How museums aim to stop food-throwing, climate-change protesters

After months of watching climate protesters slather famous paintings in tomato soup or mashed potatoes, stunned museums are fighting back.

Museums are enacting “zero bag” policies, putting prized paintings behind glass and hiring ex-British and Israeli military pros to teach their guards surveillance tactics after a series of climate-change protests have left the world’s most famous art slathered in mashed potatoes and tomato or pea soup.

“Museums have always been aware of people trying to steal their art,” said Remigiusz Plath, head of infrastructure and security for Germany’s Hasso Plattner Foundation, whose Claude Monet Grainstacks recently was doused in mashed potatoes at Potsdam’s Barberini Museum. Glass helped protect the Monet. But as to warding off grocery-wielding vandals who claim they don’t want to damage the art, he said: “That threat is definitely new.”

A week ago, Germany’s Last Generation activists were back at it, sloshing pea soup on Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 The Sower at Rome’s Palazzo Bonaparte. Paris’s Orsay Museum said it foiled an attempt days before by a Just Stop Oil activist to throw soup on one of its paintings.

Both canvases were protected behind glass, but museums say they are getting fed up. Amotz Brandes, a former member of the Israeli military, said museums were enlisting his security consulting and training firm to learn counter-manoeuvres. One tactic he suggests: watch for visitors who show up solo yet start communicating with others once inside using non-verbal gestures, like pointing. “It’s all about early detection,” Brandes said.

One of the art world’s strangest showdowns is pitting museums against environment activists who in recent months have smuggled in and tossed all sorts of foodstuffs on to some of the world’s most famous artworks. Protesters say such actions draw attention to the doomsday effects of climate change. Curators complain the world’s masterpieces are being endangered as political pawns.

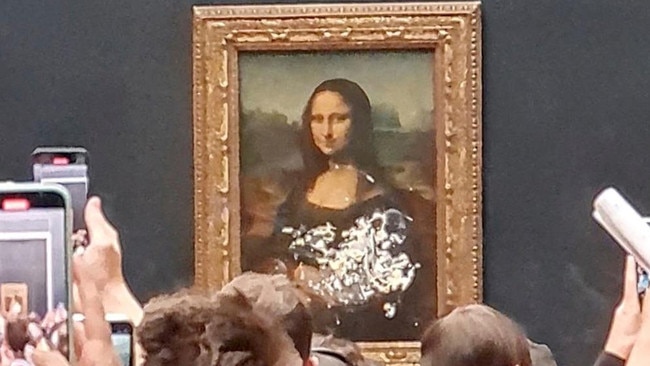

Activists have long come to museums to advocate for everything from women’s voting rights to nuclear disarmament, sometimes violently. In 1914, suffragette Mary Richardson used a meat cleaver to hack into Diego Velázquez’s Venus at Her Mirror at London’s National Gallery. The Louvre Museum’s Mona Lisa weathered red spray paint and an acid-throwing attempt decades before May this year, when a man disguised as an old woman smeared cake frosting on the glass covering Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait, telling onlookers to think of the planet’s welfare.

Last month a man and a woman were arrested after they glued themselves to Picasso’s Massacre in Korea at the National Gallery of Victoria, temporarily closing the exhibition. Last week protesters scrawled across Andy Warhol’s modernist classic image of Campbell’s soup cans at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

In May 1972, unemployed Australian geologist Laszlo Toth attacked Michelangelo’s $450m Pieta at St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, smashing it with a hammer.

Today’s protesters vow that they don’t want to harm the art, but the latest round of vandalism comes as museums are already struggling to rebuild their coffers, staffing and attendance levels since the pandemic. Redoubling security measures now could prove too costly.

Robert Wittman, a former art-crime investigator at the Federal Bureau of Investigation who said he keeps in touch with museum security personnel, said most museums can’t stretch their budgets to quickly hire more guards or install noticeable security measures like metal detectors, which wouldn’t detect food, anyway.

In Europe, where the food-related attacks have so far taken place, Wittman said guards rarely even check visitors’ bags. Food is often allowed on museum grounds so visitors can have picnics.

Plath agreed, saying the “zero bag” policy and mandatory coat checks he instituted last week at the Barberini after the Monet incident remained largely “unheard of” elsewhere.

For now, more museums are turning to the kinds of security consulting firms that typically work with major sporting venues or airports to teach their museum guards ways to spot suspicious activity.

Brandes said he’s tested more than a dozen museums by sending in what he calls “red teams”, or role-playing protesters, to mill around galleries scouring for security cameras, he said, or head straight to a famous painting and then leave rather than strolling around afterwards like a regular tourist might. He coaches museum guards to eye such activities more closely.

Andy Davis, managing director of a UK-based security consulting firm, said such proactive protocols remained “patchy” at smaller museums, where security may be overseen by an administrator with retail experience, not law enforcement. “Everyone wants to think it won’t happen to them,” Davis said.

Security firms say the Louvre is widely hailed for having Europe’s toughest museum security protocols including bag checks, but its guards still weren’t able to stop the cake-smearing man in May, and incidents have accelerated since.

In August, protesters used glue to affix themselves to treasures including the Vatican’s marble Laocoön and His Sons. Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers was hit with tomato soup on October 14. (The painting was protected behind glass, but its frame was slightly damaged.) A week later a man tried gluing his own head to the glass covering Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring at the same time as a peer poured soup on him at The Hague’s Mauritshuis. The dinosaur displays at Berlin’s Natural History Museum were targeted on October 30.

“Art is defenceless,” the Mauritshuis said after the Vermeer dousing.

Each of these incidents has sparked a social-media uproar. After Sunflowers was souped, rapper Lil Nas X responded with an Instagram meme in which he appeared to throw an image of the painting on to an Andy Warhol silk-screen of a tomato-soup can. In the caption, the rapper said he was avenging van Gogh.

Heavyweights like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York or the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles aren’t divulging their battle plans for fear of putting their art under an unwanted spotlight — but curators and environmental activists agree that major museums will be targeted, eventually. Hollywood is already playing a role in funding the climate activist groups behind the global food fight. Arguably the highest-profile entity donating millions of dollars to protesters now is Beverly Hills’ Climate Emergency Fund, an umbrella-like fundraising non-profit supported by Don’t Look Up director Adam McKay and co-founded in 2019 by Aileen Getty, a philanthropist and granddaughter of oil tycoon J. Paul Getty.

McKay declined through his publicist to comment, but when he joined the fund’s board in September he said he admired its “civil, nonviolent, disruptive activism”. The climate fund confirmed the director had donated $1.5m and pledged another $4.5m to the fund.

Getty, in an email, said she had no say or sway over the groups’ disruptions but only allows the fund’s moneys to be used for legal activities. She confirmed that her namesake foundation initially gave $1.5m to co-found the climate fund, which in the past year has given out $6.7m to 43 activist groups such as Just Stop Oil.

She said the climate fund’s money could be used to help recruit and train protesters but could not be used to pay for any illegal, food-throwing activities.

The fund said its donations also could not be used to cover any legal bills for protesters after museum incidents, including the two protesters in the Sunflowers case who were later charged with causing criminal damage. A Just Stop Oil spokesperson said the pair had not hurt the art; they pleaded not guilty.

Getty, a self-taught artist whose grandfather founded the Getty museum, said it mattered to her that protesters were intentionally targeting pieces behind glass, lessening the risk of causing any lasting damage.

“These actions have struck a nerve in society by targeting something beautiful that we love,” she said. “The risk of such an action is turning off people who support the message but not the tactic.”

Even so, she said: “This is not about attacking art. This is about sounding the alarm to protect life on this planet.”

Philadelphia paintings conservator Steven Erisoty said art behind glass could still be damaged, particularly if canvases sat in century-old frames outfitted with felt-covered wood or plastic spacers or other elements that may hold an artwork still – but rarely vacuum-seal it.

But it’s the glue being used in some protests that spooks Erisoty. One slip-up involving a painting not behind glass, and “that’s the nightmare scenario,” he said.

Plath said he was rushing to put more of the Barberini’s pieces behind glass in part because he thought activists would take increasingly drastic measures to stay in the public eye, adding: “It’s the escalation that worries me.”

Margaret Klein Salamon, the climate fund’s executive director, said activists weren’t trying to drive museums crazy. Earlier actions such as gluing themselves to fuel tankers or protesting in front of oil terminals just never captured the same amount of attention. “Frankly, this is the thing that’s worked,” she said.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout