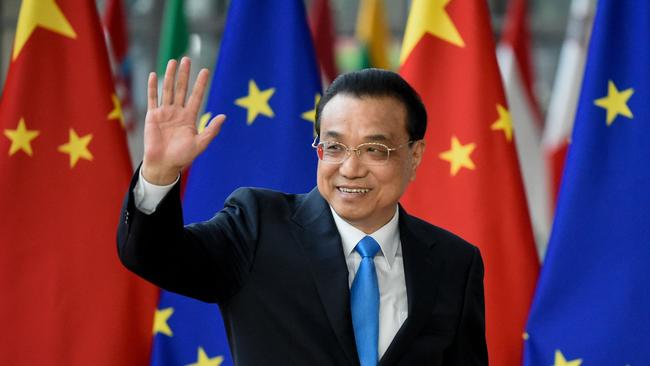

Li Keqiang, Chinese ex-premier who helped shape economic policy, dies at 68

Li Keqiang, China’s No. 2 official until his retirement last year, suffered heart failure.

Former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang died Friday after suffering heart failure, state media said. He was 68.

Li, who served a decade as premier until March, was in Shanghai when he experienced a sudden heart attack on Thursday, the official Xinhua News Agency said in a brief report.

The former premier died shortly after midnight after “all-out efforts to rescue him failed,” said Xinhua, which didn’t provide further details.

Li was the Communist Party’s No. 2 official from 2012 to 2022. He stepped down from his positions in the party leadership at a twice-a-decade party congress in last October, when Chinese leader Xi Jinping secured his third term as the party’s general secretary.

Li was being tipped as China’s possible next leader in March 2007 when he visited the Beijing residence of then-US Ambassador Clark T. Randt, Jr.

Over dinner, the rising Communist Party official made a frank declaration: China’s official economic statistics are “man-made,” and therefore unreliable, according to a leaked diplomatic cable.

Li never reached the pinnacle of party rule in China, but he got close, and his assessment of official economic data fundamentally altered how economists measured the country’s development.

As premier under Xi, the enigmatic party man with a friendly face fell in line behind the leader and remained there for a decade before retiring in 2023. Li’s reasoned policymaking softened the sharp edges of Xi’s politicised rule – but ultimately had limited impact.

He was born on July 1, 1955, to a county level Communist Party official in one of China’s traditionally poorest provinces, Anhui. In his late teens, Li was dispatched to an agricultural commune as a “sent-down youth,” a deprivation of Maoist rule where young people were told to learn from peasants, according to a biography produced by Brookings Institution.

Li later joined the party, and jumped into a post-Cultural Revolution wave of entrants to college. With degrees in law and economics, Li earned an intellectual image that set him apart from the engineers China usually produced.

As a PhD student in economics at Peking University, Li studied under Li Yining, a well-known economist whose theories were instrumental in steering state-owned enterprises toward profitmaking, according to the Brookings biography.

After school, Li climbed the party ladder quickly and before he was 50 had run two provinces.

Li’s reputation took a hit in the early 2000s when he appeared to play down and mismanage a Chinese AIDS health crisis while in charge of Henan province. Tens of thousands were infected when they sold their blood plasma because local authorities never screened for AIDS. By failing to blow the whistle on the subsequent cover-up Li and other politicians likely worsened the epidemic, according to human rights and civil society groups at the time.

To offset the narrative of a tainted political rising star, government-controlled media later lauded Li as a combatant against AIDS and a champion of its victims. A prominent Chinese AIDS activist, speaking to the Associated Press, graded Li differently: “He’s probably not a bad guy, but he’s not shown himself to be very capable of managing crises in a strong and responsible way.” Li was hoisted toward the apex of power by the political faction led by Hu Jintao, who helmed the Communist Party in the first decade of the 2000s. By 2007, Li had a seat on the party’s board of directors, the Politburo Standing Committee, and was positioned to potentially succeed Hu.

But in its then-once-a-decade leadership reshuffle in 2012, the party instead gave Xi the top job and installed Li as premier.

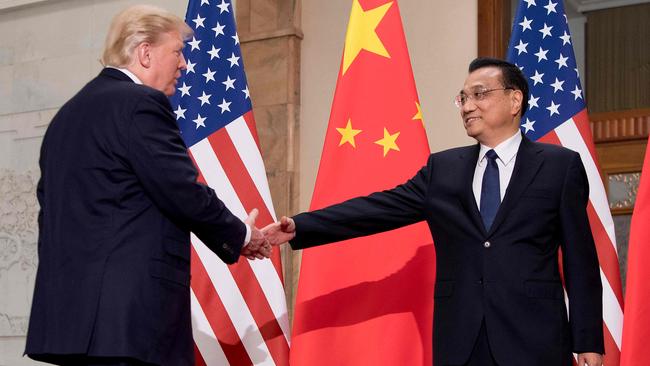

As with the US vice presidency, the importance of the Chinese premiership hinges on the top leader. Like Mao Zedong’s premier, Zhou Enlai, Li had the superior education, and apparent competence in domestic and international affairs, including English skills, but served a domineering autocrat.

Soon Mr Xi was establishing himself as China’s most consequential leader since Mao. He consolidated power by taking personal charge of portfolios like the economy that were traditionally handled by the premier, marginalising Mr. Li and sparking questions of what could have been.

Sometimes when Mr Li failed to parrot political slogans being promoted by Mr Xi, or seemed to contradict him in speeches, speculation arose of tension between the two. Since Mr Li never revealed his true thoughts about Mr Xi publicly, they remained a mystery.

Subordinated, Mr Li made technocratic contributions.

He pledged to “tackle pointless formalities, bureaucratism” – red tape – and got credit for slashing the time it took to register a business in China to under 10 days by the time he left office, from close to 35 when he started, according to World Bank numbers. Yet, Mr Xi’s anti-entrepreneur policies undermined the achievement.

One area where Mr Li made a lasting impact: his scepticism about Chinese statistics, which echoed through global markets when it came to light in 2010 courtesy of Julian Assange’s WikiLeaks. According to the U.S. ambassador’s leaked cable, Mr Li said he tracked Chinese electricity consumption, railway cargo volumes and loan dispersals since the official gross domestic product “figures are ‘man-made’ and therefore unreliable.” It was cold water from a senior official on ever-sizzling GDP numbers, at the time one of China’s proudest achievements. Soon a cottage industry of alternative ways to gauge Chinese economic activity appeared, and in honour of Mr Li those unofficial measures were collectively dubbed “Likonomics.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout