Coronavirus triggers global food crisis

Dozens of nations are at risk of famine amid processing and transportation breakdowns and panic buying. A food crisis has emerged when lots of food is available.

The coronavirus pandemic hit the world at a time of plentiful harvests and ample food reserves. Yet a cascade of protectionist restrictions, transport disruptions and processing breakdowns has dislocated the global food supply and put the planet’s most vulnerable regions in particular peril.

“You can have a food crisis with lots of food. That’s the situation we’re in,” says Abdolreza Abbassian, a senior economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN.

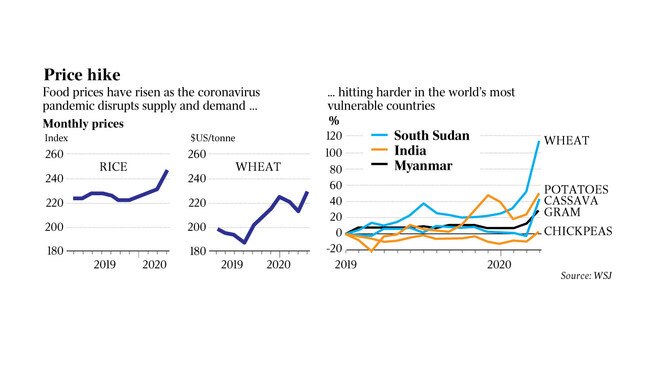

Prices for staples such as rice and wheat have jumped in many cities, in part because of panic buying set off by export restrictions imposed by countries eager to ensure sufficient supplies at home. Trade disruptions and lockdowns are making it harder to move produce from farms to markets, processing plants and ports, leaving some food to rot in the fields.

Dozens of nations face famine

At the same time, more people around the world are running short of money as economies contract and incomes shrivel or disappear. Currency devaluations in developing nations that depend on tourism or depreciating commodities like oil have compounded those problems, making imported food even less affordable.

“In the past, we have always dealt with either a demand-side crisis, or a supply-side crisis. But this is both — a supply and a demand crisis at the same time, and at a global level,” says Arif Husain, chief economist at the UN’s World Food Program. “This makes it unprecedented and uncharted.”

The WFP has warned that up to three dozen nations could face famines by the end of the year, potentially pushing an additional 130 million people to the brink of starvation.

In self-sufficient farming nations such as the US, the fallout so far has been limited. While the variety on supermarket shelves has diminished somewhat, and the meat-processing industry has experienced some interruptions, there are no major food shortages.

Other countries, rich and poor, are facing critical challenges in how to make sure their populations get enough to eat in coming months and years.

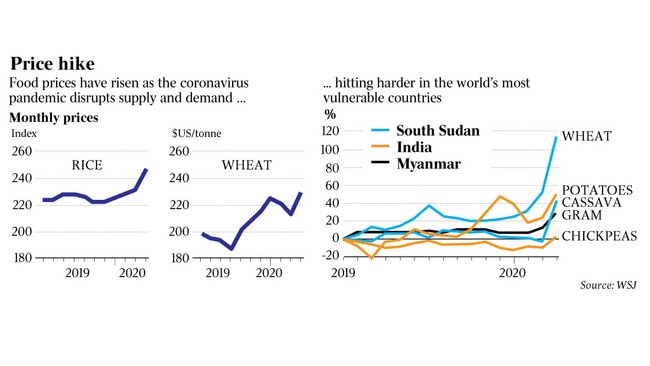

South Sudan, where a new unity government was formed recently to end a long-running civil war, is one of the nations most at risk. Data published by the FAO show that prices for wheat in the capital city of Juba have shot up 62 per cent since February. Prices for cassava, a local staple otherwise known as tapioca, are up 41 per cent.

“I don’t even want to imagine how bad it’s going to be,” said Mabior Garang, the African country’s deputy interior minister-designate. “The borders have been closed, and we don’t have any local production of food in our country. We were already facing a famine pre-corona. If you add corona to the equation, it’s crazy.”

Potato prices are up 27 per cent since February in Chennai, India, according to the FAO data. In Yangon, Myanmar, prices for gram, a type of chickpea, have climbed 20 per cent.

In the Pakistani city of Lahore, van driver Muhammad Asif says his family used to cook chicken twice a week before the pandemic, and mutton once a month. Now, he said, they are eating as little food as possible, subsisting on basic staples as his income declined by 60 per cent, while food prices in local groceries increased by at least 25 per cent.

“The virus has made life very difficult for people like us. If the situation continues like this for another couple of months, people will start snatching food from others and stealing to meet their needs,” Asif says.

Food shortages have caused political upheavals throughout human history. In the years after the 2008 financial crisis, a surge in food prices worldwide helped unleash a wave of turmoil and insurgencies in many parts of the Middle East and Africa. The Arab Spring’s series of rebellions was in part caused by a Tunisian vegetable seller setting himself on fire in 2010. Today, many governments worry that breakdowns of the food supply could inspire similar upheaval.

“Food security is key in maintaining socio-economic and political stability. We can ignore this only at our own risk,” President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, the world’s biggest rice importer, told last month’s summit of Southeast Asian leaders. “Our most urgent priority is ensuring a sufficient supply of rice for our people.”

Lockdown logistical issues

As economies worldwide come out of lockdown, logistical issues could be resolved, borders could start to reopen and food trade would pick up, alleviating some risks. Yet, it is unclear how many months that would take — a variable that depends on the future course of the pandemic itself.

The biggest danger going forward, economists say, is that the pandemic’s dislocations will affect not just existing food stocks but planting and harvesting in coming months. That already is occurring in parts of the world, just as a swarm of locusts is eating its way across swathes of Africa and Asia.

In India, which has been under a nationwide lockdown since March 25, Minati Swain’s crop of tomatoes and bananas went to waste in the fields last month because restrictions on movement made it impossible to get the produce to local markets in the eastern state of Orissa. Then, heavy rains destroyed the 33-year-old farmer’s remaining crop of eggplant.

“Now, we don’t even have money to buy food from the market,” she said. “And if there is no money, how can we plant for the next season?”

Around the world, shipping disruptions have made it prohibitively expensive or impossible to move many perishable items, especially fruits, vegetables and fish, from producers to consumers.

Between January 1 and April 10, the capacity of container ships moving goods fell 30 per cent because of cancelled sailings. Those that do reach ports face new delays due to quarantines and shutdowns of customs and other facilities in many places. Sometimes that results in spoiled cargoes.

About 85 per cent of passenger flights worldwide have been cancelled, reducing global air-cargo capacity by about 35 per cent, according to the consulting firm McKinsey.

Exports restricted

India is the world’s biggest exporter of rice, helping feed nations across Africa and Asia. These days, New Delhi-based rice exporter Shri Lal Mahal Group is shipping only 15 per cent to 20 per cent of its normal volume.

“There is plenty of rice in India,” says company Chairman Prem Garg. “It’s just that we can’t export it because of logistics issues.”

Among the obstacles: While there used to be an available vessel to European markets every two or three days, now there’s just one every two weeks.

Some of the other top 10 rice-selling nations compounded the disruptions with export restrictions. Vietnam, the world’s third-largest rice exporter, stopped all shipments in March. Myanmar and Cambodia also imposed curbs.

The world’s biggest wheat exporter, Russia, last month halted exports until July. Major wheat suppliers Romania, Ukraine and Kazakhstan also capped sales. Turkey restricted the export of lemons, Thailand of chicken eggs, Serbia of sunflower seeds.

Though some restrictions have since been relaxed, and Vietnam is resuming rice exports, this threat of protectionism has fuelled a global rise in prices for some staple commodities despite bumper crops. Thai rice was up 14% in April, reaching a seven-year high. Black Sea wheat is up 7 per cent. Though global prices for feed grains are down, that is largely because of problems in the meat industry.

Hoarding vital staples

Amid this uncertainty, major food importers are responding by hoarding vital staples, which could further drive up prices.

Egypt, the world’s biggest wheat importer, rarely purchases foreign wheat during its own harvesting season, which is now under way. Yet, last month, it bought large quantities of French and Russian grain, part of Cairo’s new plan to stockpile up to eight months’ worth of reserves. Those transactions, traders said, helped drive up global wheat prices.

“If you ask governments what they want to do, they want to accumulate stocks, which is a big problem because, first, the price will be lower tomorrow, and, second, they don’t have the capacity to manage them properly,” says Maximo Torero Cullen, chief economist at the FAO.

Wealthier importers such as Japan, Taiwan and the United Arab Emirates can outbid poorer countries that already face shortages. It is in these poorer nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, that food inflation is hitting the hardest.

Nigeria is home to 200 million people and one of the world’s largest rice and wheat importers. It is suffering from the combined shocks of more expensive imports, disruptions of local production and transport, and the collapse of global prices for its main export, oil.

Haresh Keswani, whose Artee Group operates 15 SPAR hypermarkets across Nigeria, says he had to shut down five outlets because he couldn’t get enough inventory or workers.

“The farmers have increased the prices of food products because of the lockdown and the lack of access to their farms, and we the buyers are now at the receiving end,” says Sadiq Usman a labourer in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. “It’s not been easy feeding my family, and now we’re eating just once a day.”

Some of the world’s wealthier food importers have been preparing for disruptions since the previous crisis a decade ago. Taiwan, which imports two-thirds of its calorie needs, has amassed 900,000 metric tonnes of rice in a government stockpile, three times the amount its Council of Agriculture is legally mandated to have. Those stocks were built up before the pandemic.

Now, Taiwan says its farmers will produce an additional 1.2 million metric tonnes in the next six months, leaving it with enough rice reserves to feed its population for 21 months.

The UAE imports some 90 per cent of its food. A network of 105 Carrefour grocery stores there increased its stock from three months to four because of the pandemic, says Alain Bejjani, chief executive of Dubai-based Majid al-Futtaim Group, which operates 300 Carrefour outlets in 16 nations. He says retailers and the government are in talks on how to boost stocks of key items to as much as 12 months — something that would require major investments in storage and inventory.

That kind of stockpiling would be impossible in Nigeria, says Keswani, the supermarket executive based in Lagos. As a result, Nigerian supermarkets often have bare shelves these days. Just 26 per cent of Keswani’s orders are being filled by suppliers, down from more than 90 per cent before the pandemic.

“Suppliers either don’t have the goods, they are not manufacturing, or they don’t know how to get the goods to us,” he says. “What is not getting through is a huge list. Are the fruits and vegetables getting through? No. Are the meats getting through regularly? No. There is not enough.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout