In the world’s coronavirus blind spot, fears of a silent epidemic

In Africa, limited testing and spikes in respiratory illnesses raise concerns that coronavirus could be spreading unnoticed.

The global scramble to thwart the coronavirus has a vast blind spot: sub-Saharan Africa.

In Tanzania, the government outlawed coronavirus testing and declared its national outbreak defeated, even as hundreds of people died monthly from unexplained respiratory problems. Last month in Zambia, 28 people died at home in a single day with COVID-19-like symptoms while waiting to be tested. In South Sudan, government forces barricaded thousands of people inside refugee camps, claiming they were infected but refusing to test them.

A lack of testing capacity, limited access to data and secretive governments across Africa have made it appear as if many of the world’s most impoverished economies have avoided the worst effects of a disease that has killed at least 845,000 people worldwide. But the plight of many of sub-Saharan Africa’s one billion people is effectively invisible to global authorities trying to gauge the severity of the pandemic.

The paucity of data — combined with reports from several nations of spikes in deaths from respiratory illnesses — is raising fears that a silent epidemic could be raging in parts of the continent. Official coronavirus cases in sub-Saharan Africa have doubled in the past month to more than one million, but the official death rate — at 20,000 — remains significantly lower than those of less-populous Europe and the US, according to World Health Organisation data.

The World Bank says these unknowns could prevent African economies from reopening fully for years, aggravating an economic emergency the UN has warned is already pushing tens of millions of people into hunger and shrinking the continent’s newly minted middle class. The risk is compounded by fears that African countries may be forced to wait for COVID-19 vaccines given production constraints and the scramble among wealthier countries to secure supplies.

“We are fighting this disease in the dark,” said Stacey Mearns, senior technical adviser of emergency health at the International Rescue Committee. “The world doesn’t really know the scale of the disease on the continent.”

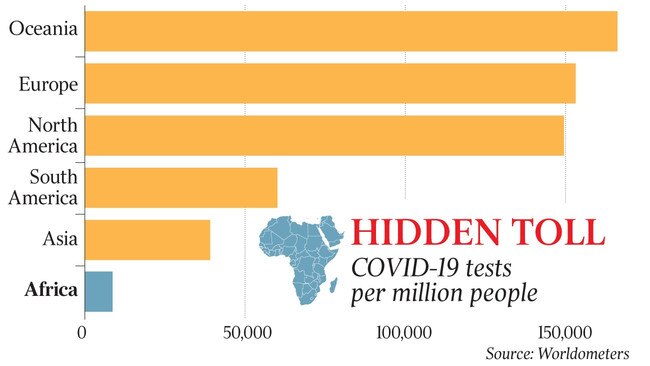

Data on the virus’s spread across Africa is woefully limited. Sub-Saharan Africa’s 46 nations have conducted 6.3 million coronavirus tests for a population of one billion, significantly fewer than the number in the state of New York, which has 8.3 million people.

African nations average about 5000 tests per one million people, according to data from the African Union, compared with nearly 500,000 tests per one million in the United Arab Emirates and 200,000 in the US. Three-quarters of tests in sub-Saharan Africa have been conducted by four nations — South Africa, Kenya, Ghana and Ethiopia — meaning that data from the rest of the continent is perilously scarce.

“There is a significant undercount of coronavirus cases in Africa due to insufficient testing,” said Farouk Umaru, director of global public health laboratory programs at Pharmacopoeia, a Washington-based non-governmental organisation that advises the US government on medical standards and licensing.

“Rapid scale-up of diagnostic testing is critical in response efforts to contain the pandemic.”

The most granular data and proactive efforts to contain the virus on the continent have come from a handful of democratic governments that have mobilised public and private sectors to give a clearer sense of trends.

South Africa has conducted more than 3.5 million COVID-19 tests for its 60 million people. Trials to develop a $1 testing kit that produces results in fewer than 10 minutes are under way in Ghana and Senegal, which have used 3D printers to produce ventilators.

But across swathes of the continent, the true scale of the virus is unknown. South Sudan has tested 15,000 of its 12 million people. Several countries, including Niger, Eritrea and Guinea, have each carried out fewer than 10,000 tests. Tanzania has conducted the fewest tests in the world, according to the World Health Organisation, at 63 per one million people, before it stopped providing international bodies with test data.

When the first suspected cases of the coronavirus started cropping up in Africa in early February, only two laboratories — one in South Africa and the other in Senegal — had the diagnostic capacity to test for the virus. It took nearly two months for all 46 nations south of the Sahara to put in place some testing capacity.

Some countries have gone to great lengths to ensure information testing isn’t shared. The government of Equatorial Guinea expelled WHO representatives, accusing them of falsifying new virus cases after announcing its outbreak was over. When Burundi’s President, Pierre Nkurunziza, died in June at the age of 55 his autocratic government said the cause was a heart attack, but diplomats and medical professionals believe he was the world’s first head of state to die from COVID-19.

Tanzanian authorities closed a local newspaper after it published a picture of President John Magufuli at a crowded fish market in April in violation of social-distancing rules announced by his government. Another local TV station had its licence suspended in July after it reported an alert from the US embassy warning of an elevated coronavirus risk in the country. A law introduced last month prohibits citizens from discussing infectious diseases online without government approval, and dozens of Tanzanians, including prominent government critics, have been arrested for commenting on the virus on social media.

“Posting information about the coronavirus pandemic is now considered unpatriotic,” said Muthoki Mumo, sub-Saharan Africa director at the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Zambia began testing by late February, but the heavily indebted nation has struggled to expand its facilities, according to interviews with Zambian officials and health experts. The country of 18 million has conducted 100,000 tests, but pleas from the Treasury, which spends one third of its revenue servicing debt, to lenders including China and the International Monetary Fund for emergency funding have largely been rebuffed amid disputes over the country’s debt load.

The economic chaos is visible in hospital wards across Zambia. Coronavirus testing capacity is so limited that people with respiratory symptoms often spend days searching for hospitals that have testing kits before they can be treated. Dozens have died waiting to be tested and others have died before receiving test results, potentially spreading the disease to relatives, medical officials say.

“We have limited supply for testing owing to the global shortage,” said Kakulubelwa Mulalelo, the permanent secretary at Zambia’s health ministry. “Testing is conducted at the discretion of health officials.”

The chances of surviving coronavirus for patients with pre-existing medical conditions are significantly lower, and many families in Zambia have talked of losing close relatives already sickened by diseases such as diabetes and HIV-AIDS.

Unable to find hospital beds for sick relatives, some residents such as Moreen Shabusale, a Zambian hairdresser, have resorted to stocking antibiotics, hydroxychloroquine and painkillers. Ms Shabusale’s 52-year-old brother died earlier this month, three days after he had been told to wait for the arrival of coronavirus testing kits at a local hospital. A 21-year-old relative was recently battling high fever, coughing and night sweats.

“They are not admitting any patients to a COVID-19 ward without test results, but they turn people away without treatment,” she said. “It’s pathetic.”

The situation is even less clear in Somalia, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where raging insurgencies mean mass testing is impossible and weak healthcare systems are already struggling to contain other medical emergencies including HIV-AIDS, measles and Ebola.

The dearth of tests goes beyond limited state capacity. Stigmas about COVID-19 are preventing people from getting tested, health officials say. In Somalia, the number of people seeking treatment at health facilities has dropped by a third since March, according to Care International, an NGO, as more people suspected of being infected are cut off from communities.

Shabir Madhi, a professor of vaccinology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, said the testing figures across Africa were so incomplete they were meaningless.

“It doesn’t quantify the true magnitude of circulation of the virus,” he said.

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout