How the Ukraine war changed history

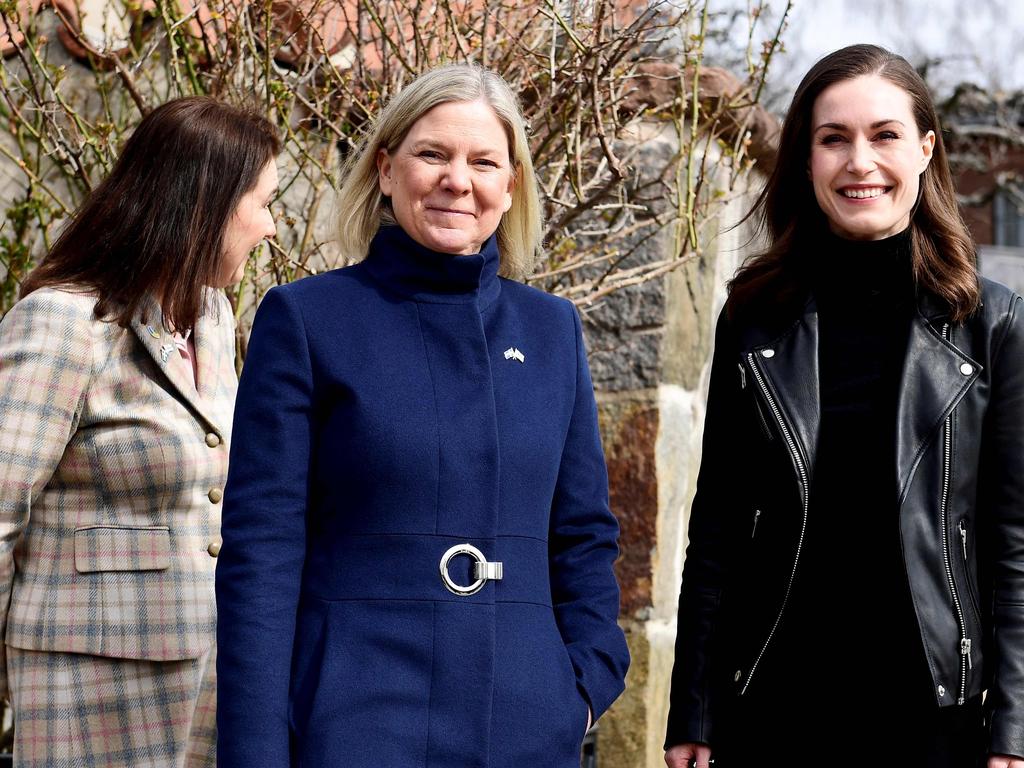

We do not know how the war in Ukraine will end, but it is already evident that it represents a turning point in contemporary history. To begin with, the war has ended the debate about the purpose of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the possibility of its expansion. Strategists who feared that extending its protective umbrella to Central Europe and the Baltics would provoke Russia acknowledge that the invasion makes further expansion inevitable. Finland and Sweden, which previously shied away from a formal relationship with the alliance, appear on the verge of applying for membership. Emmanuel Macron, recently re-elected as France’s president, is unlikely to renew his oft-repeated charge that NATO is “brain dead”.

Instead, NATO will emerge from the war in Ukraine as a more united and effective defensive force. As members transfer their stocks of Soviet-era weapons to Volodymyr Zelensky’s government, the US and others will replace those stocks with modern weapons that can operate in tandem across the alliance.Second, the war has transformed Germany. Europe’s economic powerhouse has abandoned a foreign and defence policy shaped by memories of World War II and has pledged to rebuild its military and expand its military spending to at least 2 per cent of gross domestic product. Step by step, it has relaxed prior limits on arms transfers to countries actively engaged in military conflicts and recently agreed to send heavy weapons to Ukraine.

Third, the war is forcing Europe to reduce its dependence on Russian energy. In an era of tight supplies and high prices, this will be painful. But even Germany, whose extensive energy ties with Russia have long been a strategic weakness for the West, realises there is no alternative.Although former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to phase out German nuclear power was ill-considered, technological and political considerations will make it hard to reverse. Even France, which has made a long-term commitment to nuclear power, is finding it difficult to build new capacity without long delays and soaring costs.

Over the next decade, Europe must accelerate its transition to renewable energy sources while replacing Russian fossil fuels with supplies from the Middle East, Africa, and the US. Among other measures, this necessitates a crash program to build the facilities European ports will need to receive large shipments of liquid natural gas. It will require the West to pay more attention to political stability and economic conditions in Nigeria and other African countries. And it means that the US. must assist Europe with an energy policy that balances long-term concerns about climate change with the fossil-fuel supplies that Europe will need to weather a difficult decade of transition.The war in Ukraine has strengthened some ways of thinking about geopolitics while weakening others. For example, it is no longer possible to believe, as many did before World War I and again after the collapse of the Soviet Union, that economic considerations dominate politics and make some measures unthinkable.

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine will trigger a sharp recession and could lead to a long-term decline in Russian living standards. Elvira Nabiullina, the respected head of Russia’s central bank and a Putin loyalist, understood this and tried to resign in protest, but Mr. Putin was unmoved. The desire to eliminate a perceived threat to his legitimacy and realise his dream of re-creating the Russian empire took priority.The Russian president’s fateful decision dealt a body-blow to conservative populists throughout the West who saw him as a champion of traditional values concerning gender, family, religion and nationalism. Even Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has been forced to tone down his pro-Russian rhetoric. In the U.S., Trump supporters have joined Democrats and non-Trumpist Republicans to condemn the Russian invasion and back tough American measures against it. Mr Putin’s aggression has done more to unify public opinion in the US. than any other event since 9/11.

Finally, the Russian invasion has forced the US to shift its focus from facing transnational threats to winning a great-power competition. Yes, important issues such as global health and poverty, immigration flows triggered by conflict and privation, and climate change remain on the agenda. But for the foreseeable future, challenges from Russia and China will take centre stage.

With this shift also has come a renewed recognition of the importance of hard power. To be sure, words can make a big difference. The Biden administration’s decision to undermine potential Russian false-flag operations by making intelligence findings public was a masterstroke. But Ukraine’s president, who has used speech to rally his country and the world, insists that without huge inflows of weapons, the battle to defend his country will fail.

The question is whether US President Joe Biden will draw the obvious conclusion. If the US must defend democracy against autocracy, as Biden rightly insists it must, it will need to devote more than 3 per cent of its GDP to defence — and reorder military spending to counter today’s threats on the European and Asia-Pacific fronts.

The Wall Street Journal