China’s global mega-projects are falling apart

Many of China’s Belt and Road infrastructure projects are plagued with construction flaws, including a giant hydropower plant in Ecuador, adding more costs to a program criticised for leading countries deeper into debt.

Built near a spewing volcano in San Luis, it was the biggest infrastructure project ever in Ecuador, a concrete colossus bankrolled by Chinese cash and so important to Beijing that China’s leader, Xi Jinping, spoke at the 2016 inauguration.

Today, thousands of cracks have emerged in the $4bn Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant, government engineers said, raising concerns Ecuador’s biggest source of power could break down. At the same time, the Coca River’s mountainous slopes are eroding, threatening to damage the dam.

“We could lose everything,” said Fabricio Yépez, an engineer at the University of San Francisco in Quito who has closely tracked the project’s problems. “And we don’t know if it could be tomorrow or in six months.”

It is one of many Chinese-financed projects around the world plagued with construction flaws.

During the past decade, China handed out a trillion dollars in international loans as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, intended to develop economic trade and expand China’s influence across Asia, Africa and Latin America. Those loans – totalling as much as the rest of the world combined – made Beijing the largest government lender to the developing world, according to the World Bank.

Foreign leaders, economists and others say the program has contributed to debt crises in Sri Lanka and Zambia, and that many countries have limited ways to repay the loans. Some projects have also been called mismatches for a country’s infrastructure needs or damaging to the environment.

Now, low-quality construction on some of the projects risks crippling key infrastructure and saddling nations with even more costs for years to come as they try to remedy problems.

“We are suffering today because of the bad quality of equipment and parts (in Chinese-built projects),” said René Ortiz, Ecuador’s former energy minister and ex-secretary general of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. China’s embassy in Ecuador wouldn’t comment.

Chinese money has been used to build everything from a port in Pakistan to roads in Ethiopia and a transmission line in Brazil.

Chinese construction companies often bid for government projects or directly approach local officials with projects with a promise they can easily arrange financing packages from Chinese banks and insurers.

That, developing-country officials say, has given Chinese companies a leg-up, because it means governments eager to build a new dam or road don’t have to drum up their own funding. Critics say the relatively easy availability of Chinese loans for Chinese construction can lead to inflated project costs because there is less pressure on governments to minimise expenses.

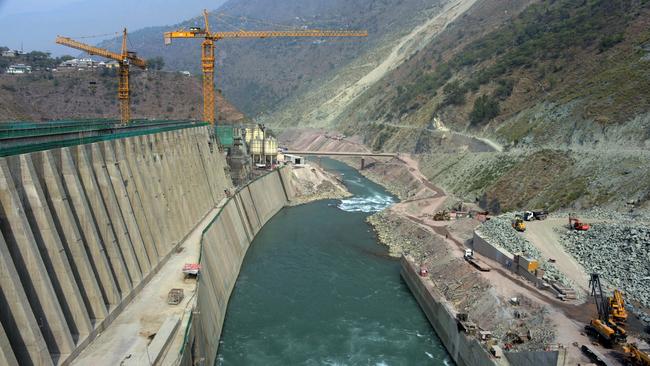

In Pakistan, officials shut down the Neelum-Jhelum hydroelectric plant last year after detecting cracks in a tunnel that transports water through a mountain to drive a turbine. The head of the country’s electricity regulator, Tauseef Farooqui, told Pakistan’s Senate in November that he was concerned the tunnel could collapse just four years after the 969-megawatt plant became operational. That would be disastrous for a nation that has been battered by rising energy prices, said Farooqui. The closure of the plant is reportedly costing Pakistan about $44m a month.

Hydropower plants can have operating lives of up to 100 years, according to the World Bank.

Uganda’s power generation company said it has identified more than 500 construction defects in a Chinese-built 183-megawatt hydropower plant on the Nile River that has suffered frequent breakdowns since beginning operation in 2019. China International Water & Electric Corp, which led construction of the Isimba Hydro Power Plant, failed to build a floating boom to protect the dam from water weeds and other debris, which has led to clogged turbines and power outages, according to the Uganda Electricity Generation Co. There had also been leaks in the roof of the plant’s power house on to the generators and turbines. The plant cost $800m and was financed mostly through a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China.

Completion of another Chinese-built hydropower plant further down the Nile, the 600-megawatt Karuma Hydro Power Project, is three years behind schedule, a delay Ugandan officials have blamed on various construction defects, including cracked walls. UEGC also said the Chinese contractor, Sinohydro Corp, installed faulty cables, switches and a fire extinguishing system that need to be replaced. Earlier this year, the government had to start paying back the $2bn it borrowed from the Export-Import Bank of China to finance the inoperational project. Sinohydro and China International Water didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In Angola, 10 years after the first tenants moved into Kilamba Kiaxi, a vast social housing project outside the capital, Luanda, many locals are complaining about cracked walls, mouldy ceilings and poor construction.

The project, built by China’s CITIC Group, was initially funded through a $3.5bn, oil-backed credit line from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China that was later refinanced by the China Development Bank, according to William & Mary’s Aid Data Research Lab.

“Our building has a lot of cracks,” said Aida Francisco, who lives in a four-bedroom apartment in Kilamba with her husband and three sons. Like many other middle-class families in Kilamba, she is purchasing the apartment through a rent-to-buy program. Humidity collects in the apartment’s walls, causing mould, Francisco said, and a lot of the building materials, including doors and railings, are of poor quality.

When she moved to Kilamba in 2016, Francisco said, Chinese contractors still came to fix problems. But in recent years many buildings, including hers, have fallen into disrepair, especially as many tenants, who are responsible for the upkeep, lost their jobs amid Angola’s economic crisis.

“If you see these buildings, they won’t last long,” said Francisco. “They’re falling apart bit by bit.”

A spokeswoman for CITIC said humidity issues in a small number of units in Kilamba were due to tenants making improper renovations and the company had completed required maintenance.

The Chinese government didn’t respond to requests for comment on criticism of Chinese-built infrastructure in Africa and Asia; neither would a spokesman for Angola’s Ministry for Construction and Public Works.

In Latin America, Ecuador was at the forefront of Beijing’s push into the region, with Quito accessing more in loans than any country except two much bigger nations, Venezuela and Brazil, according to the Inter-American Dialogue think tank.

After a 2008 sovereign debt default, then president Rafael Correa, a leftist who during his tenure from 2007 to 2017 often clashed with the West and railed against multilateral lenders, turned to China to finance a surge in public spending. In total, Chinese banks lent Ecuador $26bn during Correa’s term.

Ecuadorean lawmakers, former government ministers and anti-corruption activists say the loans lacked transparency, with contracts given to companies without public bids, resulting in shoddy construction, high costs and graft.

In the recent letter published on the Chinese embassy in Ecuador’s Twitter account, it said the financing was agreed on during friendly negotiations with Ecuador and fully complies with laws and regulations in both countries. Ecuadorean officials and economists said some projects made little sense, including the expropriation of farmland in an Andean valley to build a new metropolis called Yachay City that was supposed to turn Ecuador into a regional tech power. The project has been abandoned, with a $9m supercomputer that was supposed to be used by researchers sitting out of doors and unused.

In 2019, the comptroller-general’s office reviewed the construction of 200 Chinese-built schools, reporting some of the buildings had problems with their foundations and others had classrooms with sloping floors and exposed cables.

Correa was convicted in 2020 of corruption charges and lives in exile in Belgium.

China’s most ambitious project in Ecuador was Coca Codo Sinclair, which Ecuadorean engineers first studied for the Coca River in the 1970s. Back then, they considered it a risky venture due to its steep cost and location near an active volcano.

But Ecuador wanted the dam to improve an electrical grid that regularly suffered blackouts and relied on costly energy imports. Today, it supplies about a third of Ecuador’s electricity.

During Correa’s term, the China Development Bank agreed to finance 85 per cent of Coca Codo Sinclair’s initial cost, with a 6.9 per cent interest rate. Sinohydro carried out the construction and flew in hundreds of Chinese workers to build the plant.

The China Development Bank and Sinohydro did not respond to requests for comment.

In September, prosecutors searched the office of Sinohydro over allegations it paid bribes to people close to Correa when the contract was awarded to the Chinese firm. No one has been charged in that ongoing investigation.

Some engineers questioned the project early on, saying the environmental studies were out of date. The plant’s 1500-megawatt capacity was much larger than that originally envisioned, adding to costs and creating more capacity than the river could power, according to former energy officials and congressional investigators. In 2014, 13 Chinese and Ecuadorean employees were crushed to death in a construction accident.

Since the 2016 opening, officials from the state electricity utility have found more than 17,000 cracks in the power plant’s eight turbines, according to the state utility. It blames the fissures on faulty steel imported from China. In 2021, the utility took Sinohydro to international arbitration in Chile, which is ongoing, over demands to repair the damage.

President Guillermo Lasso’s government has refused to officially take over management of the plant from Sinohydro, as was planned at the completion of construction, until the cracks are repaired. Numerous attempts to fix the cracks have failed, utility officials said.

“Over my dead body will I accept this poorly built plant,” Energy Minister Fernando Santos told local media in November.

In San Luis, locals such as Adriana Carranza got jobs with Sinohydro, which hired her to cook for Chinese workers. They were 14-hour days, but the job allowed her to save enough to build a house for her family, she said. At home, she still cooks sweet-and-sour chicken and other Chinese dishes.

But in 2020, the Coca River’s slopes began collapsing, creating thunderous crashes and rattling the ground like an earthquake. The erosion destroyed Ecuador’s biggest waterfall. It took out a stretch of a key road and oil pipeline. Carranza said a neighbour’s home went over the cliff.

Fearing for her own home, Carranza fled San Luis last year, salvaging what she could from her house, taking windows, doors and even the roof. “I became deeply depressed, I couldn’t get out of bed. We’ve lost everything.”

Ecuador’s state utility said the erosion is a natural phenomenon in an area prone to natural disasters. Some geologists agree, but others blamed Coca Codo Sinclair, saying its concrete structures so disrupted the river’s natural flow and accumulation of sediments that the fast-moving water began to cut into the river banks as it descended from the Andes.

“The erosion is a process that would normally occur over thousands or millions of years, but the dam has accelerated it in a matter of just five,” said Carolina Bernal, a geologist at the National Polytechnic university in Quito.

They tried to stop the erosion by placing shipping containers in the water to slow the current. These were washed away.

Nancy Chicaiza, a San Luis resident, has little hope for its survival. She believes the erosion will wipe San Luis away.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout