and the research needed to prevent them.

Meanwhile, researchers advertised for civilian volunteers. Moscow entrepreneur Georgi Smirnov was isolated twice.

The 23-year-old first spent two weeks at a renovated Soviet-era sanatorium outside Moscow to make sure he and other volunteers weren’t infected. In July, he was transported to a Moscow hospital, where doctors injected him, along with 37 others, with Gamaleya’s vaccine. For the next four weeks, his only direct contact was with researchers in protective gear who brought him food, measured his temperature and took saliva swabs.

The volunteers were paid $1,300 and Mr Smirnov said he used the money to help pay for his sister’s education.

After receiving the jab, Mr Smirnov, a former army man and gym enthusiast whose latest hobby is skydiving, said he had a slight headache and higher temperature but the symptoms dissipated quickly and he had since been feeling fine. Mr Tarasov said these were standard reactions for all vaccines.

As Russia sped toward approving the vaccine in August, Russia’s Association of Clinical Trials Organisations, a nongovernmental organisation for global pharmaceutical companies, wrote an open letter to the health ministry asking it to delay registration of the vaccine until all clinical trials were completed.

There are questions over whether the vaccine is strong enough to impart long-term immunity or how patients with chronic health problems would respond. One fear is that it could give people the wrong kind of immunity, which can end up enhancing the disease rather than protecting against subsequent infections, a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement, said Anna Durbin, professor of international health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Likewise, giving people confidence to leave their homes and eschew lockdown measures without providing full immunity could cause the disease to spread even faster.

US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in August that it was more important to have a safe and effective vaccine against the coronavirus than to be the first to produce one.

Russian officials say detailed information on the immunity the vaccine imparts will only be available after the large-scale phase of testing, which they say could take four to six months.

Last month, Mr Putin, who has said his own daughter has taken the vaccine, publicly said the shot had proven effective at creating antibodies, though he presented no evidence.

“Our specialists are absolutely confident today that this vaccine creates lasting immunity and people get antibodies, as was the case with my daughter,” he said in a televised interview last week.

He said that a second Russian vaccine would be registered in September. Countries are already lining up for Russia’s first vaccine. Moscow is in talks with more than 20 nations in Asia, South America and the Middle East to export the shot.

Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout