David Cameron’s payday preceded Greensill Capital’s collapse

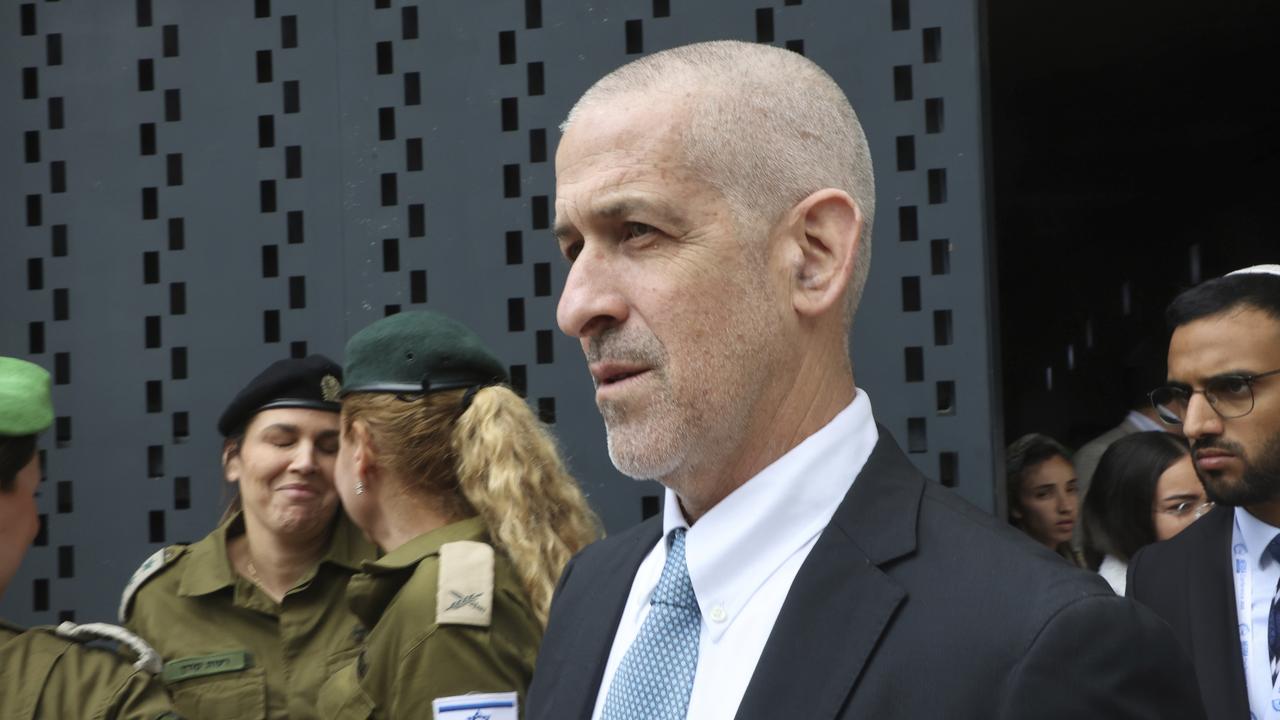

The former British prime minister, who made several million dollars as an adviser to Greensill, will testify before a UK parliament committee on Thursday night.

Former British prime minister David Cameron was looking for his next act after leaving office in the shadow of the Brexit vote in 2016. He found it in Greensill Capital.

He jetted around the world on the specialty finance firm’s private aircraft, lobbying corporate executives and government officials. He earned an annual salary, bonus and cashed out stock options in 2019, bringing him several millions of dollars in total, said people familiar with his compensation.

And then it all fell apart. The company collapsed into bankruptcy in March, stranding $US10bn ($12.8bn) in investor funds. It is under investigation in Britain and Germany. The UK government last month announced a review into contracts it gave to Greensill and Mr Cameron’s lobbying for access to taxpayer funds.

Mr Cameron, who has denied doing anything improper, is set to testify before a UK parliament committee on Thursday night (AEST), a rare instance of a former prime minister being hauled before parliament.

“Much of the reporting around David Cameron’s association with Greensill Capital has not been accurate,” said a spokesman for Mr Cameron. He declined to comment further, adding that Mr Cameron would answer questions at the hearing.

Founded by Australian banker Lex Greensill, Greensill Capital worked in an area known as supply-chain finance, a form of cash advance that lets companies stretch out the time to pay bills. Greensill packaged those cash advances into bondlike securities, which were sold off to investors, mainly through Credit Suisse Group AG investment funds. When Greensill lost a key insurance provider backstopping the assets, Credit Suisse froze the funds, and Greensill plunged into crisis.

Mr Cameron joined as an adviser in 2018. People familiar with Mr Cameron’s role at Greensill said he was a “door-opener” who helped the firm get meetings with government officials and business executives.

Mr Cameron’s lobbying efforts on behalf of Greensill have been particularly contentious in the UK, though many of his interventions don’t appear to have panned out for Greensill.

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit last northern spring, Mr Cameron reached out to British government officials to make sure Greensill had access to a Bank of England emergency financing facility for big companies. The rules stated that finance companies weren’t eligible for the loans.

Mr Cameron sent 56 messages to top British politicians, including the chancellor of the Exchequer, a Downing Street aide and senior UK Treasury officials, over several months seeking to have the rules changed, according to disclosures he made to a parliamentary committee. Treasury officials ultimately rejected the proposals.

Mr Greensill met Mr Cameron in 2011, when the former banker served as a private-sector adviser to Mr Cameron’s government. He was involved enough in operations to carry a government business card with a Downing Street email address. Several senior government officials and civil servants he worked with there later joined Greensill and were granted shares in the company.

In June 2016, after saying he would resign as prime minister in the wake of the Brexit vote, which he campaigned against, Mr Cameron found himself in a void, people who know him say. He would occasionally offer advice to his successor, Theresa May, but was intent on not being seen as trying to influence decisions as the country navigated the Brexit process.

In 2017, Mr Cameron began to set up a UK-China fund to promote commercial ties between the two countries. But as diplomatic tensions between the countries grew, interest in the fund stalled and it wasn’t launched.

British rules prevent former ministers from lobbying the government for two years after leaving their post. Around the time that window expired in 2018, he joined Greensill.

Mr Greensill told a parliamentary committee this week that he hired Mr Cameron shortly after losing out on a major contract with a blue-chip company that didn’t recognise the Greensill name. He said he had hoped Mr Cameron would help with brand recognition in Britain and abroad.

Mr Cameron said in a public statement in April that he was motivated by his “desire to work for a UK-based, entrepreneurial, early stage finance and technology venture, rather than simply work with larger, more well-known financial institutions.”

Mr Cameron believed the firm was credible given that it counted private-equity firm General Atlantic as an investor and had a key relationship with Credit Suisse, while several blue-chip companies were major Greensill clients, the former politician said in a submission to the same committee.

Mr Greensill said in his testimony that Mr Cameron provided “analysis and geopolitical thinking” and regularly attended the company’s board meetings.

In late 2018, Mr Cameron discussed Greensill in a meeting with then-president of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto, according to a person familiar with the matter. State-owned oil giant Petróleos Mexicanos had recently dropped Greensill as a provider of $US3bn in financing.

Mr Cameron also during that period flew to Danbury, Connecticut, to meet with executives from General Electric, which was selling its trade-payables services platform, according to people familiar with the meeting. Greensill was interested in acquiring the business but lost out to Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc.

In 2019, SoftBank Group’s Vision Fund invested nearly $US1.5bn in Greensill, giving Mr Cameron and others inside the company an opportunity to sell some of their options. Some board members at the time raised questions with Mr Greensill about the large size of Mr Cameron’s compensation, said the people familiar with Mr Cameron’s role.

A few months later, Mr Cameron and Mr Greensill networked with business figures at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In Australia, Mr Cameron met with Greensill customers and with executives of a crucial Greensill insurance partner, Mr Greensill said in his testimony. In January last year, Mr Cameron and Mr Greensill visited Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Saudi Arabia, where Greensill hoped to expand its business.

When the pandemic hit, Mr Cameron sent a flurry of text messages to top-level government officials, according to government disclosures.

These showed that on April 3, 2020, he messaged the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak, Minister for the Cabinet Office Michael Gove, a top Downing Street official, two junior Treasury ministers and a deputy governor of the Bank of England asking about rules that blocked Greensill from an emergency lending program.

“Am now speaking to Rishi first thing tomorrow. If I am still stuck, can I call you then?” he texted that evening to Mr Gove. Mr Cameron secured two calls with Mr Sunak. However, the government refused to budge.

In his submission to the parliamentary committee, Mr Cameron said he first became aware that Greensill was in serious trouble in December 2020 following a call from Mr Greensill.

“Up until that point, I firmly believed that Greensill was in good financial health,” he said. “In the autumn of 2020, I understood Greensill was on track for a relatively strong year.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout