How months of geopolitical upheaval paved way for Gaza cease-fire

The broad terms of the deal between Israel and Hamas aren’t substantially different from those that were available to both sides eight months ago. What changed is everything else.

The broad terms of the cease-fire deal that Israel and Hamas finally agreed to Wednesday after a year of fruitless negotiations aren’t substantially different from those that were available to both sides eight months ago. What changed is everything else.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spent the first half of last year fighting with political rivals and trying to keep his governing coalition together. He was stuck in a war of attrition with Hamas in Gaza and facing ominous threats from Iran and its allied militia in Lebanon, Hezbollah.

Then the tables turned. Israel killed Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar in Gaza and battered Hezbollah with a series of operations that pushed the group to accede to a cease-fire in Lebanon. A strike on Iran destroyed most of the country’s air defenses. The Assad regime collapsed in Syria, punching a bigger hole in Iran’s network of militias. As prominent Palestinians began calling for an alternative government for the Gaza Strip, Netanyahu shored up his political base at home.

Meanwhile, both sides have been galvanized by President-elect Donald Trump’s imminent return to office. The incoming president said a week ago that “all hell will break out in the Middle East” if the hostages held in Gaza aren’t released by the time he is inaugurated on Jan. 20. He hasn’t explained what he meant, but last week said it wouldn’t be good for Hamas or “frankly, for anyone.” The result is a deal agreed to by Israel and Hamas that will pause their fighting in the Gaza Strip and open a pathway to end a 15-month war that has devastated the enclave and sparked wider conflict in the region.

The cease-fire, agreed to during talks in the Qatari capital Doha this week -- though Netanyahu said there are still clauses to be finalized -- would be implemented in phases beginning with an exchange of hostages for Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails, and moving on to talks over a broader end to the fighting. Those latter talks will likely be contentious, as Israel and Hamas remain at odds over whether there should be a permanent halt to the fighting.

“U.S. pressure, coming from President Trump directly, I think has been a huge motivator, particularly on Prime Minister Netanyahu,” said Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Chatham House, a think tank in London. “But this deal is very fragile.” Far-right members of Netanyahu’s government have publicly denounced the agreement, which they say will end Israel’s war in Gaza without uprooting Hamas. But in recent days Netanyahu has made headway toward shoring up support for the deal within his government, even without far-right votes, according to people familiar with the matter.

Netanyahu has repeatedly said that he has worked toward a cease-fire. Nevertheless, for months he has faced allegations from within his own security establishment of slow-walking a deal to avoid making choices that would potentially anger his right-wing partners and derail his political career.

Since September, however, Israel’s series of military successes strengthened Netanyahu politically. The prime minister’s office said ahead of the cease-fire deal it was those achievements during the war, and pressure brought by the U.S. president-elect, that ultimately forced Hamas into a truce.

The Israeli public broadly supports a deal, with 60% saying they believed Israel achieved its military objectives in Gaza and should focus on diplomatic efforts to release the hostages, according to a survey this week by Agam Labs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“Netanyahu has basically come to the conclusion that he can make this deal, stay in power and get credit to some extent for getting the hostages back,” said Gadi Wolfsfeld, a political scientist at Israel’s Reichman University.

The fighting in Gaza was triggered by the Hamas-led Oct. 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel, which left around 1,200 dead and some 250 people taken hostage. More than 46,000 people have been killed in Gaza, according to Palestinian health authorities, who don’t say how many were combatants.

Israel says 94 hostages taken during the Oct. 7 attacks remain in Gaza, most of them Israeli. They include dual nationals and more than 30 hostages who Israel has concluded are no longer alive, based on intelligence findings. Israeli and U.S. officials privately believe the number of dead is much higher.

For Hamas, the turning point toward a cease-fire came in October when Israel killed Sinwar, Hamas’s leader and the architect of the attacks that sparked the war. Sinwar had consistently pushed Hamas to agree to a deal that ensured a permanent end to fighting and the U.S.-designated terrorist’s survival.

Even until recently, Hamas under the leadership of Sinwar’s younger brother, Mohammed Sinwar, was taking a hard line on talks and recruiting new members to continue the fight.

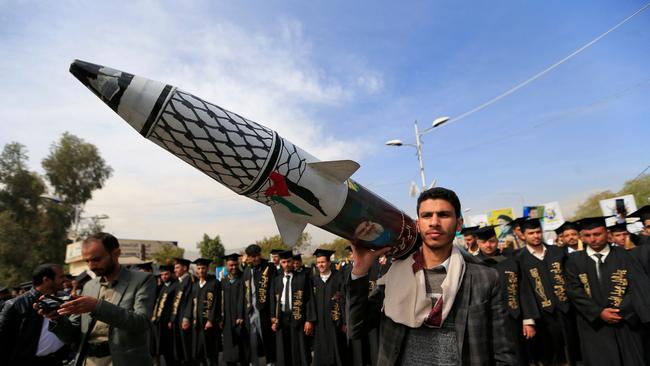

But the group has been battered. Before the war, Israel believed that Hamas had up to 30,000 fighters arranged into 24 battalions in a structure that loosely resembled a state military. The Israeli military now says it has destroyed that organized structure and has killed about 17,000 fighters and detained thousands of others. The militant group hasn’t said how many of its fighters have been killed.

Hamas also has faced growing internal pressure to end the war from Gaza residents who have endured widespread destruction, death, displacement and the breakdown in law and order. People have been angry for months about false starts in the cease-fire talks. On social media, Palestinians in Gaza had urged Hamas to accept a deal even if it meant giving up on some of its demands.

Community leaders, business people and the heads of prominent families made a number of appeals in recent weeks for the Palestinian Authority -- which governs much of the West Bank and had run the Gaza Strip until being forced out by Hamas in 2007 -- to take over the enclave again.

“Hamas’s bets during the war were misplaced,” said London-based political analyst Akram Atallah, who signed one of the appeals. “It seemingly did not anticipate Israel’s severe response or realize that the hostages it holds would not serve as a strong bargaining chip. Israel views this as an existential war.” The worsening situation forced Hamas into the most serious negotiations in months. When the deal was announced, Palestinians in Gaza celebrated in the streets, and cheerful comments filled social media.

The first stage of the deal would pause fighting in Gaza and allow for the release of some Palestinian prisoners held in Israel, in exchange for the release of 33 hostages being held in Gaza. The hostages to be released would include women, children, people with severe injuries and those over age 50, according to a draft seen by The Wall Street Journal. Hamas would also hand over dead bodies.

The test will come after the first 16 days, when the parties will begin debating whether to extend the pause into a permanent halt to the fighting over the second and third stages of the deal. These stages would also include the release of all the hostages and eventually a plan to rebuild Gaza.

“The real negotiations are in Stage Two,” said Wolfsfeld, the political scientist. But, he said, “I certainly think Trump will want the cease-fire to continue. He doesn’t want an ongoing war if he can avoid it.” Previous talks have been undermined by a fundamental disagreement: Israel has wanted to get its hostages back and then continue the war, while Hamas has been loath to release captives without ending the conflict.

In the current deal, Hamas accepted verbal guarantees from the U.S., Qatar, Egypt and Turkey that Israel would continue negotiations for a permanent cease-fire after the expiration of the first phase of the deal, Arab mediators said.

According to those involved, Steve Witkoff, a real-estate mogul designated by Trump as Middle East envoy, breathed fresh life into the talks. The Biden administration worked to advance a deal with Witkoff, whom Arab mediators said made clear from the get-go that he was serious about pushing through an agreement and uninterested in endless diplomatic gestures. Witkoff met on Saturday in Israel with Netanyahu.

“It seems that Steve Witkoff, the special envoy, achieved in one meeting with Netanyahu what dozens of Biden officials could not achieve,” said Michael Oren, a former Israeli envoy to the United States.

Trump has tapped a number of longtime friends of Israel for his Middle East team. Analysts say Netanyahu will need the administration’s help as he confronts Iran, tries to cement Israel’s control over the West Bank and pursues a normalization deal with Saudi Arabia.

“As long as pressure came from the Biden administration, you could play on time. Around the corner there was a possibility of Trump,” said Abraham Diskin, an Israeli political scientist. “With Trump, you cannot do that, because you have nothing better for Israel on the horizon.” WSJ

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout