Coronavirus exposes Apple’s dependency on China

Long before the coronavirus struck, Apple’s operations team began raising concerns about the giant’s dependency on China.

Long before the coronavirus struck, Apple’s operations team began raising concerns about the technology giant’s dependency on China.

Some operations executives suggested as early as 2015 that the company relocate assembly of at least one product to Vietnam. That would allow Apple to begin the multi-year process of training workers and creating a new cluster of component providers outside the world’s most populous nation, sources said.

Senior managers rebuffed the idea. For Apple, weaning itself off China, its second-largest consumer market and the place where most of its products are assembled, has been too challenging.

Apple’s reliance on China has long frustrated staff — and more recently unnerved investors. The coronavirus represents Apple’s third major setback there in as many years, including the fallout from tensions with the US that included tariffs and slower-than-expected iPhone sales in the country.

Factory production has been crippled as China has shut down activities and sought to contain the outbreak, and Apple warned investors it would not meet its own sales estimates in the current quarter. Since that warning, Apple’s market value has declined by more than $US100bn ($152.6bn).

“No executive will admit in a public forum: we should have thought about” the vulnerability to China, said Burak Kazaz, a Syracuse University supply chain professor and former researcher at IBM. “But from this point on, there are no excuses.”

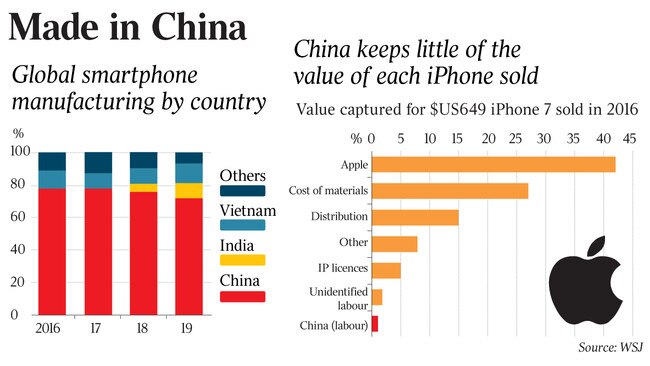

China has been a critical factor in Apple’s soaring market value. The nation provides a stable, efficient, low-cost manufacturing base with an abundant network of suppliers that have helped cement Apple’s profitability.

Apple chief executive Tim Cook continues to play down the need to significantly change Apple’s supply chain. During an interview on Thursday with Fox Business Network, he said unpredictable events were a facet of modern business and noted that Apple’s operations team had previously navigated earthquakes, tsunamis and other challenges.

“The question for us is: was the resilience there or not? And do we need to make some changes?” Mr Cook said.

“My perspective sitting here today is that if there are changes, you’re talking about adjusting some knobs, not some sort of wholesale fundamental change.”

Apple has recently started to experiment with small production moves out of China. These attempts, including plans to assemble wireless earbuds in Vietnam and produce iPhones in India and Mac Pro computers in the US, have laid bare a number of difficulties.

A clean break with China is impossible. Apple relies on a workforce of more than three million indirect workers in China. Its top manufacturer, Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology, hires hundreds of thousands of seasonal employees in China, many of whom manually insert tiny screws and thin printed circuit boards during the iPhone assembly process. Tens of thousands of experienced manufacturing engineers oversee the process.

Finding a comparable amount of unskilled and skilled labour was impossible, said Dan Panzica, a former Foxconn executive. The population in China has allowed suppliers to build factories with a capacity for more than 250,000 people. The number of migrant workers in China, who do much of Apple’s production, exceed Vietnam’s total population of 100 million. India is the closest comparison, but its roads, ports and infrastructure lag far behind those in China.

“You’re not going to be able to have mega-factories anywhere else,” Mr Panzica said. “You’re going to have to break them up.”

Moving out could also jeopardise Apple sales in China, which counts for nearly a fifth of its total revenue. Employing so many local workers helped the company gain access to the market and any reduction might weaken its standing with the government, which wields tremendous influence over how global brands are perceived, according to Neil Mawston, a technology researcher with the firm Strategy Analytics.

Though Apple’s brand remains strong in China, its share of the smartphone market has declined to 7.5 per cent, from a peak of 12.5 per cent in 2015, because of pressure from homegrown rivals such as Huawei, according to Canalys, a market research firm.

Mr Cook, who joined the company in 1998, is the architect of Apple’s China business. As head of operations, he assumed responsibility for a company saddled with extra inventory and reliant on its own US manufacturing plants. Following the practices of Dell, Compaq and other computer brands, he started outsourcing to contract manufacturers in Asia.

Around 2000, he met Foxconn founder Terry Gou, who would become the dominant contract manufacturer in Asia. Foxconn struck deals to be one of the few manufacturers of iPods, which made its debut in 2001, and an early maker of the iPhone, which launched in 2007.

Beijing was supporting tech manufacturing because it wanted its factories to make more sophisticated products rather than plastic toys and clothes. In 2001, Apple officially entered China with a Shanghai-based trading company.

As iPhone sales surged, Apple, Foxconn and China scrambled to meet the demand. In 2010, China took over farmland in Zhengzhou, and within months, a Foxconn factory complex was built for 250,000 workers. The government also has helped funnel workers to Foxconn, posting notices online.

Over time, Apple, Foxconn and China formed a triangle of interdependency. Apple grew to depend on Foxconn to make devices and Chinese consumers to buy them. Foxconn built its business by leaning on China’s vast workforce and control over land to construct factories. And China became beholden to Foxconn as the nation’s largest private-sector employer and Apple as a trainer of new technology suppliers.

Apple is unlikely to shift any of the production of its most expensive iPhones to India later this year. The supply chain isn’t in place, and workers in India aren’t ready to produce the high-end, organic light-emitting diode models, a source said. Foxconn didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Efforts to restart production in the US have also hit snags.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout