If Tesla bubble bursts, catastrophe won’t follow

Not all bubbles are equal. Britain’s bicycle-stock bubble of the 1890s holds lessons for today’s electric-vehicle mania.

Recent experience and financial lore have created the impression that the bursting of market bubbles brings economic destruction. But it isn’t always so. The excess in today’s story stocks– electric cars, clean power and cannabis in particular– surely poses a threat to the wealth of their shareholders. Even if there is a wider bubble, it might not be a catastrophe for the country.

The experience of the past few decades suggests the opposite. Japan is still scarred by the 1980s property and stock bubble, the dotcom bubble led to massive losses and the subprime crash created a global crisis.

But not all bubbles are equal. The economic dangers of a stock bubble come from people taking on debt to buy shares and from companies overinvesting. When the bubble pops, overextended shareholders have to cut spending or go bankrupt. Companies suddenly faced with investors demanding a return have to lay off workers and slash investment.

None of this is an issue for the obvious bubbles under way in the fashionable stocks of the moment. Tesla is valued so highly it is now the U.S.’s fifth-biggest company by market capitalisation. Even if the electric-car maker vanished tomorrow, it would have an insignificant effect on the economy, as Tesla’s operations are tiny. It is mostly equity-financed, so its failure wouldn’t start a domino line of bank failures. And while shareholders would be hurt, there’s no reason to think that would lead to a collapse in spending across the country.

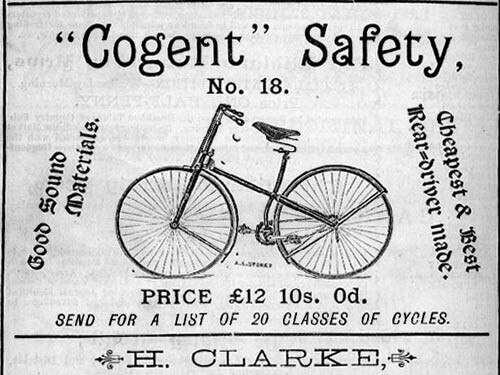

The closest parallel is not the dotcom bubble, for all the similarities, but the British bicycle mania of the 1890s. Bicycles were the electric cars of their day: breakthroughs in tire and gear technology made them into convenient and environmentally friendly transport, albeit still expensive. Investors rushed in and stock promoters spotted the opportunity to float any company with a connection to the industry, mostly in Birmingham. Heavy investment led to further breakthroughs; and, at the peak, bicycle-related patents made up 15% of all the patents issued.

Bicycle stocks were helped by what was then the lowest yield ever on U.K. government bonds, which encouraged further mini-bubbles in Australian mining and breweries.

In their book “Boom and Bust,” academics William Quinn and John Turner from Queen’s University, Belfast, document 671 new bicycle companies, raising £27 million in 1896 alone– equivalent to 1.6% of British gross domestic product that year. By comparison, the fast-growing IPO alternative of SPACs raised about 0.4% of US. GDP last year and are running at an annual rate of about 1.3% so far this year.

Half the bicycle companies that joined the market failed by the end of the decade. The speculators who held when the bubble burst were hit by a 71% fall in bicycle stocks from their peak in just 18 months.

The regional economy suffered when the stocks collapsed, but Britain as a whole barely noticed, and the rest of the market wasn’t much affected.

What if today’s excesses aren’t just in the speculative story stocks like Tesla, but across the market? I don’t think Big Tech-including Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook– is a bubble, because high valuations can be broadly justified by very low Treasury yields. But if I’m wrong and shares in the highly valued technology and associated sectors did crash, it probably wouldn’t be that bad.

Sure, investors – that’s you and me -would lose money. But with a few exceptions these companies aren’t borrowing or issuing new stock to fund new investments, and their investors aren’t all that leveraged. If Apple’s share price halved, it would make no difference to the underlying business. That is different from the dotcoms, which were forced to slash spending when the market crashed, and they lost the ability to issue expensive new shares.

“The historical lesson is that stock market crashes don’t really cause that much damage,” Mr. Quinn says. “Bubbles funded by banks were the really really destructive ones.” Black Monday in 1987 is a classic example: harrowing for shareholders, but irrelevant to the economy.

Of course, we shouldn’t be too confident that everything will be fine. So let’s go through the risks.

Unlike past episodes, the Federal Reserve can’t help out so easily now. Rates are already on the floor. After the broader market fell six months after the dot.com bubble burst the Fed rapidly cut rates from 6.5% to 1.75%, and eventually 1%, helping protect the economy from the market decline.

Corporate debt is also exceptionally high. Weaker companies have borrowed to survive the pandemic lockdowns, while stronger companies have borrowed to buy back stock. Lower rates mean debt is more affordable than ever before, but if markets lose confidence it could be harder and more expensive to refinance.

Big falls in stocks can feed through to the economy by making people feel poorer– and so spend less.

Finally, sentiment is vital. Most workers wouldn’t be affected directly by a big fall in stocks, because relatively few people own shares, even after last year’s boom in trading. But with stock prices closely followed in the media and by companies, a crash could create a mood of national gloom, with knock-on effects on corporate and consumer confidence that in turn hit spending.

I’m not too worried about these risks because I think there’s only a relatively small set of bubble stocks, and they can burst without serious damage. If I’m wrong and it turns out there’s a bigger bubble– after all, almost everything is very expensive compared with the past– then I would be more worried. But the economy would probably still be fine, and surely better off than when banks were financing a housing bubble.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout