How COVID-19 coronavirus attacks your body

Scientists have shared a basic understanding of how the coronavirus works, but there’s much to be learned.

It starts, most often, with a cough or a sneeze. Thousands of tiny, often invisible droplets of saliva or mucus disperse in the air. You walk by — within about 1.8m of the offender — and inadvertently inhale the droplets.

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 begins like most other respiratory viruses. Scientists are still studying what happens in the body when someone gets infected and how the virus in some patients progresses to the lungs, causing viral pneumonia, difficulty breathing, and even death.

The race to better understand the virus comes as global death tolls spiral, patients flood emergency rooms, and US hospitals at the centre of the growing crisis clamour for supplies. Doctors have been forced to learn much about how the virus works as they go.

But there are some things scientists know based on how other similar respiratory viruses work. That coupled with recent case reports from infected patients in China and Washington state have given scientists a basic understanding of how it works though they say there is still much to be learned.

The virus most commonly enters the nose through minuscule droplets from someone’s mucus or saliva, says Steve Lawrence, an infectious disease physician at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St Louis.

This is the primary way of spreading the virus, which is why public health experts and governments are focusing on social distancing as a prevention strategy. It can also enter through the eyes or mouth.

Once the virus’s particles enter the body, they begin to attach to a particular receptor on the surface of the body’s cells, usually starting with cells in the mucous membranes in the nose and throat. The coronavirus is distinguished by spiky proteins on its surface; these spikes latch onto cell membranes. The virus then enters the cells and disassembles so its RNA — molecules that carry instructions from DNA to the body’s cells — can start to reproduce.

“You can find very high levels of virus in the nasal passages even before people have developed cough and fevers, suggesting that it is initially an upper respiratory infection,” says Daniel Kuritzkes, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Though most people likely start with an upper respiratory infection, it’s also possible that respiratory droplets are inhaled more deeply and go directly into the lungs, says Brian Garibaldi, an associate professor of pulmonary and critical care at Johns Hopkins University. “It has a special protein that binds more tightly to cells in the lower respiratory tract,” he says.

Wherever it lands, the virus hijacks cells and starts replicating, ultimately producing millions of viral particles that flood the body.

“Like other viruses it takes over the cellular machinery of the cell and makes more copies of itself and spreads,” Dr Garibaldi says.

When your immune system recognises there’s a new virus in your body it starts using signalling molecules called cytokines to start calling in reinforcements to the site of infection. “Many of those cytokines end up causing a fever,” Dr Garibaldi says.

Once the virus has attacked enough cells in the upper respiratory system, most people will start to feel symptoms. This happens on average five days after being exposed to the virus but it can be sooner or as many as two weeks later, studies show.

These early symptoms usually include a dry cough and fever, and sometimes a sore throat, as well as aches and fatigue. Loss of taste and smell have also been reported as early signs of infection.

For the majority of people — roughly 80 per cent according to reports from China — the symptoms end there and dissipate in a few days or weeks.

But for some people, predominantly older people and those with other medical conditions, the virus keeps travelling down and invading cells in the lungs.

When the cells start moving down the respiratory system into the lungs it becomes a lower respiratory illness, which is considered more serious. That could happen two to seven days after symptoms start, Dr Kuritzkes says.

Once the virus starts infecting the cells that line the air sacs in the lungs, viral pneumonia develops, which is inflammation of the lungs. Shortness of breath is an indication that the virus is damaging the lungs.

“Those people who develop pneumonia or get seriously ill, it’s because they’ve had infection of the lung itself, not just the upper airways,” Dr Kuritzkes says.

And the lungs often face a two-way assault. There is damage from the virus but a second equally debilitating response takes place: The body’s own immune system goes into overdrive, causing more lung damage.

Some patients’ immune systems flare up, producing a lot of white blood cells that flood the infection site in the lungs, causing damage. They secrete a lot of cytokines that enhance the inflammation, Dr Kuritzkes says. “That can make it difficult for people to breathe. All this fluid that accumulates and all these extra cells that don’t belong there create a barrier for oxygen exchange,” he says.

One key feature that distinguishes COVID-19 from other viruses such as the flu is the high frequency of pneumonia, even in people with only mildly symptomatic cases, he says.

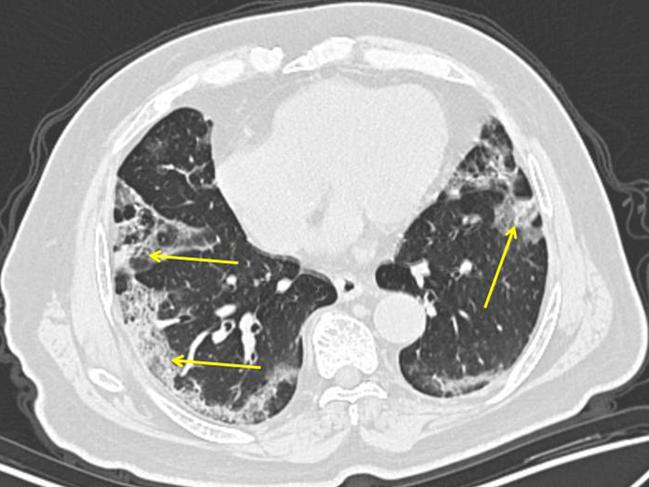

Studies of COVID-19 patients whose lungs were examined show several distinctive and unusual patterns. Adam Bernheim, a cardiothoracic radiologist at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and co-researchers studied the chest CT chest scans of 121 positive coronavirus patients from China. They published their results in the journal Radiology last month.

The researchers found a striking pattern: The pneumonia progressed along the lungs’ outer edges, as evidenced by hazy, grey circular spots.

“A normal lung is black, because it contains air,” Dr Bernheim says.

“In coronavirus with pneumonia, air is being replaced by cells, inflammation, fluid, debris and pus, so it starts to turn grey or even white.”

The spots developed in some patients within two days of symptom onset and were nearly universal in patients three days or more later. Dr Bernheim says the pattern is different from garden-variety bacterial pneumonia that the flu often leads to, which often shows one very dense white area in the lung.

When the lung becomes progressively more damaged, that triggers what is known as acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS. This typically develops seven to 14 days into the course of the illness.

The lungs become less efficient at exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide and continue to become inflamed. Patients need assistance breathing because there’s no therapy to treat ARDS.

“The ventilator is buying time for the lung to repair itself after a virus has run its course and the immune system response has calmed down, ” Dr Garibaldi says.

Matthew Arentz, a pulmonary and critical care doctor at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, published a study in JAMA earlier this month looking at the chest images of the first 21 critically ill COVID-19 patients in the U.S.

Two-thirds of the patients were from nursing facilities with an average age of 70 and most had chronic medical conditions. Eighty-four per cent required mechanical ventilation and only four people survived, says Dr. Arentz.

Chest X-rays demonstrated pneumonia in 19 of the 21 patients, all of whom developed ARDS.

Most of the patients who died were unable to maintain adequate oxygen levels due to diseased lungs. But one-third developed heart failure, which is another way some COVID-19 patients are dying.

Some doctors say that abrupt onset of heart problems seems to be another distinctive trait of COVID-19 — heart failure was reported with MERS and does occur rarely with the flu, but appears to be a striking feature in some severe cases of COVID-19, Dr Kuritzkes says.

Case reports from other countries, too, show that some COVID-19 patients experience heart failure or an abnormal heart rhythm, Dr Lawrence says.

Physicians say it’s unclear what’s causing the heart issues. It could be that people’s hearts weaken, or that the hyperactive response of the immune system stresses the heart.

Though the risk is greater for those with pre-existing heart conditions, there are also reports of patients without heart disease experiencing cardiac failure from COVID-19, Dr Garibaldi says.

“We don’t know if the virus is doing something to the heart or the heart may have been stressed by the patient’s critical illness because a lot of these patients are older and have other health problems,” Dr Arentz says.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout