Beijing weighs how far to go in backing Putin on Ukraine

With the threat of a Russian invasion of Ukraine looming, China’s final arbiter of power — the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee led by President Xi Jinping — has largely disappeared from public view.

Behind closed doors, according to people with knowledge of the matter, one topic of intense discussion is how to respond to the Russian-Ukraine crisis and back Moscow without hurting China’s own interests.

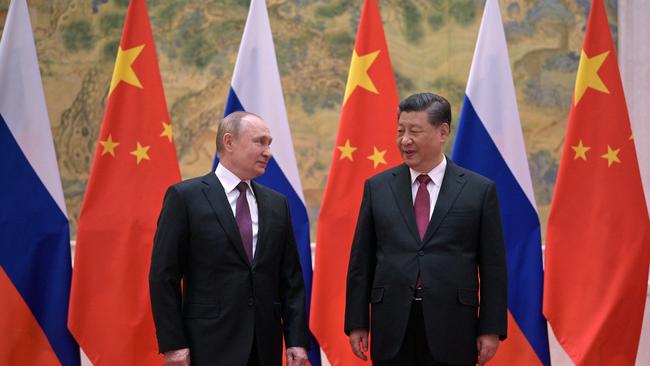

The brooding has gone on for more than a week, practically since Mr. Putin got on a plane back to Moscow after meeting with Mr. Xi and attending the Feb. 4 opening of the Beijing Winter Olympics. The unusually extended discussion underlines how urgent and delicate the situation is for Beijing despite Mr. Xi’s public stance of support for Russia.

Mr. Xi’s endorsement of Russia’s opposition to any expansion by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization — a central demand from Moscow in its standoff with the U.S.-led allies over Ukraine — marked China’s most explicit support to date of the Kremlin in a confrontation.

Beijing has been careful not to green light Russia’s possible invasion of Ukraine. But the joint statement by Messrs. Xi and Putin on Feb. 4 nonetheless represented Beijing’s closest alignment with Moscow since the early years of the Communist bloc’s Cold War with the West. That has stirred up some unease in China’s official circles, according to people close to the government, because it signalled such a fundamental shift in China’s foreign policy.

“It’s one thing for China to back Russia in opposing NATO enlargement, as it costs nothing,” said Sergey Radchenko, a professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University in Bologna. “It’s quite another for China to help Russia evade the economic sanctions it would face if it invades Ukraine.”

With top leaders hunkering down in the Zhongnanhai leadership compound as the Beijing Winter Olympics is in full swing, the debate has centred both around principles as well as the practical reality Beijing faces, the people familiar with the issues said.

Whatever the top seven leaders decide will depend on how the crisis evolves, the people said, and their discussion will then be presented to the 25-member Politburo, which will convene later this month.

China’s longstanding foreign-policy stance, set forth soon after the founding of Communist China by then-Premier Zhou Enlai in the “five principles of peaceful coexistence,” is to not endorse any country’s aggression or intervention in another’s affairs.

That helps explain why China hasn’t recognised Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, or fully supported Moscow when it deployed forces to Kazakhstan early this year to quell unrest in the Central Asian nation.

Beijing is aware that by so closely aligning China with Russia on European security issues, it risks further alienating Europe and pushing countries on the continent further into the orbit of the U.S.

On Wednesday, Mr. Xi made his first remarks on Ukraine that China has made public since Mr. Putin left. In a phone conversation with French President Emmanuel Macron, the Chinese leader called for the use of dialogue such as the Normandy talks — a diplomatic channel established in 2014 to end the fighting in Ukraine whose members are Germany, Russia, Ukraine and France — to reach “a comprehensive settlement of the Ukrainian issue,” state media reported.

On a more practical level, Beijing feels the need to protect its own economic and security interests in regions that could be under threat from the Kremlin. Notably, Ukraine is a member of Mr. Xi’s signature Belt and Road initiative, the vast infrastructure lending and construction program designed to put China at the heart of trade from Southeast Asia to Europe.

State-owned Chinese engineering, power and construction companies in recent years have invested billions of dollars in projects in the Eastern European country, a big supplier of cooking oil, machinery and nuclear reactors to China. In late 2020, Beijing and Kiev agreed to deepen their Belt and Road co-operation, with Vice Premier Liu He, Mr. Xi’s longtime economic tsar, pledging to promote “sound and stable bilateral relations” with Ukraine.

Meanwhile, China has been building a vast network of pipelines in Central Asia to secure its supplies of oil and gas, and diversify the source of its suppliers. Many countries that those pipes go through are former members of the Soviet Union.

“Putin is a major headache for Beijing,” said Carl Minzner, senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “A precedent for Russian intervention in former Soviet lands would increase risks to China’s Central Asia energy pipelines.”

In addition, giving Russia a free hand to intervene in the post-Soviet space would potentially hurt China’s longer-term efforts to displace Russia as the main power in Central Asia.

Reflecting Beijing’s unease on Russia’s position on Ukraine, Mr. Minzner noted, China’s state-media coverage of the Ukraine crisis has settled into a pattern: It blames the U.S. and its allies for delivering weapons to Ukraine and hyping the threats from Russia, but repeats the official Ukrainian position on the need for negotiations.

Meanwhile, after Washington over the weekend warned of an imminent Russian invasion and pulled American diplomats from Kiev, China’s foreign ministry spokesman said the Chinese Embassy in Ukraine was operating as usual. The Foreign Ministry didn’t respond to questions for this article.

So far, the most tangible help Beijing has given Moscow involves its agreements to purchase oil and gas from Russia — in deals that Moscow said are valued at an estimated $117.5 billion and would stretch more than two decades. Terms of the deals aren’t disclosed.

Within China, some officials have raised questions about whether it makes sense to get locked in such long-term contracts when energy prices are high. Beijing could try to negotiate terms more in China’s favour, said an economic adviser to the governm

ent.

In addition, China’s leaders are also weighing the risk of financial and trade restrictions from Washington should Beijing do substantially more to help Russia evade American sanctions in the event of an invasion, according to the people with knowledge of the discussion.

Chinese banks, for instance, still count on global financial networks to process cross-border trade and other transactions. Chinese manufacturers of smartphones and electric vehicles also rely on American chips and other high-tech products. Existing U.S. export-control measures have already hurt big Chinese firms like Huawei Technologies Co.

Relations between Beijing and Moscow have traditionally been fraught. The former Soviet Union inspired the Communist revolution in China, and dispatched tens of thousands industrial and other specialists to the country to help Mao Zedong build the new China. The ties became so tight that the Soviets were called “lao dage,” or elder brother, by many Chinese.

By the late 1950s, however, the relationship broke down over ideological and other tensions. China moved closer to the U.S. in the following decades, lending Washington a hand in winning the Cold War over Moscow and helping China’s own opening to the world.

Since Mr. Xi came to power almost a decade ago, China and Russia have gotten closer as each country’s relations with the U.S. soured. Russia is helping China develop an early-warning system for nuclear weapons, while China has been buying up Russian energy.

Mr. Xi, whose first foreign trip after becoming China’s leader was to Russia, in 2013, has said he had been inspired by Russian literature — such as Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s novel “What Is to Be Done?”—in which the leading character would sleep on a bed of nails to strengthen his revolutionary will.

He and Mr. Putin, seen by many Chinese as a model of masculinity, have met 38 times.

After the united-front display at the Xi-Putin summit on Feb. 4, there were few images of Messrs. Xi and Putin together. At a state-banquet lunch the day after the Olympic opening at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, Mr. Putin wasn’t present. A People’s Daily photo of the lunch showed an enormous table, with guests seated far apart and a giant winter-sport scene centrepiece preventing any intimate conversation. State media identified the attendees only as unnamed “foreign dignitaries.” The guest of honour had already left.

“Both China and Russia don’t want to feel they’re obligated to completely sacrifice their own interests when the other country does something destabilising,” said Joseph Torigian, an expert on authoritarianism at American University in Washington.

China’s top leaders have spent days weighing how far Beijing should go to back Russian President Vladimir Putin and how to manage a partnership many call a marriage of convenience as opposed to one of conviction.