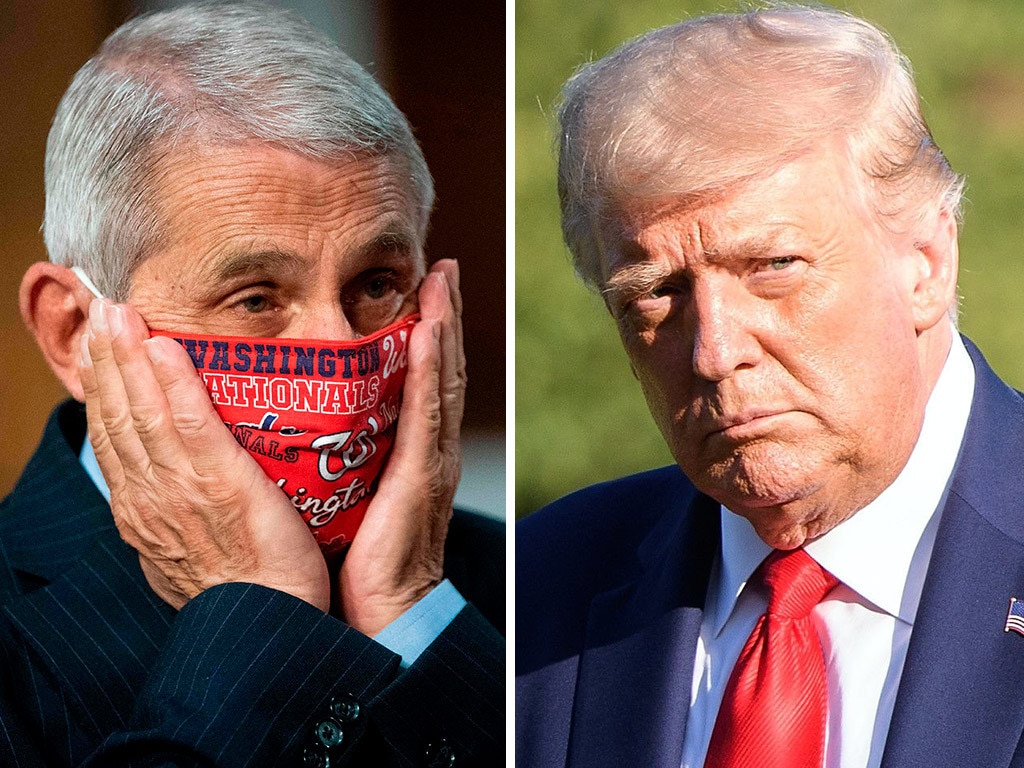

Coronavirus: hyroxychloroquine and US politics

Neither man has any expertise in pharmacology, and Mr Trump did get out over his skis in promoting the malaria treatment, also known as HCQ, for the novel coronavirus. But since every Trump action prompts a reaction, his political and media opponents launched a campaign to discredit the drug. This politicised environment has produced dubious science and erratic policy.

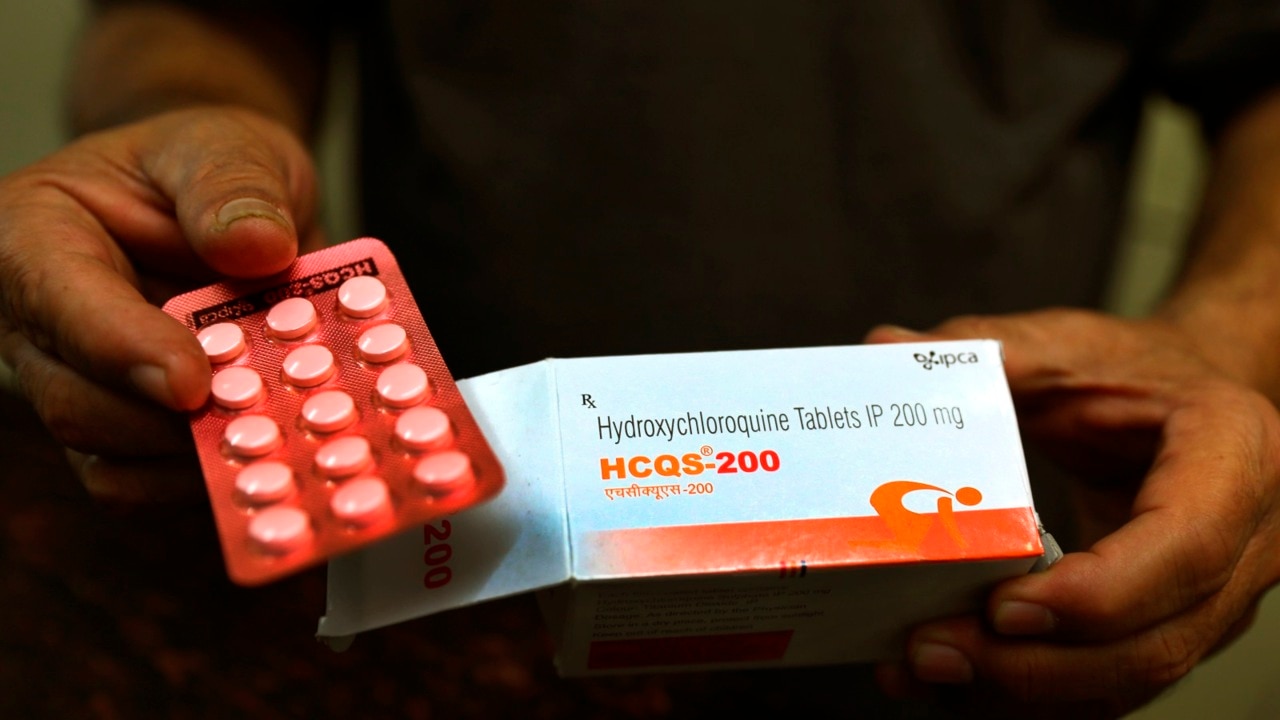

The Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorisation on March 28, allowing hospitals to treat COVID-19 patients outside clinical trials using HCQ donated by manufacturers to the national stockpile. But on June 15 the agency rescinded the authorisation. “In light of ongoing serious cardiac adverse events and other potential serious side effects,” the FDA announced, “the known and potential benefits of … hydroxychloroquine no longer outweigh the known and potential risks for the authorised use.”

But the scientific basis for the revocation now appears faulty. Most studies didn’t adjust results for confounding variables such as disease severity, drug dosage or when patients started treatment. Two new peer-reviewed studies find that HCQ can significantly reduce mortality in hospitalised patients. With hospital beds filling up across the American South and West and a limited supply of Gilead Sciences ’ antiviral remdesivir, the FDA should reinstate its emergency-use authorisation for HCQ.

HCQ has been safely used for decades to treat patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, both inflammatory auto-immune conditions. The drug has also been found to interfere with the novel coronavirus’s replication in vitro, and studies this spring from France, Brazil and China showed the drug might help moderately ill patients.

HCQ also has side effects. It can cause cardiac arrhythmias, a particular risk for severely ill COVID-19 patients because the virus can damage heart tissue. But the FDA emergency authorisation warned about this and required doctors to monitor patients closely and report adverse side effects to the agency.

In late May, the Lancet published a large-scale international study that claimed hospitalised COVID-19 patients treated with HCQ were 30% more likely to die. But the medical journal retracted the study on June 4 after more than 120 scientists pointed out significant flaws in the data and methodology. The source of the raw data refused to share it with independent reviewers.

Nonetheless, the anti-Trump media claimed vindication later that day when the New England Journal of Medicine published a randomised trial that concluded HCQ didn’t prevent illness in people who had been exposed to the virus. The study’s raw data showed that people who took HCQ within two days of exposure were 38 per cent less likely to develop symptoms. But a third of subjects in the trial took the drug four days after exposure, which obscured its benefits. Since the average viral incubation period is five days, starting the drug four days after exposure is unlikely to do much good.

On June 5, University of Oxford researchers reported that a midpoint review of their HCQ trial had found no clinical benefit. “This result should change medical practice worldwide,” Oxford epidemiologist Martin Landray declared in a press release. It usually pays to be sceptical of such sweeping claims based on a single study.

The Oxford team released a preprint study with more data from its trial on Wednesday. Patients were treated on average nine days after their symptom onset, which may have been too late to improve clinical outcomes. The trial’s protocol also called for dosages two to three times as high as those recommended by the FDA’s emergency use authorisation.

In revoking the authorisation 10 days later, the FDA cited the New England Journal and Oxford work as well as a British Medical Journal study from China that purportedly found no benefit from the drug. Yet an April draft of the last study concluded that HCQ accelerated “the alleviation of clinical symptoms, possibly through anti-inflammatory properties” and “might prevent disease progression, particularly in patients at higher risk.”

The draft also noted that after adjusting for the confounding effects of other antivirals used to treat patients, “the efficacy of HCQ on the alleviation of symptoms was more evident.” This analysis of HCQ’s benefits was scrubbed from the published version because some editors and reviewers quibbled that it wasn’t called for in the trial protocol.

The first of the new studies showing benefits from HCQ appeared in the Journal of General Internal Medicine on June 30. It found patients treated with the drug at New York’s Mount Sinai Health System hospitals were 47 per cent less likely to die after adjusting for confounding variables such as underlying health conditions and disease severity. Notably, Mount Sinai’s treatment protocol called for lower dosages than in the Oxford trial, and patients on average were treated within one day of hospitalisation.

The second, published July 1 in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, found that patients treated with HCQ at Henry Ford Health System hospitals in Detroit were 50 per cent to 66 per ent less likely to die after adjusting for confounding variables including other treatments. Nearly all patients began treatment within two days of admission, received dosages that hewed closely to FDA guidelines, and were continuously monitored for cardiac arrhythmias.

“Our patient population received aggressive early medical intervention, and were less prone to development of myocarditis, and cardiac inflammation commonly seen in later stages of COVID-19 disease,” the Henry Ford doctors noted.

This shouldn’t be surprising. An FDA safety review published July 1 reported only five adverse side effects from HCQ through the emergency use authorisation among tens of millions of doses that were distributed to hospitals. This suggests that the drug isn’t harmful to the vast majority of patients who are treated according to FDA guidelines.

With hundreds of Covid-infected Americans still dying each day, the agency should let physicians decide whether to treat patients with HCQ based on their experience and scientific evidence. Leave politics out of it.

The Wall St Journal

Hubert Humphrey began his career as a pharmacist before going into politics. Today’s politicians sometimes seem to have the opposite aspiration. President Trump “pushes dangerous, disproven drugs,” Joe Biden declares in his “Plan to Beat COVID-19.” “Our country is now stuck with a massive stockpile of hydroxychloroquine, a drug Trump repeatedly hailed.”