Can Hollywood’s most troubled awards show be saved?

The controversy-plagued Golden Globes are back on Monday with new prizes and an array of stars but needing more viewers. Ratings for awards shows have plummeted.

Everything you need to know about the rebirth of the Golden Globe Awards – and the stakes for the fast-changing entertainment industry – can be summed up by one of its new categories: a prize explicitly reserved for the movies that made the most money.

Golden Globes officials are calling it the cinematic and box-office achievement award.

It pits eight films that have made at least $US150 million ($224m) against each other, ensuring that the biggest movies that regular people have actually paid money to see – among them John Wick: Chapter 4, Barbie and Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour – are front and centre at an awards ceremony on Sunday night US time, or Monday about midday AEDT.

Two years ago, the Golden Globes were on the edge of extinction. The ceremony had been brought to its knees after a Los Angeles Times investigation painted a picture of a highflying organisation that required studios to entice Globes voters with lavish meals and junkets at five-star hotels, then picked the winners in a way that lacked transparency.

The NBC network refused to air the ceremony that year. The awards were announced via Twitter.

In 2023, the Globes were back for one more go on the network. The ratings were down 26 per cent and viewership hit a near-record low. Last June, the mysterious nonprofit behind the awards disbanded and sold off the show.

Now new owners are attempting a comeback, returning to television Sunday night with new prize categories, new voters and a new network: CBS.

The number of nominees has been increased. More celebrities than ever before, from athletes to pop stars, are on the guest list.

The Oscars, the Globes, the Screen Actors Guild awards and their ilk were once the beating heart of the global entertainment industry, an annual demonstration of the power, stars and money that made the industry a gold mine of cultural and financial influence.

But that world is in danger of disappearing. Streaming blew up the business, ratings for live awards shows plummeted and the industry’s recovery from a pandemic shutdown was stymied by two historic strikes.

Into this chaos comes the ambitious bid to turn around the Globes, once one of the glitziest awards shows. By Monday, Hollywood will know whether the effort has succeeded. If it falls short, the next question may be: Are Hollywood’s other awards shows doomed to irrelevance too? Does Hollywood itself still carry the glamour and the influence that for a century made it a global force?

The Globes have long been considered the unofficial kickoff to award season: a star-studded, boozy dinner party that offered stars and films a chance to lift their profiles on their way to the more prestigious Academy Awards, which take place two months later. That it handed out awards for television effectively doubled the wattage.

Hosts like Ricky Gervais or Tina Fey and Amy Poehler mocked the Globes’ own voters and nearly every star in sight. Its most memorable moments were often the goofiest: Jack Nicholson announced during a rambling acceptance speech that he’d taken a Valium. Brad Pitt thanked a diarrhoea medication. Renée Zellweger was in the bathroom when she was named best actress.

It was a place for attention-grabbing stunts: In 2017, Andrew Garfield playfully pulled Ryan Reynolds in for an on-camera kiss after Reynolds lost an award to Ryan Gosling.

It was also perceived as the least serious award show, dogged by accusations that the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the group of overseas journalists that ran the awards, tended to favour the talent that catered most to its roughly 90 voters by showing up to HFPA parties or offering on-set visits. The motion-picture academy, which hands out the Oscars, currently counts around 10,000 voting members.

The number of Globes voters was so small that every vote carried undue weight, while members’ identities were kept private. The issues were compounded by revelations that the organisation had no Black members, which followed a year when the Globes featured very few Black nominees, despite a plethora of well-regarded movies and TV shows from Black creators. (At the time, an HFPA spokeswoman told The Wall Street Journal that no Black voters had applied in recent years.)

Celebrities boycotted the 2022 ceremony and NBC cancelled the show, which reduced that year’s ceremony to a series of Twitter posts announcing winners. Tom Cruise even returned his three previous Golden Globes in protest.

The ceremony made a cautious return to television last year. The host, comedian Jerrod Carmichael, delivered an introspective monologue about acting as “the Black face of an embattled organisation”. The industry seemed back on board, satisfied with behind-the-scenes changes – at least enough to take advantage of the promotional oomph that the Globes once offered.

But last year’s audience was a mere 6.3 million, down from 18 million in 2020, before mounting problems crashed the Globes’ organising body. By June, the HFPA had disbanded, and its prize asset, the award show, got scooped up by a for-profit joint venture controlled by billionaire Todd Boehly and media impresario Jay Penske.

The latest phase of the comeback has been a scramble.

The Globes’ new owners had to shop this year’s ceremony around until CBS eventually picked it up – paying a significantly lower licensing fee than the roughly $US60m NBC used to pay, according to a person familiar with the situation.

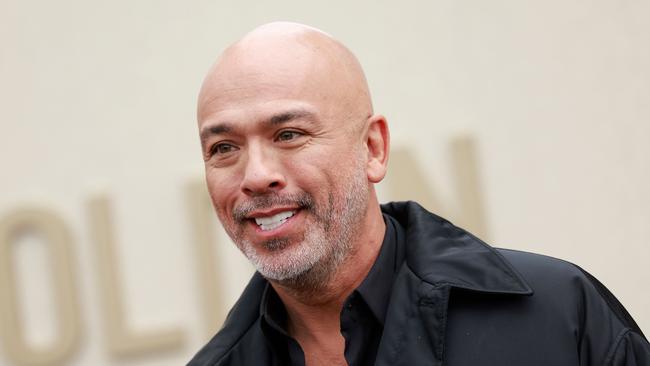

This year’s host, Jo Koy, didn’t know he had the gig until the day it was announced in late December – giving him a few weeks to prepare, rather than the months past hosts had.

“The timeline that we are having right now is crazy,” Koy said in an interview this past week.

The effort to reboot the Globes includes two new prize categories: the blockbuster award and another for stand-up TV comedy, both of which will bring in crowd-pleasing names that wouldn’t usually attend. Most categories went to six nominees, from five.

The owners added new voters, expanding to 300 entertainment-journalist voters from 75 countries. Some were previously members of the HFPA, which ran the Globes for 79 years. Under the organisation’s new code of conduct, voters are not allowed to accept gifts or promotional items and are required to disclose any potential conflicts of interest.

Winners and presenters are to receive a combined $US500,000 worth of gifts, including a five-day stay on a luxury yacht in Indonesia and $US193,500 worth of Liber Pater wine for one unannounced recipient.

The list of nominees is filled with the kind of big name – Leonardo DiCaprio for Killers of the Flower Moon, Meryl Streep for Only Murders in the Building, Timothée Chalamet for Wonka – who were unable to promote their movies and TV shows for months during last year’s strikes by writers and actors.

In an attempt to juice viewership, more stars than usual have been invited to this year’s ceremony, where they can eat miso black cod from Nobu alongside the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Jon Batiste in the Beverly Hilton’s International Ballroom.

This year’s telecast (also on CBS’s sibling streaming platform Paramount+) could benefit from a plum timeslot – right after back-to-back NFL games – as well as pent-up demand for star-watching following the strikes and a crop of popular movies such as Barbie and Oppenheimer.

To punch up the energy during the ceremony, producers made the stage into a catwalk that juts into the ballroom, putting winners closer to the crowd. By keeping the tables stocked with Moët & Chandon, they’re banking on more of the friskiness the Globes have been famous for.

“I’m really hoping to showcase to people at home this feeling where you’re sucked into the show,” said Glenn Weiss, one of the producers overseeing the telecast.

The industry has a lot to gain from a stronger, more credible Golden Globes. Hollywood still loves award shows because the talent – the actors and filmmakers – loves them.

“It was a little messy getting here, but they did it, they professionalised up and down,” said Kelly Bush Novak, chief executive and founder of Hollywood public-relations firm ID, which was among 100 publicity companies demanding an overhaul of the Globes two years ago. “We wanted a Golden Globe to be an award our clients could once again be proud to receive.”

Whether the audience will still care remains an open question. Viewership for awards shows has been in decline across the board for years in a media landscape where prestige films are at risk of becoming another niche, alongside cup-stacking videos and video game livestreams.

After Oscars viewership dropped below 20 million for the first time in 2021, the show attempted to lure back viewers in 2022 with several controversial moves including cutting eight technical awards from the telecast and presenting a clip reel of fan-voted blockbuster movie scenes.

Their efforts were only modestly successful, bringing in about 16.6 million viewers – an improvement from the prior year but still the second-smallest audience in Oscars history.

Streaming services have their own reasons to try to salvage awards shows as an institution. Netflix, Hulu and other streamers compete with traditional studios for talent and have invested heavily in awards campaigns, signalling to stars that they’re supportive partners.

Netflix struck a multi-year deal last year to carry the Screen Actors Guild Awards, and Amazon Prime Video will be home to the Academy of Country Music Awards until 2025 at least.

Media and entertainment companies have shelled out more than $US300m in previous years for billboards during awards season, according to advertising data from investment bank Solomon Partners.

The Globes’ new ownership structure could lead to conflicts of interest, since Jay Penske owns three of the most influential Hollywood trade publications: Variety, Deadline and the Hollywood Reporter. He now also controls a major driver of those outlets’ advertising revenue and a central topic of their coverage.

A spokeswoman for the Globes declined to comment on potential conflicts of interest. Representatives for Penske Media, which owns the three publications, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The changes could present other unfamiliar challenges. When the HFPA ran things with its limited membership, stars and their handlers generally had a strong sense of which way voters were leaning. The HFPA’s demands for access to press conferences and personal time with stars were at the crux of the scandal, but it also made it easier for studios to assess and sway voters’ opinions on nominees.

This year’s expanded roster of nominees strikes some in Hollywood as a transparent bid for more media attention. More stars up for awards means more opportunities for their self-promotion.

To prove the Globes’ worth, the producers need to deliver a bigger audience than last year’s paltry viewership. “I would say it boils down to one number: 6.3 million,” said Stephen Galloway, a former executive editor of the Hollywood Reporter who is now dean of the film program at Chapman University.

“Do better than that, you’re back. You do worse, bye guys.”

EIGHT DECADES OF GOLDEN GLOBES

1943: The Hollywood Foreign Correspondents Association, the precursor to the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, is formed.

1944: The first Golden Globes ceremony, honouring only film achievements, is held at the Twentieth Century Fox studio in Los Angeles.

1998 and 2001: First Christine Lahti, then Renée Zellweger, nearly miss their big moments when their names are called for best actress … while they’re in the bathroom.

2008: The ceremony is cancelled due to the Writers Guild strike.

2013: During an acceptance speech, Jodie Foster addresses her sexuality in public for the first time, effectively confirming speculation that she is gay.

2018: Celebrities wear all black to the red carpet in support of the Time’s Up and #MeToo movement, a protest against sexual harassment in Hollywood.

2021: A Los Angeles Times investigation reveals the HFPA has no Black members, and that studios wooed voters with expensive gifts.

2022: Stars boycott the Globes in protest. NBC cancels the show, and winners are announced via Twitter posts.

2023: The HFPA disbands, selling all its rights and assets to Dick Clark Productions and Eldridge Industries. The Golden Globes becomes a for-profit company.

2024: The first Golden Globes ceremony post-HFPA is to be held.

Ellen Gamerman and Sarah Krouse contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout