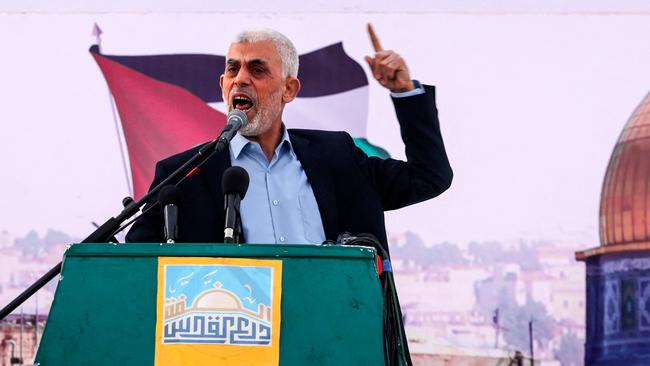

Hamas’s Gaza chief, once a high-profile prisoner in Israel, is now a ‘dead man walking’

Israeli officials blame Yahya Sinwar for the October 7 terror attacks and is hunting him down, most likely to the labyrinth of tunnels used by Hamas militants in Gaza.

During two decades in Israeli prison, Yahya Sinwar learned Hebrew fluently and devoured local newspapers and television. Now, the most senior Hamas leader in Gaza is using that knowledge to fight a war against Israel.

Israel has accused Sinwar, alongside the commander of Hamas’s military wing, Mohammed Deif, of co-ordinating the brutal Oct. 7 attacks that killed 1400 Israelis, including 1000 civilians. Hamas has taken about 200 people to Gaza as hostages.

The Israeli military says it is hunting him down as it targets senior Hamas officials in the Palestinian enclave. Israeli officials believe he is likely hiding in the labyrinth of tunnels used by Hamas militants in Gaza. Last weekend, Israeli military spokesman Lt. Col. Richard Hecht called Sinwar a “dead man walking.”

“I do believe that Deif committed the plan but the real mind, the brain of this attack was mainly Yahya Sinwar,” said Michael Milshtein, a former intelligence officer for Palestinian affairs in the Israeli army. “He really understands how the Israelis will behave, and how they think, and how they will respond.”

As Hamas leader in Gaza, Sinwar is part of a complex and secretive Hamas leadership structure that includes its military wing and a political arm. In all, there are roughly 15 people at any one time in the senior political leadership, which determines the direction of Hamas via consensus, according to the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank.

“I think the tragic events over the last week and Hamas’s brutal use of violence … reflects the dominance of the military movement over Hamas in a way that we haven’t seen before,” said Hugh Lovatt, a fellow at the ECFR.

Ismail Haniyeh, who led the group successfully in elections in 2006 for a legislature that later fell apart, heads Hamas’s council of leaders from Doha and helps manage its relationship with gas-rich Gulf benefactor Qatar.

Another official, Saleh al-Arouri, is the deputy political chief based in Beirut, where he helps oversee Hamas’s relationship with Hezbollah and Iran as well as the group’s operations in the West Bank.

For a time, Western officials considered whether the group was possibly moderating its position on Israel. In 2017, Hamas updated its charter of principles to indicate that it would be willing to recognize the establishment of a Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank -- territories Israel captured in 1967 -- rather than the entirety of historic Palestine. Some viewed the move as effective recognition of Israel. Hamas’s original 1988 charter vowed to destroy Israel.

But after the revised charter did little to alter the international community’s hostile view of Hamas -- the U.S. has designated the organisation a terror group -- Sinwar was elected leader in Gaza in 2017. He succeeded Haniyeh, who took over as head of the overall leadership in Doha from Khaled Meshaal, considered a moderate by international observers.

It was a sign of the more militant turn Hamas was taking. Israeli security officials consider Sinwar one of the more hawkish members of Hamas and a bridge between the political leadership and the militant wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, led by Deif.

Deif hasn’t been seen in public for years but issued a statement as the Oct. 7 attacks unfolded, saying his army had launched an operation in response to Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands. Sinwar, who has a greying beard and is often pictured scowling, has been silent since the attacks.

Spokespeople for Hamas didn’t respond to requests for comment. Akram Attallah, a Palestinian journalist from Gaza who has met Sinwar several times, said the attack on Israel suggests the group is using more violent methods to build possible leverage for any future negotiations.

Born in the early 1960s in a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, Sinwar became a student activist and was close to Hamas’s founder, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, a half-blind cleric who was assassinated by Israel in 2004, according to Israeli officials.

When Hamas shifted from being an Islamist movement to an armed group during the Palestinian uprising in the late 1980s, known as the first intifada, Sinwar helped form the forerunner to its military wing, according to Israeli officials. He also established an internal security unit that hunted informants, according to Hamas officials.

In 1988, he was arrested and later convicted of killing Israeli soldiers and given four life sentences.

In prison, Sinwar became one of the most senior incarcerated Hamas officials. He also spent hours talking to Israelis, learning the culture, and “was addicted to Israeli channels,” said a former senior Israeli prison-service official. Many Hamas members have spent time in Israeli jails, so prisoners have long been an influential part of the group’s leadership.

At some point during Sinwar’s incarceration, Israeli doctors saved the Palestinian’s life when he developed a brain illness and was operated on in an Israeli hospital, according to the former prison official and former military officials.

When Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier, was kidnapped by Hamas in 2006, Sinwar was considered in negotiations between Israel and Hamas that later led to the release of 1,027 Palestinian prisoners in return for the one Israeli.

According to Gershon Baskin, who worked at the time as an interlocutor between the Israeli intelligence service and Hamas, Sinwar only just made the cut to get out as Israelis had reservations about releasing him. “He was the most senior figure in the prisons who was released,” he said.

After release, Sinwar rose quickly through Hamas ranks.

Hamas members chose Sinwar to lead in Gaza in 2017. Other Hamas leaders assured members that his election as Gaza chief would not drag the group into new rounds of internal and external violence, according to Hamas officials who spoke with The Wall Street Journal.

He developed a reputation as both a hard-liner and a pragmatist, deploying a dual strategy of engaging with Israel, while also turning to violence at times to achieve political leverage. His children, born after he left prison, often attended high-level meetings with him. He told one Hamas official that he spent two decades waiting to have children while in prison, so didn’t want to waste time.

Sinwar also pursued failed talks with the Fatah, which dominates the Palestinian Authority, the group that governs the West Bank, about reconciling with the rival Palestinian faction.

In a rare 2018 interview published in Israeli media, Sinwar told an Italian journalist that war wasn’t in Hamas’s or Israel’s interests. “For sure, it’s not in ours: Who would like to face a nuclear power with slingshots?” Egyptian officials who dealt with Sinwar said he led a campaign to improve the group’s relationship with Egypt, which had soured after a 2013 coup removed from power in Cairo the Muslim Brotherhood, of which Hamas is an offshoot.

President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi then closed off access to the Gaza Strip from Sinai. “He is a real statesman, yet a crude fighter,” an Egyptian official said of Sinwar.

In 2021, Sinwar showed his harder side when Hamas launched rockets at Israeli cities in response to tensions between Palestinians and Jews in Jerusalem, sparking an 11-day conflict.

A Hamas official said Sinwar doesn’t just see himself as a leader inside Hamas, but as someone with a mission to protect Jerusalem and the Al Aqsa mosque there, one of Islam’s holiest shrines.

Like now, Israel said it was seeking to kill Sinwar in 2021 too. After a cease-fire at the time, the Hamas leader walked openly around Gaza in what many Palestinians perceived as a taunt to Israel. Later, at a rally, he was photographed holding the child of a dead Hamas member and an AK-47 rifle.

According to Hamas officials, Sinwar often advocated for a wider battle with Israel where Hamas could dictate new rules of engagement. In a speech in April, he said what he called the Axis of Al Quds -- Hezbollah, Iran and Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank -- was ready for a fight with Israel.

“We will do our job of defending our Jerusalem, our Aqsa, our West Bank, our people and our women,” he said.

— Abu Bakr Bashir contributed to this article

The Wall Street Journl