AUKUS is the Indo-Pacific pact of the future

The impetus for the agreement, Prime Minister Morrison told me in an interview during his recent trip to Washington, came from the Australians. After years of escalating pressure, last November Chinese diplomats in Canberra warned that to enjoy better relations with Beijing, Australia’s government must address 14 Chinese grievances. It must, among other things, stop funding “anti-China” research, refrain from provocative actions like requesting a more thorough World Health Organisation investigation of the origins of Covid-19, stop opposing strategic Chinese investments into Australia, and block private media outlets from publishing “unfriendly” news stories about China.

Meanwhile, the size and speed of China’s naval build-up had forced Australian defence planners to rethink their national defence strategy. One casualty of that review was confidence in Australia’s strategic partnership with France which was anchored by the now-cancelled submarine program. Faced with a relentless and rising China, the Australians concluded that only closer ties to the U.S. could provide the deterrence and protection they need.

As the Morrison government cast about for ways to stave off Beijing, it hit on a novel approach. There is little appetite in the Indo-Pacific for a formal regional security pact like NATO, but Australia wanted something more solid and durable than the kind of loose ad hoc coalition of the willing that American diplomat Richard Haass famously calls a “posse.” Instead, the Australians would persuade the British and U.S. partners to use the deep trust that the members of the “Five Eyes” intelligence partnership (America, Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) have built up over the decades since World War II to create something new.

Between the intelligence sharing over terrorism following 9/11 and more recent co-operation over China, the Five Eyes had never been more robust. Why not, the Australians thought, expand the partnership from intelligence to include research and defence planning? A model for this co-operation already existed: The U.S. shared highly sensitive nuclear propulsion technology with the British submarine program. The Australians thought joining that program and proposing further tripartite collaboration in fields ranging from quantum computing to artificial intelligence, electronic warfare, missiles and cyber could offer economic as well as military and diplomatic benefits.

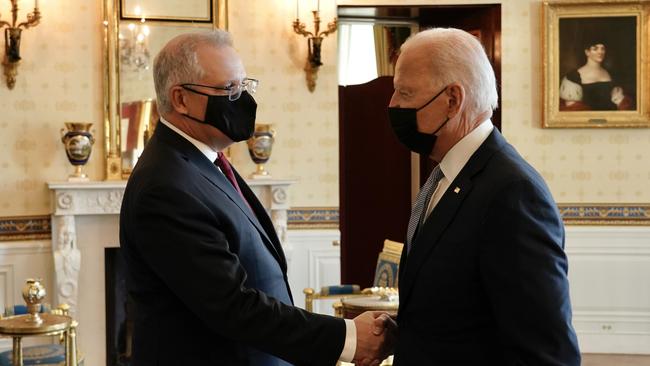

With strong support from the Biden administration, especially from Jake Sullivan and Kurt Campbell at the National Security Council, and the enthusiastic embrace of a U.K. prime minister eager to put substance behind his “Global Britain” slogan, the agreement came together, by the standards of international diplomacy, at blistering speed.

What comes next will be more difficult as the three countries struggle to bring their unwieldy national-security bureaucracies into alignment and get the private sector to buy in to the process. Describing the level of co-operation he’d like to see, Mr. Morrison is ambitious. When it comes to defence and security planning, he says, “we want to be in on it before it’s even thought of … We want to be in the thinking of the group about what the [defence and technological] needs are.” That won’t happen overnight, if it happens at all, but whatever form it ultimately assumes, Aukus has a unique flexibility and depth. And in an age when the link between information technology and defence capability has become critical, the centrality of cooperative research and development massively enhances the value of this new kind of alliance.

These are all reasons Aukus is a better model for pacts with Indo-Pacific powers than the alliances that fought the Cold War. Indo-Pacific countries are less interested in pooling sovereignty and creating rule-driven, bureaucratic structures than many European states are. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations is looser than the European Union, and the Quad is looser than NATO. If Chinese behaviour continues to drive its neighbours into closer partnerships with the U.S. and each other, Japan and Taiwan may enter deeper and more Aukus-like arrangements — and perhaps into Aukus itself. A bloc that shares technology and coordinates defence policies that includes Japan, India, Taiwan and the Aukus countries would be a formidable force.

The Wall St Journal

International summits almost inevitably end in grandiose joint communiques, most of which are quickly forgotten. This month’s announcement of the Aukus partnership by President Biden, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison won’t be. This isn’t because the pact made France unhappy or even because it highlights America’s long-term commitment to the Indo-Pacific. Aukus is a deep but flexible partnership between leading tech powers that could shape the 21st century and serve as the model for U.S. alliances in the Indo-Pacific.