Geena Davis wants to alter the way we see women on screen

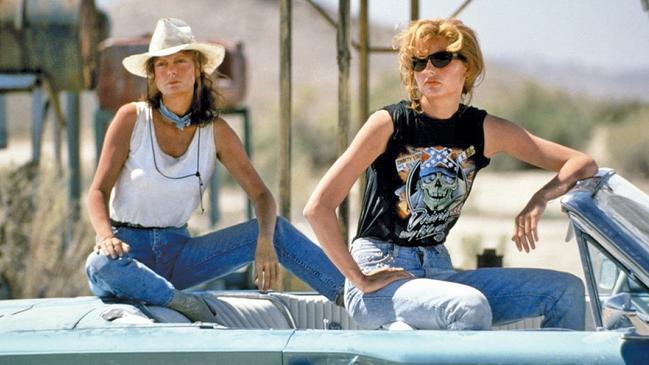

After starring in blockbusters like Thelma & Louise, the actress is challenging Hollywood to make more ‘insanely successful’ movies with female leads.

When Thelma & Louise became a box-office hit in 1991, critics said it “was going to change everything”, Geena Davis says. It seemed thrillingly clear the feminist road flick starring Davis and Susan Sarandon would spur Hollywood to make more pictures with and for women. A year later, when Davis starred in the enormously popular A League of Their Own, about an all-female professional baseball team, pundits similarly predicted a glut of new sports movies starring women.

“I was like, ‘Hot dog! I’ve been in two movies that changed everything!’,” Davis, 65, says over video from her home in Los Angeles. Yet as she writes in her new memoir, Dying of Politeness, published this week: “Nothing changed.”

“Every four to five years another movie would come out starring women that was successful, and again people would say, ‘This changes everything!’,” Davis says, offering The First Wives Club (1996) and The Hunger Games (2012) as examples.

“But then Hollywood would return to the idea that men won’t watch women but women will watch anything. It was so frustrating.”

In 2004, she was so troubled by the paucity of female roles, particularly for women over 40, that she founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, a data-based research organisation that works closely with the industry to make films and shows more diverse. After years of pushing studios and networks to see how female characters were often hypersexualised, underemployed and outnumbered, Davis says family shows and films now have an equal number of male and female leads. “The data really was the magic key,” she says. Her work with the organisation earned her a special Academy Award in 2019 and an Emmy this year.

Given her roles on screen and behind the scenes, Davis seems like someone who has little trouble leaning in. In her memoir, however, she makes it plain that her “journey to badassery” was in fact long, winding and riddled with insecurities.

As a gawky, “cripplingly polite” teen from Wareham, Massachusetts, just north of Martha’s Vineyard, Davis says she felt so self-conscious about her 2m frame that she tried to shrink her personality to take up less space.

When she wasn’t muffling herself, others did it for her. “It seemed like there was always somebody to say, ‘Oh, don’t do that, don’t laugh like that, don’t wear that’,” she says. She now speculates that becoming an actor offered a kind of escape: “I could be somebody different and not be judged for who I was as myself.”

Despite her self-doubts, it never occurred to Davis that she might not make it as an actor. On her first day in Boston University’s acting program, she recalls a professor who warned that probably only 1 per cent of the gathered students would earn a living as performers. “I was floored,” Davis writes. “I quietly looked around the room at my new classmates and thought, ‘Oh, these poor kids!’.”

Having strategically dropped her “thick Cape Cod accent” in college, Davis arrived in Manhattan in 1978 with plans to break into films by becoming a model first. “It was really crazy thinking, but it actually worked,” she says. Thanks to a strong audition and some “airbrushed, perfectly lit” photos of her in a Victoria’s Secret catalogue, she got to play a soap-opera actor who spends a lot of time in her underwear opposite Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie (1982).

“To have that be my first experience was just incredible,” Davis says. Acting liberated her from her self-consciousness, and she says Hoffman offered all sorts of advice for the “career he seemed sure I would have”.

Among other things, he told her how to gently rebuff sexual advances from fellow actors: “Oh, I would love to … but I don’t want to ruin the sexual tension between us.” She writes that she promptly used the script on Jack Nicholson, who replied: “Aw, man, who told you to say that?”

In Hollywood, Davis often heard she wasn’t “conventionally pretty enough” to play the usual female roles, which suited her fine. “I didn’t want to just be the girlfriend of the guy who has adventures. I wanted to be doing interesting stuff, too,” she says. She carved out a niche playing it straight in some weird films, such as The Fly (1986) and Beetlejuice (1988), and playing it weird in more conventional ones, such as The Accidental Tourist (1988), for which she won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress.

Davis sensed early on that she wasn’t supposed to complain about sexual harassment. “The feeling was that no one would hire you again, so we kept everything a secret,” she says. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, she decided to be more open about how experiences on certain film sets left her feeling vulnerable and ashamed.

“I didn’t know how to avoid being treated that way,” she writes. “I shut up and played along.” She said it wasn’t until she worked with Sarandon on Thelma & Louise that she learned it was possible to be both nice and assertive: “It was such an education to watch a woman say exactly what she thinks or wants.”

After the rush of films through much of the 1980s and 1990s, Davis was surprised when the offers slowed to a trickle the moment she hit 40. “It was devastating,” she writes. “I wanted to do more of the job I lived for, not less.” She threw herself into archery, almost qualifying for the 2000 Olympics, and into parenting her three children with her now ex-partner, Reza Jarrahy, a paediatric plastic surgeon.

It was while she was watching a kids’ TV show with her daughter 20 years ago that Davis found herself wondering: Where are the girls? When Davis’s institute first studied movies and TV in 2008, the data showed male-speaking characters outnumbered female ones three to one. In her book, Davis quotes an email from Dan Scanlon, a Pixar animator, saying these statistics helped convince him of the need to make films more inclusive. According to Institute figures, Pixar’s Monsters University (2013), which Scanlon directed, had a 350 per cent increase in female characters from the original Monsters Inc (2001).

“When you break it down, female lead characters speak and are on screen around a third of the time of a male lead, but things are still profoundly different from where we started,” Davis says. “It’s finally starting to sink in that films about women can be insanely successful.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout