Harvard has trained so many Chinese communist officials, they call it their ‘party school’

Kennedy School of Government is favoured by party cadres seeking career boosts.

U.S. schools — and one prestigious institution in particular — have long offered up-and-coming Chinese officials a place to study governance, a practice that the Trump administration could end with a new effort to keep out what it says are Chinese students with Communist Party ties.

For decades, the party has sent thousands of mid-career and senior bureaucrats to pursue executive training and postgraduate studies on U.S. campuses, with Harvard University a coveted destination described by some in China as the top “party school” outside the country.

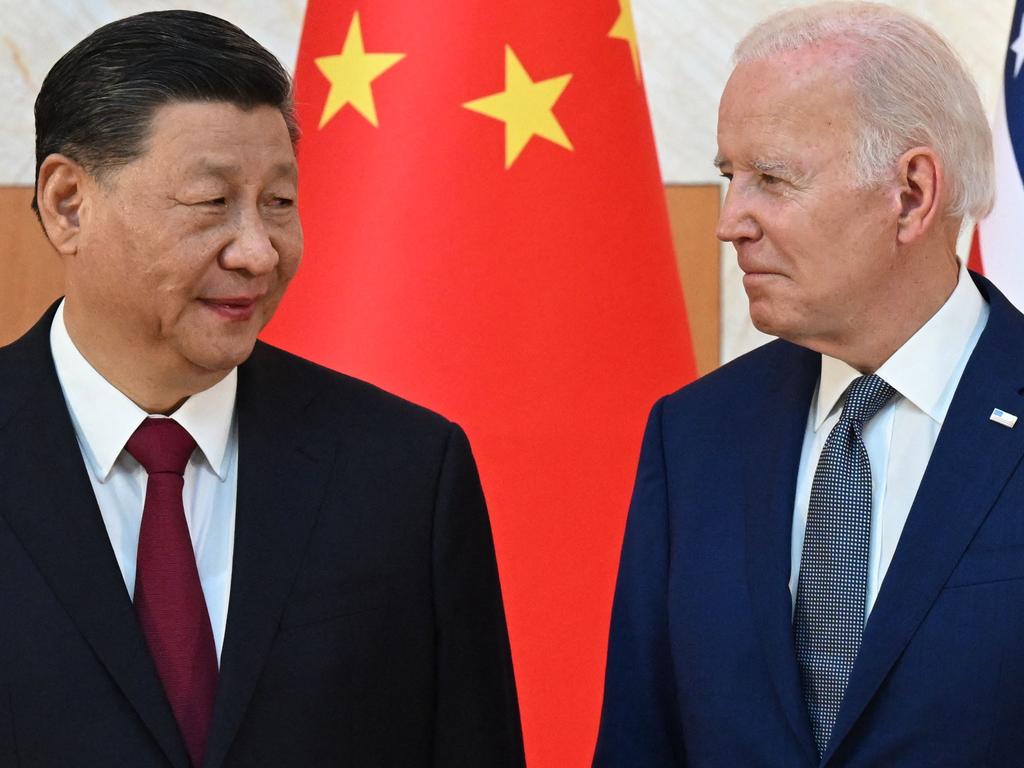

Alumni of such programs include a former vice president and Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s top negotiator in trade talks with the first Trump administration.

In an effort announced Wednesday by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, U.S. authorities will tighten criteria for visa applications from China and “aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students, including those with connections to the Chinese Communist Party or studying in critical fields.” The statement didn’t say how the Trump administration would assess Communist Party ties or what degree of connection would result in revocation of visas. In China, party membership is widely seen as helpful for career advancement — in government and the private sector — and is typically a prerequisite for officials seeking high office.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said Thursday that the U.S. move “seriously damaged the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese students.” Alleged ties with the Communist Party have emerged as a leading line of attack in President Trump’s pressure campaign against Harvard. The Trump administration said on May 22 it was revoking Harvard’s authorisation to enrol foreign students, accusing the university of working with the Communist Party, though it later gave Harvard 30 days to contest the decision. Harvard has filed a lawsuit to keep its foreign enrolments.

Harvard didn’t respond to questions for this article.

Some U.S. politicians have said that China’s Communist Party is harvesting expertise in American academia to ultimately harm U.S. interests. The Trump administration has cited these criticisms among others to back its efforts to force a major cultural shift in U.S. colleges, which many conservatives regard as bastions of liberal and left-wing ideology.

American universities have played leading roles in shaping China’s overseas training programs for mid-career officials, which Beijing started arranging at scale in the 1990s as a way to improve governance by exposing its bureaucrats to Western public-policy ideas and practices.

Other U.S. colleges that have offered executive training to Chinese officials include Syracuse, Stanford, the University of Maryland and Rutgers, according to publicity materials and other disclosures. Syracuse’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, for instance, helped set up postgraduate programs in public administration at Chinese universities in the early 2000s.

Beyond the U.S., Chinese officials have also flocked to leading universities in countries including Singapore, Japan and the U.K. Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University is among the most popular, having trained thousands of Chinese officials since the early 1990s, mostly through postgraduate programs colloquially known as the “Mayors’ Class.”

Harvard enjoys a sterling reputation among Chinese officials thanks to its record in training high-flying bureaucrats who went on to take senior government roles and, in some cases, join the party’s elite Politburo. Some observers dubbed Harvard a de facto “party school,” as the party’s own training academies for promising bureaucrats are known.

“If we were to rank the Chinese Communist Party’s ‘overseas party schools,’ the one deserving top spot has to be Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in the U.S.,” said a 2014 commentary published by Shanghai Observer, an online platform run by the city’s main party newspaper.

Li Yuanchao, a former Politburo member and China’s vice president from 2013 to 2018, attended a mid-career training program at Harvard Kennedy School in 2002. He was the party boss of the central city of Nanjing at the time, and his first class at the school focused on crisis management, he recalled in a speech when visiting Harvard in 2009.

The training proved invaluable when Li, after his return to Nanjing, had to deal with a mass poisoning in the city that killed dozens of people. “More than 200 lives were saved in time, and the suspect was captured within 36 hours. We were praised by the local people and the central government for this,” Li said in the 2009 speech. “So, when I come here again today, I want to say: ‘Thank you, Harvard!’” Liu He, a retired vice premier who was Xi’s top trade negotiator in talks with the first Trump administration, earned a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard Kennedy School in 1995. Current Politburo member and senior legislator Li Hongzhong attended a short-term program at Harvard in 1999.

While Harvard Kennedy School hosted Chinese students as early as the 1980s, Beijing started sending officials for mid-career training there in a more organised manner in the following decade, according to Chinese media reports. One program, launched in 1998, offered fellowships and executive training courses to around 20 senior officials each year.

In the early 2000s, Harvard launched another program, “China’s Leaders in Development,” through which Chinese officials would undergo a weekslong training course split between Harvard and Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University.

The program was designed to “help prepare senior local and central Chinese government officials to more effectively address the ongoing challenges of China’s national reforms,” according to Harvard.

According to newsletters published by the Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, the Harvard segment of the program has featured classes on subjects including public management, economic development and social policy, as well as visits to U.S. government organisations.

Some children of top Communist Party officials have also attended Harvard for undergraduate and postgraduate studies.

Xi’s daughter, Mingze, attended Harvard as an undergraduate in the early 2010s under an assumed name, though Harvard administrators and some faculty members were aware of her identity. She had enrolled while her father was China’s vice president and leader-in-waiting and graduated after he took power.

Other Harvard alumni with elite backgrounds include Alvin Jiang, a grandson of former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin, as well as Bo Guagua, the son of the former Politburo member Bo Xilai.

Bo Guagua attended Harvard Kennedy School from 2010 to 2012 and earned a master’s degree in public policy. His father was purged in 2012 and was sentenced to life imprisonment the following year on charges of bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power.

Harvard’s China connections have also helped some of its top scholars gain access in Beijing. Graham Allison, a former dean of Harvard Kennedy School, has been granted meetings with Xi and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi over the past year, during which the professor spoke about his views on U.S.-China relations.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout