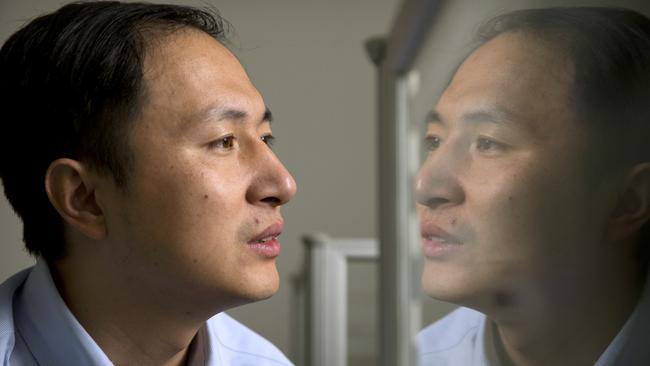

Dr He Jiankui created first gene-edited babies, then disappeared

Dr He Jiankui broke all the rules to create the world’s first gene-edited babies.

Two sisters entered the world prematurely one October night last year by emergency caesarean section. Staff at the Chinese hospital swaddled them in white, laying them in incubators.

The twins had a secret almost no one at the hospital knew. One man who did know was there, waiting — a US-educated researcher, Dr He Jiankui, who had flown into town to see them.

The twins were his creations, the world’s first known gene-edited human babies.

He had worked toward this for two years, altering their genes as embryos to try making them resistant to their father’s HIV infection. Dr He (pronounced “huh”) gave them pseudonyms, Lulu and Nana.

“I’m 70 per cent happy and 30 per cent uncertainty,” he said in an English voice message to a colleague that night.

His unease proved prescient. When the news broke, peers in China and abroad condemned him for manipulating life’s building blocks using a relatively untested gene-editing tool.

Gene-editing trials involving terminally-ill adult humans are ongoing. But tinkering with embryos is more controversial because changes in them will pass to future generations, meaning a tiny blip could have far-reaching consequences.

At a November 28 Hong Kong summit of leading geneticists, participants bombarded Dr He with questions about his methods and ethics.

Experiment “illegal”

A day later, Chinese officials declared his experiment illegal. Authorities in January detained him after an initial probe alleged he forged an approval document and acted in “pursuit of personal fame.” He hasn’t been publicly heard from since November.

Attempts to reach Dr He, who appears to remain in custody, weren’t successful.

His wife declined to comment through a person close to him. It isn’t clear if Dr He has legal representation.

Dr. He, now 35, left behind the mystery of what motivated him to defy his field’s widely held ethical principles, how he carried out his trial in stealth, why nobody stopped him — and why he was so stunned by the backlash.

A picture of just how far the scientist went to fulfil his dream emerges from a Wall Street Journal examination of his notes, emails, voice memos, clinical-trial documents and from interviews with people who knew him, some of whom were familiar with his trial, and the birth of the babies.

His drive and interests were hardly secret: A small group of highly regarded Western peers watched from the sidelines, offering advice and urging caution.

Dr He held the scientist’s ambition to make history, people who know him said. He also wanted to address what he saw as an injustice in China against families with HIV-positive parents, who are barred from fertility treatments.

Secret implantation

The scientist, who hadn’t run a human trial before, didn’t tell the doctor who implanted the twins’ mother that their genes were edited, and he kept the nature of his experiment secret from the hospital where it took place, said people familiar with the details of the trial. He faked the father’s blood test to avoid detection of his HIV, according to these people. He succumbed to the hopes of his patients, against his own medical judgment, and impregnated women eager to conceive.

A deeply patriotic man, Dr He had expected plaudits from Beijing for helping in its goal of making China a force in genetic science, people who know him said.

“He always spoke in a way as though he wanted to do good for the sake of his nation,” said Stanford University physician and neurobiologist William Hurlbut, who knows Dr He but says the researcher didn’t tell him of implanting edited genes.

“What’s so ironic is that he will be punished badly.” Dr He ignored Western scientists’ warnings that implanting edited embryos risked flouting his field’s ethical norms. None appear to have gone beyond giving warnings.

Rice University biochemical and genetic-engineering professor Michael Deem appears in a video of a meeting with parents who volunteered for the trial, in videos the Journal viewed. Dr Deem, the Chinese scientist’s former doctoral adviser at Rice, was listed as a co-author of a research paper on the twins’ birth.

A lawyer for Dr Deem said his client commented on Dr He’s research but didn’t conduct it and that Dr Deem had asked that his name be retracted from the paper.

Rice is investigating Dr Deem’s role and declined to comment.

Stanford, where Dr He also studied, said it concluded its professors weren’t involved in his research.

“Everybody who knew anything should quit pointing fingers and come forward and say what are we going to do now — why we felt there was good and bad in this and how no one seemed to know how to proceed,” said Dr Hurlbut, who said he began suspecting the Chinese researcher was planning such an experiment as their conversations deepened over many months.

Authorities have kept the location of Dr He’s experiment secret. China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and a local agency investigating Dr He didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Gene ethics

It is illegal to implant a genetically-modified human embryo in much of the Western world. The US forbids the Food and Drug Administration, whose sign-off is needed for such an experiment, from considering it.

China doesn’t have a law, but a 2003 guideline says “genetic manipulation of human gametes, zygotes and embryos for reproductive purposes is prohibited,” without outlining penalties.

A new gene-editing tool named Crispr-Cas9, which holds the promise of new disease treatments, has made ethics questions more urgent. The tool acts like molecular scissors that can target specific genes, cutting and splicing them to prevent or cure diseases.

One broadly held view is that it is too early to use Crispr on the human “germ line” — genes of sperm, eggs and embryos — because changes will pass on for generations and present the spectre of unintended consequences to the human race.

Lab research has shown Crispr-Cas9 can edit genes other than the ones intentioned. This means it could disrupt other genes, impairing functions or predisposing people to infections.

The latest international guideline came in a 2017 report from the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, and stood at odds with existing legislation in the West.

It didn’t call for a ban on implanting edited embryos, saying it should be done “only for compelling medical reasons in the absence of reasonable alternatives, and with maximum transparency and strict oversight.”

Some scientists objected to Dr He’s trial saying HIV protection wasn’t an unmet need — a fertility treatment can wash the virus off sperm to reduce transmission risk.

Dr He held that it was an unmet need among China’s HIV-positive parents who, banned from fertility clinics, didn’t have that option.

He also held that gene editing could make offspring resistant for life to HIV, not just a parent’s infection.

“You could see that people in the West were totally outraged because you never need that here,” said Stanford biophysicist Stephen Quake, in whose lab Dr He once worked.

“But I can see why there may be a different view in China of what he did and a justification for it.”

The son of rice farmers, Dr He graduated with a physics undergraduate degree in China and a Ph.D. from Rice, then switched to biology.

He forged ties with Dr Deem, a physicist who moved into biochemical engineering, and they published papers together. In 2010, he took a postdoctoral position in Dr Quake’s Stanford lab.

He returned to China as a biology professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology.

In 2012, he founded a gene-sequencing company, Direct Genomics, enlisting to its advisory board influential scientists including University of Massachusetts molecular biologist Craig Mello, a 2006 Nobel laureate.

“I want to create the first gene-edited humans”

Dr He turned his attention to Crispr-Cas9, invented in 2012. In 2015, a group of Chinese researchers provoked a firestorm after using it to edit “non-viable” human embryos that can’t result in pregnancies.

American scientists called it irresponsible to use the still-unproven tool on human embryos.

But it was a heady time for scientists in China, with President Xi Jinping urging them to “innovate, innovate, innovate!” and the Communist Party laying out goals to be a technological world player.

Dr He began using Crispr in 2016 to edit the genes of mice, monkeys and non-viable human embryos. That fall, visiting Dr Quake, he said: “I want to create the first gene-edited humans,” Dr Quake recalled.

“You must do it carefully,” Dr Quake said he warned him. “Otherwise, it will ruin your scientific career.”

In a 2017 meeting with Dr He, Stanford’s Dr Hurlbut said, “one of the first things he said to me when he sat down was, ‘The people against embryo research in the US, that’s just a fringe, just a fraction, right’’”

The American responded: “Not really, JK,” addressing Dr. He by the initials he uses in emails. “America’s pretty evenly divided on that issue.”

The US government is barred from funding work that involves endangering, destroying, or creating embryos for research, Dr Hurlbut told Dr He.

Such concern about something that hadn’t yet been born was hard to fathom for Dr He, who has two young daughters.

Dr Hurlbut said the Chinese scientist expressed incredulity, asking: “You mean something as small as this is as valuable as my two-year-old daughter?” and pressing his forefinger against his thumb. Dr Hurlbut responded: “That’s the way your little daughter’s life began.”

Dr. He was investigating editing a gene that can offer protection from familial hypercholesterolaemia, a rare cholesterol-related disease that can cause broken bones in children.

He changed his mind after visiting a village where he saw HIV-positive families facing discrimination, people close to him say. Children born to infected individuals weren’t able to attend regular schools. He saw a gene-editing trial as a way to use science against that injustice.

The Wall Street Journal