Calls grow to include Israel’s ultra-Orthodox Jews in draft

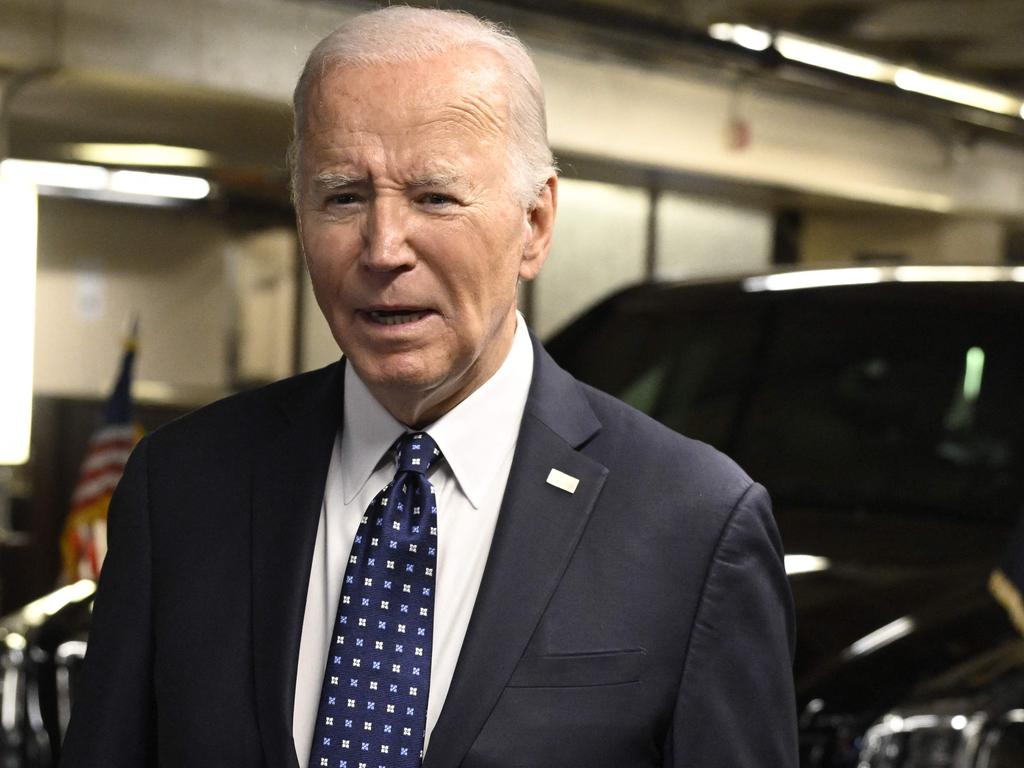

The defence ministry wants troops and reservists to serve longer, sparking demands to end a longstanding exemption for a slice of Israeli society.

For almost as long as the state of Israel has existed, the draft that powers the tiny country’s outperforming military has exempted its ultra-Orthodox Jews. The conflict in Gaza has reignited resentment about that pact and sparked new calls to up-end it, as the defence ministry pushes for regular soldiers and reservists to serve longer and keep Israel’s ranks stocked.

Some members of the governing coalition, the opposition and protesters are calling for an extension to mandatory service for the existing group of soldiers to be coupled with a new law that would draw recruits from the ultra-Orthodox community.

The demands to include the ultra-Orthodox community in the mandatory draft threaten the stability of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s governing coalition, which depends on ultra-Orthodox parties that have in the past threatened to abandon any government that extended the draft to their community.

Now the war against Hamas, nearing five months old, is proving so costly in terms of lives and personnel that even some in Netanyahu’s right-wing party are questioning whether Israel can sustain the longstanding policy. Israel is also facing the prospect of another and much more challenging war with Hezbollah, the Lebanese militant group.

Both sides have traded fire across the winding Israel-Lebanon border almost daily since the beginning of the war in Gaza.

The Defence Ministry proposal would extend mandatory military service to 36 months from 32, increase annual reserve-duty commitments and raise the age of obligatory reserve duty by up to five years, in some cases to age 52. It makes no mention of widening conscription to the ultra-Orthodox.

“The State of Israel’s current security needs require expanding the circle of those who carry the burden,” two lawmakers and a minister in Netanyahu’s Likud party wrote in a recent letter to the prime minister.

Never enshrined in law, the current exemption for ultra-Orthodox young men is set to expire at the end of March. The deadline, likely to be extended, is rekindling sharp tensions in Israeli society that were set aside as the country presented a largely united front against Hamas’s deadly Oct. 7 attacks.

“We sacrificed our lives for this country in the past months, you chose not to,” Amiel Yarchi, a right-wing Israeli journalist, wrote after returning from four months of reserve duty in Gaza, in a Facebook post addressed to ultra-Orthodox Jews.

It comes as the Israeli military is stretched thin between the war in Gaza, unrest in the West Bank and tensions on the northern border with militants in Lebanon.

“We’re in an emergency period and if we don’t extend the service time it will cut the number of troops in half and we cannot afford to do that right now,” said an Israeli official.

The draft exemption for ultra-Orthodox Jews – known as Haredim in Israel – dates back to soon after Israel’s foundation in 1948, when the government agreed to excuse them from military service so they could preserve a way of life nearly extinguished during the Holocaust.

Many Haredi men don’t serve in the military or work regularly. They instead choose to study holy texts in religious seminaries called yeshivas. They argue that they contribute to the state by preserving Jewish tradition and eliciting divine protection for Israel.

“It’s through the merit of yeshiva students studying that the soldiers are winning,” said Avraham Eli-Melech, 60, who works as a handyman in a yeshiva in the predominantly Haredi city of Bnei Brak.

The issue has dogged successive Israeli governments. Any attempt to enshrine the exemption through legislation has been either struck down by Israel’s Supreme Court on the grounds that it creates an unequal burden on citizens, or the terms of potential compromise legislation have brought down different governments that rely on ultra-Orthodox support.

At the time of the initial exemption, Haredim represented a fraction of the overall population. Now, more than seven decades after Israel’s founding, the community makes up 13 per cent of the population, and Haredi men represent 17 per cent of draft-age males.

In an indication that pre-Oct. 7 tensions are now beginning to re-emerge, signs were hung Saturday night on highway passes across Israel that said, “We are all brothers. We all enlist.” Several thousand demonstrators also rallied that night in central Tel Aviv, calling for elections.

Some reservists, exhausted after months of fighting in Gaza, say they are ready to push for a more equal distribution of the security burden across Israeli society.

“The social contract needs to be rewritten,” said Uri Keidar, who served as a reservist for four months in Gaza and heads an Israeli civil-society organisation that seeks to reduce religious sway over the state. “We can’t go back to October 6 as if nothing has happened.”

Similar sentiments are showing up within Netanyahu’s coalition. “It is no longer possible to accept with equanimity a situation in which certain groups in society shoulder the burden of security, with the high price that it exacts, while other groups of the Jewish people continue with their normal lives,” the Likud members wrote in the letter to Netanyahu.

That points to a shift in the debate over the exemption, according to Israeli political analysts.

“The general, non-Orthodox public has lost its appetite for this unjust and unequal arrangement,” said Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem-based think tank. The enlistment debate might “force Netanyahu to choose between his loyal political allies and big parts of his own constituency,” he said.

After Likud, two ultra-Orthodox political parties make up the largest bloc in the current government, with 18 seats in the 120-seat Knesset. They are key to Netanyahu’s grip on power, since his original allies in the wartime government control just 64 seats in total. Rival Benny Gantz brought his National Unity party into the government at the outset of the current war to bolster national unity.

Earlier this week, Opposition Leader Yair Lapid sent a letter to Defence Minister Yoav Gallant in which he warned that “we will not be able to continue filling the streets with slogans of ‘together we will win,’ if we don’t enlist together.”

A senior official in United Torah Judaism, one of two Haredi political parties that are part of Netanyahu’s coalition government, said the enlistment issue is “very sensitive” and that the party has decided to “not get involved” in the current debate over bills.

The Haredi political leadership knows that after the Hamas attacks on Oct. 7, the status quo cannot stand, said Israel Cohen, a political commentator for a Haredi radio station.

But Haredi religious leaders haven’t publicly grappled with the renewed public demand to end their community’s exemption from military service. If a leading rabbi were to oppose any change, Cohen said, it could pull the entire community in that direction.

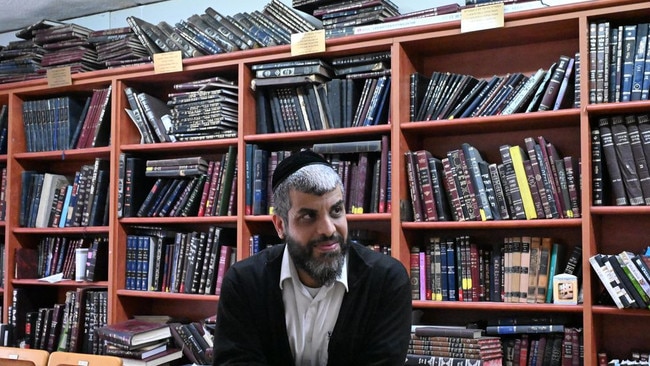

Yosef Gamliel, 43, a rabbi in Bnei Brak, said the only thing that could push Haredim to join the military as a bloc is if the spiritual leadership changed their stance.

“We have survived for thousands of years by keeping our tradition,” he said.

The Wall Street Journal