Europe’s economy declines at record pace

The public health crisis sparked by the new coronavirus ricocheted through Europe’s economy in the first quarter.

The public health crisis sparked by the new coronavirus ricocheted through Europe’s economy in the first quarter, causing a record decline that was more severe even than in the US, an ominous sign for the global economy.

The eurozone’s gross domestic product fell 3.8 per cent versus the final three months of 2019, according to data released on Thursday, as measures imposed to limit the pandemic’s spread stalled everything from schools to factories to churches.

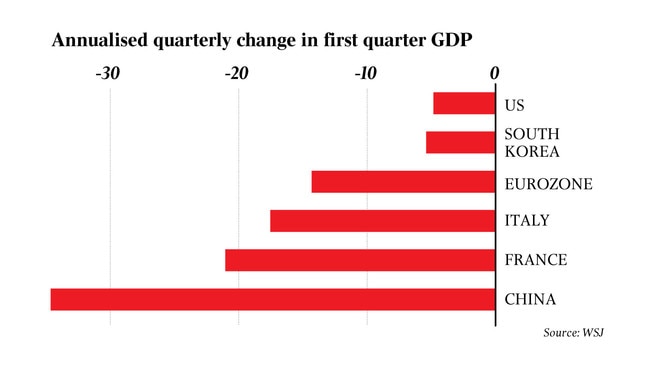

The economy shrank by 14.4 per cent on the year, far exceeding the 4.8 per cent contraction in the US over the same period. That largely reflects Europe’s earlier and broader lockdown.

“The euro area is facing an economic contraction of a magnitude and speed that are unprecedented in peacetime,” European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde said. “Measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus have largely halted economic activity.”

The data, along with other fresh numbers from around the world, reflect the depth of pain the world economy is likely to experience for months to come. They underscore the tough decisions facing Western policymakers, many now trying to reopen their economies while protecting people against new surges in infections.

The data also expose divergences in the economic dislocations both within the eurozone and among major global economies, portending political friction even after the pandemic ends. Northern European countries, for instance, shrank far less than their Mediterranean counterparts.

The severity of the contraction in the eurozone — the 19 countries that use the euro as their currency — suggest more economic pain for the US. The US had a surge in infections and lockdowns weeks later than did European countries such as Italy and Spain.

Indeed, economists expect to see an even sharper fall in the eurozone during the second quarter. With restrictions in some countries only starting to ease, a larger chunk of second-quarter output will be lost than in the first quarter. Ms Lagarde said the three-month drop through June could be almost four times as large.

On Thursday, the European Central Bank signalled its willingness to expand its efforts to buffer the impact of the economic crisis, including a €750bn ($1.25 trillion) program to buy the bonds of governments that are themselves spending huge sums to support their economies.

France was among the hardest hit by a nationwide lockdown announced on March 17. The 21 per cent annualised economic contraction recorded in the first quarter was the largest since records began in 1949, exceeding the decline in 1968, when the economy was slammed by factory strikes and student protests.

Some rebound in activity in the eurozone is expected in the second half of the year, but economists no longer expect the lost output to be quickly recovered. ECB economists expect the economy to shrink by between 5 and 12 per cent this year, Ms Lagarde said.

One unknown is how rapidly consumers will return to normal patterns of behaviour after the restrictions have been lifted.

“Fear of renewed outbreaks could make households more cautious,” said Olivier Vigna, an economist at HSBC.

In recent days, European governments have laid out plans to unlock their economies without triggering new infections. They plan a gradual lifting of lockdown measures in May, a reopening that will stretch well into the northern summer and is carefully calibrated to prevent new outbreaks. Authorities have warned they will impose new restrictions if infections surge.

Next week, Spain will allow small shops to open, and Italy will permit manufacturing and construction to resume. However, Italy and France continue to ban non-essential travel between regions, while Italian schools will return only in September, and public masses remain banned in the country for the moment.

The eurozone’s northern members appear to have suffered more modest declines than their southern counterparts. Austria reported an annualised decline of 9.6 per cent, while Italy’s GDP fell by 17.6 per cent and Spain’s by 19.2 per cent.

That widening divide poses a challenge to the long-term viability of the euro, since it feeds political tensions over how and whether to share the burden of the coronavirus pandemic.

In Italy, corporate revenues will fall 20 per cent this year, according to consulting firm Cerved Group, with some sectors, such as tourism, expecting a 75 per cent decline. The failure of companies to service their debts could push non-performing loans at banks to €189bn from €73bn, Cerved estimated.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout