China accepts the new Indo-Pacific reality

While Mr. Xi’s decision to re-engage with the US doesn’t mean he is abandoning his long-term goal of reasserting Chinese primacy in the region and beyond, it is significant. Mr. Blinken hasn’t backed away from such Biden administration policies as imposing controls over tech exports and outbound investment or strengthening defence ties with countries in China’s front yard. Mr. Xi’s meeting with Mr. Blinken indicates that the Communist Party is reluctantly accepting the new status quo rather than freezing relations and confronting the US at every turn to force the Biden administration to change course.

China’s policy making isn’t transparent, but reasons for Mr. Xi’s willingness to engage aren’t hard to find. The Chinese economy is far from robust, and access to foreign investment, technology and markets remains critical to its success. Beijing’s efforts to drive a wedge between European nations and the US have achieved limited results, in part because of Europe’s shocked response to China’s support for Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. A Chinese rejection of Mr. Blinken’s offer of bilateral talks on climate change and trade relations would have further alienated Europe and isolated Beijing.

China also hasn’t had much luck at disrupting America’s growing network of security cooperation in the region. Alarmed by Chinese sabre-rattling and heavy-handed diplomacy, traditional American allies like Japan, Australia and South Korea and important new partners like India are beefing up defence budgets and strengthening their ties with the US Last month’s agreement with Papua New Guinea will give the US access to six sites in the strategically located, mineral-rich island state. Another Pacific island nation, Palau, has asked for American help in fending off aggressive behaviour by Chinese ships.

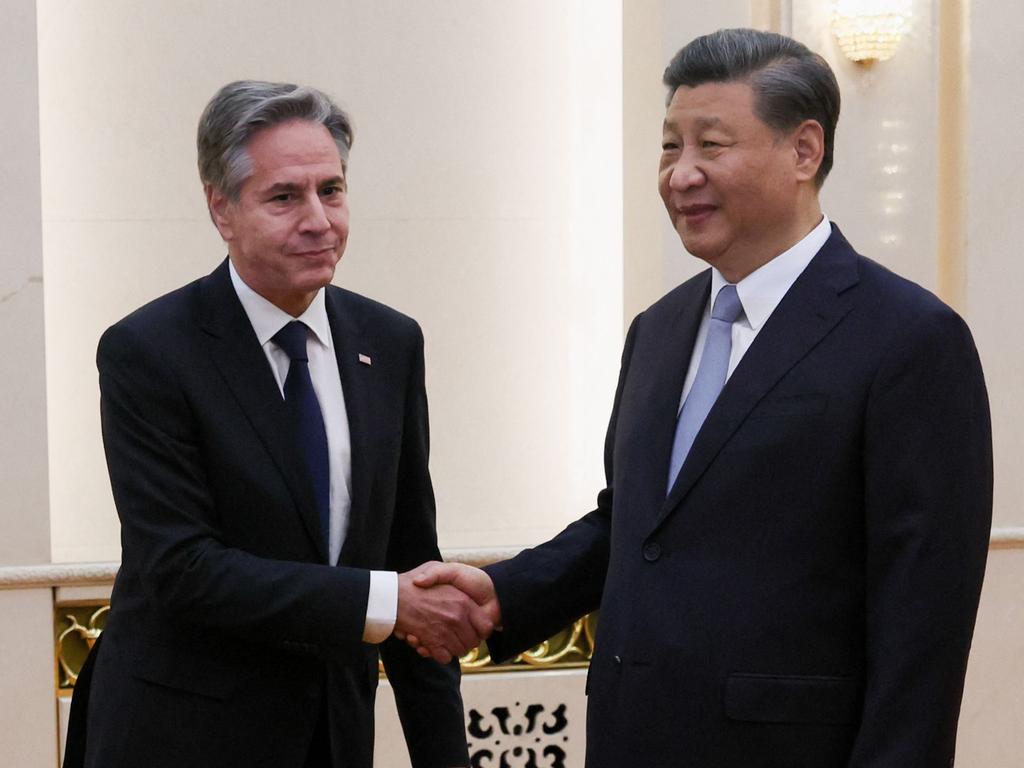

These partners welcome America’s focus on the region but don’t want competition to get out of hand or disrupt the regional economy. Given these concerns, Mr. Blinken’s mission to Beijing was shrewd. It demonstrated to American allies and swing states in Asia that Washington wants to limit and manage the consequences of US-China competition. If Mr. Xi refused to shake Mr. Blinken’s outstretched hand, Beijing would be held responsible for any further deterioration in the regional environment.

Under the circumstances, and with China also concerned about Mr. Xi’s reception if he attends the Asia-Pacific economic summit in San Francisco in November, Beijing has sensibly chosen the path of least resistance. The result is a limited but welcome thaw in an increasingly chilly relationship. Serious problems remain. China rejected Mr. Blinken’s request to reopen military-to-military communication channels that US officials believe are necessary to avoid crises in the seas and airspace around China.

Mr. Blinken’s visit demonstrated the importance of an old truth in diplomatic relations: It is always better to negotiate from a position of strength.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization so far has weathered the storm of Russian aggression in Ukraine. The US-India relationship is going from strength to strength. Japan and South Korea have moved to ease their often-strained relationship. The American-led campaign to limit Chinese access to sensitive computer technology is chalking up important wins. Passage of the flawed but consequential inflation-reduction and semiconductor laws demonstrated America’s economic resilience and, along with the recent debt-ceiling agreement, refuted claims that Washington is hopelessly gridlocked.

These trends are creating a new reality in the Indo-Pacific, and Beijing’s leadership is smart and pragmatic enough to adapt. So far, so good, and Americans in both parties should applaud the Biden administration’s successes across the region.

But the alliances and partnerships that give the US the strength to manage its relationship with Beijing depend on military heft and the depth of economic relationships with other leading powers. American military spending remains woefully inadequate, and the Biden administration has no serious trade strategy. Until these critical gaps are addressed, the edifice of American power the administration hopes to erect in the Indo-Pacific rests on a foundation of sand.

It’s been a good week for the Biden administration’s diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific. As Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares for his visit to Washington, officials in both countries indicated that they have reached important agreements on deepening cooperation. Meantime, Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing was a solid though limited success. Chinese President Xi Jinping signalled that high-level US-China discussions are back on track and that China shares the Biden administration’s interest in stabilising the relationship between the world’s two leading powers.