Evan Gershkovich and my time in a Moscow prison

Like Evan Gershkovich, I was a reporter in 1986 when the KGB swooped during a catch-up with a ‘friend’ and accused me of spying.

I was Moscow bureau chief for U.S. News & World Report, on Aug. 30, 1986, when the KGB arrested me and falsely accused me of being a spy. I know what Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and his family are going through.

I had only days left on my five-year tour. I met a friend, or so I thought, to say farewell in a park near my apartment. We exchanged parting gifts. A white van I had noticed earlier pulled up beside me. The door slid open abruptly and half a dozen men emerged. A heavy-set man threw me forward, pulled my hands behind my back and snapped handcuffs on my wrists.

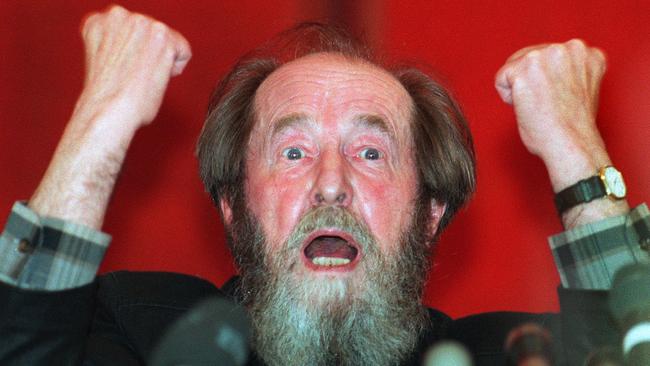

Evan Gershkovich was arrested in Yekaterinburg, Siberia, where he had been reporting on average Russians’ sentiments about the war in Ukraine. He was accused of espionage and remanded to Lefortovo prison in Moscow. I, too, was taken to Lefortovo, which has been used to house prisoners when Moscow wanted to make an example of them — including prominent dissidents Natan Sharansky and Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

I was lined up and photographed outside the prison holding the plastic bag containing the gift my so-called friend had given me. Then I was ushered into a chamber where I was confronted by a KGB interrogator as well as a translator who spoke poor English. Since I speak Russian fluently, I declined the translator.

The temptation is to communicate truthfully, quickly and in a way that explains your actions. In retrospect, that was a tactical mistake. Had I refused to speak Russian, I could have slowed and perhaps thwarted the interrogator’s investigation.

I had two tours reporting in Russia separated by 20 years. I worked for United Press International in the 1960s and for U.S. News in the ’80s. It was difficult to talk to average Russians in the 1960s, because they had been trained to not speak to foreigners. During my second tour people were more relaxed, and reporters were able to communicate more broadly and easily.

But reporters working in Russia were and still are accredited by the Foreign Ministry. You were given a press card covered in blue leather, which you had to show when asked. In Russia, you are frequently asked to produce your documents.

The moment a correspondent arrived in Russia, the KGB opened a file and would keep tabs on you at all times. That was true in the ’60s and 20 years later, and I assume the practice continues today. They gather information about where you went, who you saw, if you were gay or any other detail that might be used against you if they needed it.

We used to joke that in Russia, burping was enough to get you arrested. There were “closed” zones where you couldn’t travel. Your apartment was bugged. We held sensitive conversations outside even when the temperature was below zero.

As the American son of Soviet-born Jewish émigrés, Mr. Gershkovich has family links to Russia. I am the American grandson of a Russian general who fled after the Russian Revolution. A reporter who can speak Russian can investigate in ways that correspondents can’t if they work through a translator — who typically reports back to the authorities. Arresting a journalist who speaks Russian and has family ties to the country is designed to send an intimidating signal to others.

“Stay away from Russia,” my father warned me. “The Bolsheviks don’t give a damn about your American passport. If you go to Moscow, you’ll get arrested and end up in the salt mines.”

But the country always drew me back — its people, its culture, its role on the geopolitical stage.

My case was resolved after intense negotiations between Secretary of State George Shultz and Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze. I was released after a month along with two human-rights dissidents. We were exchanged for a physicist from the Soviet United Nations mission who had been caught red-handed in the New York subway receiving classified U.S. information. Years later, at a public talk at Harvard, I had the chance to ask Mikhail Gorbachev, the Communist Party general secretary at the time of my captivity, about my case. He essentially admitted that this was just the way the two countries operated during the Cold War.

The rules of engagement between Russia and the U.S. have shifted dramatically since the Cold War and against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Washington and its allies have imposed a broad set of sanctions in response.

The International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin for human-rights abuses including the targeting of civilians. It remains to be seen how the Gershkovich case will be resolved.

Reporting in Russia has always been risky. The authorities there have never been comfortable with the open flow of information, and they have recently imposed new restrictions on public protests. Several Western news organisations pulled their correspondents to protest recently passed laws that essentially ban independent reporting about the Ukraine invasion. Much of Russia’s independent media have been forced to shut down or to persevere outside the country.

We need to protect and honour the bravery of foreign correspondents, photographers and stringers all over the world, reporting in difficult and dangerous circumstances. And to my fellow Russian correspondent Evan Gershkovich: Courage.

Mr. Daniloff was Moscow bureau chief for U.S. News & World Report, 1981-86. He is author of “Two Lives: One Russia” and “Of Spies and Spokesmen: My Life as a Cold War Correspondent.”

The Wall Street Journal