Hassan Nasrallah and other senior leaders of Hezbollah were under siege as they gathered Friday in a bunker more than 60 feet beneath the surface of a bustling working-class neighbourhood in southern Beirut.

A series of Israeli attacks killed many of the Lebanese militant group’s senior leaders, blew up its electronic devices and destroyed some of its vast arsenal of missiles. Some planned to use the meeting to express frustration that Iran was restraining them from responding more forcefully to the Israeli attacks, according to people familiar with Hezbollah’s discussions.

Around dusk, explosions shook the city above.

Israel’s air force struck the bunker with about 80 tonnes of bombs, according to several people familiar with the situation. The attack used a series of timed, chained explosions to penetrate the subterranean bunker, a senior Israeli military official said.

When it was over, a pillar of orange smoke rose above Beirut. And Hassan Nasrallah, the fierce and charismatic Islamist who had led Hezbollah for more than three decades, was dead.

His death leaves a void at the top of the world’s most heavily armed nonstate militia, which is designated as a terrorist group by the US. It was a transformative event for the Middle East. Friday’s strike capped a series of killings by Israel that wiped out nearly an entire generation of Hezbollah leaders, throwing Iran’s most valuable militia ally into disarray.

The killing showed Israel’s leaders are prepared to blow past the red lines that previously defined the country’s slow-burning conflict with Hezbollah to ensure its own security.

Israel, which has hit Lebanon with more than 2,000 airstrikes in recent days, said its military campaign is aimed at ending Hezbollah’s attacks on northern Israel that have forced tens of thousands of Israelis to evacuate from their homes. More than 700 people have been killed by the strikes in recent days, according to the Lebanese health ministry.

“What Israel is doing with this campaign against Hezbollah has opened the door to a new era in which Iran’s influence in the Middle East is going to be significantly weakened,” said Lina Khatib, director of the SOAS Middle East Institute, a think tank based in London.

Israel’s operational planning for Friday’s strike began months ago, with military officials identifying how to pierce an underground bunker in southern Beirut with a series of timed explosions, with each blast paving the way for the next one. The attack was one of the largest single airstrikes on a major city in recent history.

Israeli officials began to discuss seriously the option of killing Nasrallah in recent days, according to a person briefed on the matter. The exact timing of the strike, Israeli officials said, was opportunistic, coming after Israeli intelligence learned about the meeting hours before it occurred.

“We had real-time intelligence that Nasrallah was gathering with many senior terrorists,” said an Israeli military spokesman, Nadav Shoshani.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was in New York for the United Nations General Assembly, where he gave a defiant speech Friday to a largely empty chamber, after many delegates walked out. “We will not accept a terror army perched on our northern border able to perpetrate another October 7-style massacre,” he said.

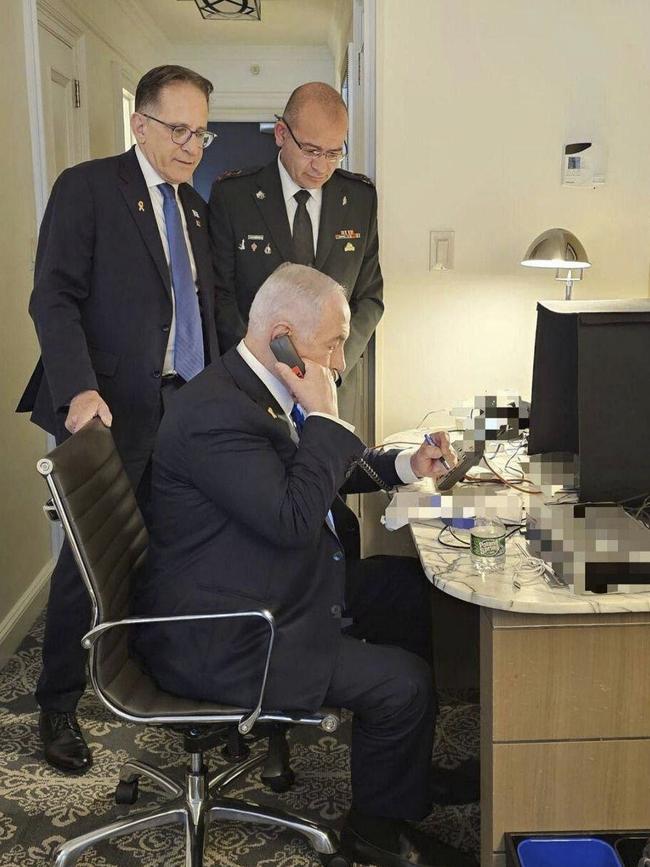

An hour after the attack, his office released a photo of him on the phone in New York, giving the green light for the strike .

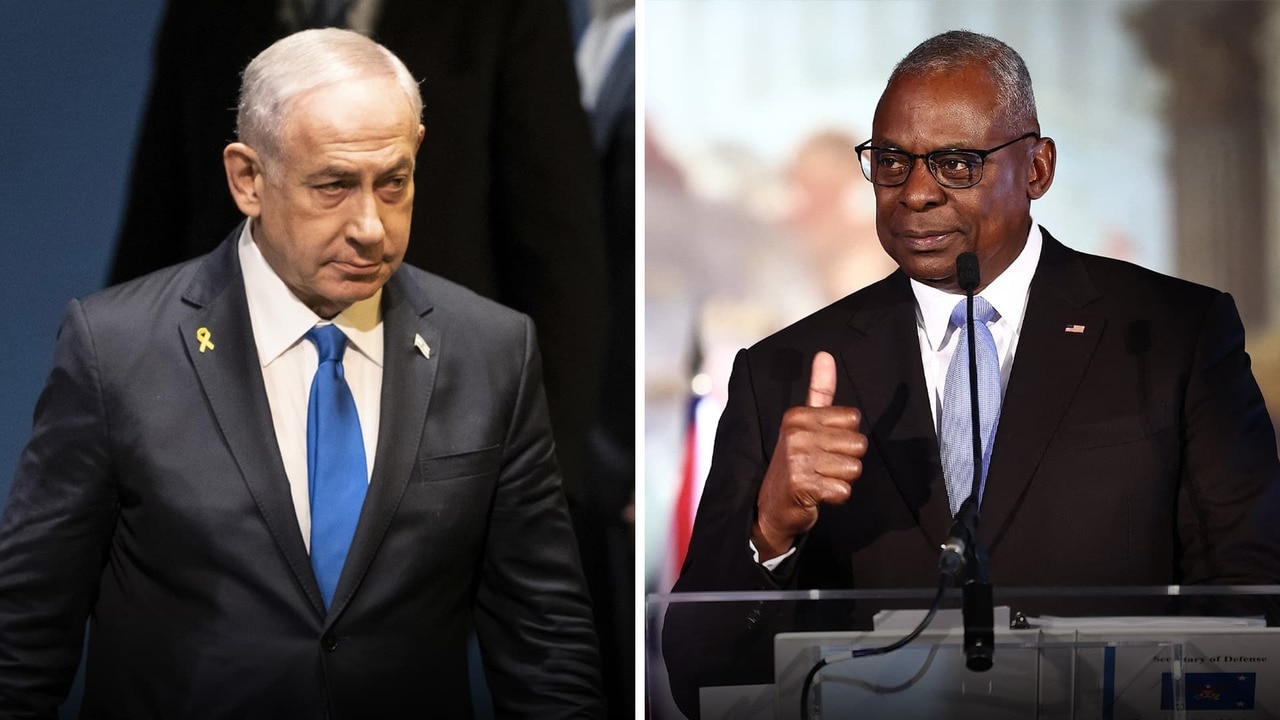

In Washington, the strike was met with frustration from top members of the Biden administration after days in which the US had tried to restart negotiations toward a ceasefire in both Gaza and Lebanon. Netanyahu had earlier in the week cast doubt on an American and French-led ceasefire initiative.

U.S. officials said they weren’t informed ahead of time about the strike, something Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin expressed concern about during a call Friday with his Israeli counterpart, Yoav Gallant, according to an official familiar with the call.

The Beirut strike replicated one key aspect of the war in Gaza: Israel’s willingness to use large bombs to achieve its military aims including the targeting of senior leaders of Hamas and Hezbollah, even in urban areas where those strikes risk killing many civilians. The Israeli military has carried out a series of such strikes in Gaza. It used eight 2,000-pound bombs to try to kill Hamas’s top military leader in July.

“What it says is that Israel is serious about stopping this persistent threat from Hezbollah, and they’re willing to accept a lot of risks of doing it,” said Joseph Votel, a retired four-star general and former commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East. “The weight of the strike was designed to ensure they had the greatest chance of being successful in killing Nasrallah.” Israel takes on a far higher risk of civilian casualties than in comparable American attacks on high-value targets, said former U.S. military officials. For example, raids that killed Osama bin Laden and the Islamic State leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, were carried out by teams of special forces on the ground paired with close air support, rather than airstrikes.

“They have a high tolerance for extreme amounts of civilian casualties, especially when it comes to high-value targets like the Hezbollah leadership or the Hamas leadership,” said Wes Bryant, a retired master sergeant and special operations joint terminal attack controller in the US Air Force.

Beirut residents have been on edge for months, watching as the violence between Hezbollah and Israel escalated. Many in Lebanon remember the devastation wrought by the last full-scale war, in 2006.

In that conflict, Israeli warplanes bombed the runways of the Beirut airport, along with residential areas in Beirut, grocery stores, gas stations and civilian infrastructure across the country. Lebanon suffered an economic crisis in the years that followed, leaving it on the brink of failed-state status, with few resources to withstand another war.

In the recent conflict, waves of Israeli airstrikes have sent thousands fleeing north and pouring into the city. Some 200,000 people have been displaced in Lebanon. The airstrike that killed Nasrallah opened yet another phase in the conflict, and spread fear and foreboding among the public.

After the strike, the Israeli military issued notices on social media warning residents of specific areas of southern Beirut to leave their buildings, using one of the hallmark tactics of the war in Gaza, where it has displaced civilians while going in to strike Hamas.

Many people said they didn’t see the warnings. They simply fled southern Beirut after Friday’s strikes out of fear following the strike on Nasrallah. Carrying backpacks and plastic bags, they spilled into central Beirut while others piled into cars and headed north.

As the sun rose, families huddled together on Martyrs’ Square, a concrete plaza in central Beirut near the Lebanese parliament and steps from the bars and nightclubs frequented by Beirut’s elite. Some sat on plastic-foam slabs while others made tents of plastic sheets to shield themselves from the sun.

“The earth shook beneath us,” said 42-year-old Fadla Qassem Sheikh, who sat with her family on the steps of the Mohammad al-Amin Mosque on the edge of the Martyrs’ Square on Saturday morning after she fled southern Beirut. “How can they drop 20 tons of bombs on women and children?” Abu Mohammed Mohsin was at his home a short distance from where the strikes occurred. “It’s not our decision whether to stay or go,” he said. If he can’t go back soon, he said he would spread a mattress on the ground and sleep in the street.

Moussa Mourad had fled his town in southern Lebanon earlier in September after he heard rumours that Israeli forces were about to hit the town, taking refuge first with a relative who lived on the road to the Beirut airport. He moved into a new apartment with his family of seven on Thursday.

A newcomer to the capital, he barely knew his way around the city. He had no idea there was a Hezbollah compound in the area, he said. On Friday evening, he had returned to his newly rented apartment to unwind with his family, after taking his son for his cancer treatment at a local hospital.

Then the bombing shook the building.

What happened next is mostly a blur. He and his family hurriedly crammed into his car and drove to Martyrs’ Square. There, they sat on the pavement gazing at passing cars until late on Friday night.

“There is an hour of my life where I can’t remember any of the details,” he said. “I just remember the sound of the ground shaking underneath us.”

– Stephen Kalin, Laurence Norman and Carrie Keller-Lynn contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout