America’s vaccine rolls out but it will take months to reach everyone

Pfizer is packing boxes with thousands of its COVID-19 vaccines for shipment around the US, as hospitals gear up for mass jab effort while confronting viral surge.

Pfizer Inc. is packing boxes with thousands of its COVID-19 vaccines for shipment around the US, as hospitals gear up to give shots while also confronting the surging pandemic.

Trucks carrying the fragile cargo at minus-94 degrees Fahrenheit will start rolling out of Pfizer plants in Michigan and Wisconsin on Sunday. Doses are scheduled to start arriving at hospitals on Monday.

Health-care workers treating COVID-19 patients, nursing-home residents and perhaps others could start getting inoculated soon thereafter, though it might take a day or two for facilities to train staff and begin injections.

The rest of the population will have to wait, as the drugmakers produce and ship more of the doses.

After the fastest development of a vaccine ever recorded, distribution of the shots kicks off an equally formidable challenge: a monthslong inoculation campaign not seen since efforts to eradicate the polio virus.

“People should not forget how extraordinary it is that we are even talking about having a vaccine by mid-December at all. In January, I don’t think anybody thought this was feasible,” said Kelly Moore, associate director of immunization education at the Immunization Action Coalition.

Initial supplies will be limited. Pfizer projects it will deliver 25 million doses to the U.S. this year, including 2.9 million doses the first week.

The US now begins its largest vaccination campaign ever, bringing together governments, small and big hospitals and retail pharmacy chains with the goal of vaccinating hundreds of millions of people against the coronavirus swiftly.

The daunting task will include distributing a vaccine that must be stored at extremely cold temperatures, and since inoculation requires two doses three weeks apart, the challenge of ensuring people return for a booster shot.

It also means convincing the large numbers of Americans hesitant to get vaccinated that the shot is safe to take.

A COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer Inc and partner BioNTech SE is the first to gain the US government’s permission to go into use in the country, a landmark step in efforts to beat back the raging pandemic.

The US Food and Drug Administration’s authorisation of the shot on Friday US time, following ts record-setting swift development, sets the stage for administration of inoculations to begin within a day or two.

The decision clears use of the shots in people 16 years and older, including the elderly.

President Donald Trump, in a video posted on Twitter Friday night, called the vaccine a “medical miracle”,

“This is one of the greatest scientific accomplishments in history,” he said, speaking from the Oval Office. “It will save millions of lives and soon end the pandemic once and for all.”

The President said the vaccine was safe and would be free for all Americans.

The FDA’s first green light for a COVID-19 vaccine comes little more than a week after a similar authorisation in the UK. It follows a 44,000-person study, which found that the shot was 95 per cent effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 and was generally safe.

Initial supplies will be limited. Pfizer plans to distribute about 25 million doses in the US by the end of the year, potentially enough for 12.5 million people because the vaccine requires two doses.

The people first in line will have to wait at least until Monday to get vaccinated, because the shots must be shipped to hospitals and other sites.

Most Americans wouldn’t be able to get vaccinated before the northern spring or summer, because Pfizer needs time to make enough doses.

If enough people eventually take the shots, schools, businesses and restaurants could start fully reopening. A vaccine’s impact comes not only if it is effective in an individual but also if it is widely taken.

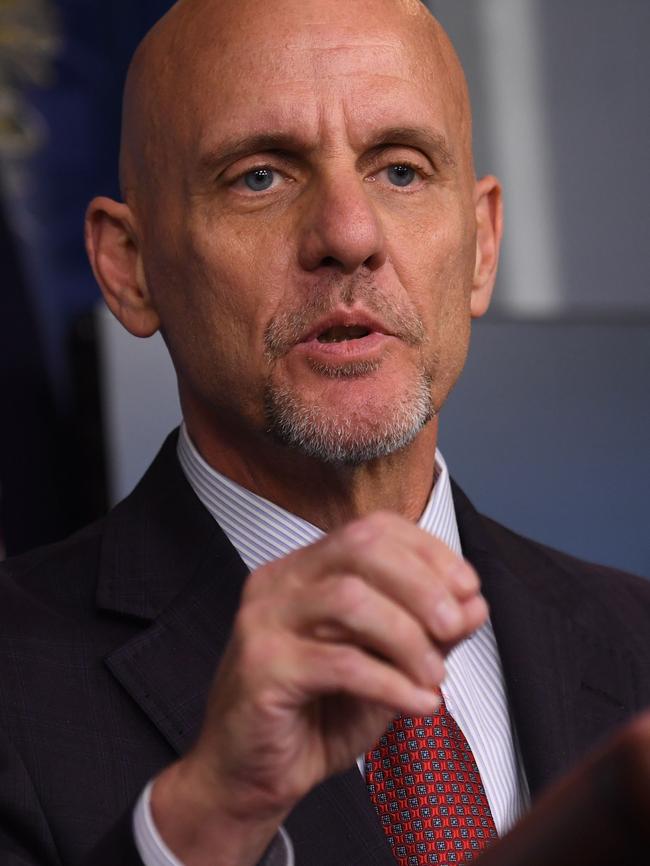

“The FDA’s authorisation for emergency use of the first COVID-19 vaccine is a significant milestone in battling this devastating pandemic that has affected so many families in the United States and around the world,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said.

In announcing the authorisation, the FDA cautioned that the vaccine might not protect everyone who gets it.

The agency also said doctors and nurses administering the shot should keep on hand treatments for managing immediate allergic reactions. And the FDA’s materials for doctors and nurses said the vaccine should not be administered to people with known histories of a severe allergic reaction to any components of the vaccine.

UK health authorities recently warned against giving the vaccine to people with a history of serious allergic reactions, after two health-service workers suffered the reactions after getting vaccinated. Researchers excluded people with severe allergic reactions to vaccines from the late-stage study of the Pfizer-BioNTech shot.

The FDA also said the vaccine might not be as strong in people with compromised immune systems, including those taking drugs that weaken the immune system.

Since COVID-19 swamped hospitals and sank the economy, health authorities, government officials and business leaders have awaited the arrival of vaccines and their potential to stamp out the virus.

Vaccines typically take years to create, test and bring to market. Pfizer and BioNTech were among dozens of drugmakers that raced into action.

“We have worked tirelessly to make the impossible possible, steadfast in our belief that science will win,” Pfizer chief executive Albert Bourla said.

Not far behind are Moderna Inc, which has a shot on track for FDA authorisation in as little as a week, and several other drugmakers with candidates in the later stages of development.

Shots developed in China and Russia have already gone into use in those countries and in others.

The development and authorisation of Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine advanced faster than any shot has ever progressed in the West, in less than a year. A mumps vaccine previously had been the fastest to market, taking about four years.

“It’s unbelievable how swiftly the authorisation went,” BioNTech chief executive Ugur Sahin said.

Pfizer and BioNTech moved quickly by turning to a promising but unproved gene-based technology, known as messenger RNA (mRNA) after the molecules that carry to cells DNA’s instructions for making proteins.

Moderna’s vaccine also employs mRNA technology.

Using the genetic sequence of the coronavirus, BioNTech researchers synthesised mRNA that would teach cells to make a version of the spike protein protruding from the coronavirus. Production of the protein would prompt an immune system to develop defences that mobilise against the real virus.

Given the urgent need for a vaccine, the FDA made its decision within weeks, a fraction of the months it normally takes to consider an application. Technically, the agency granted a temporary clearance, known as an authorisation for emergency use.

The FDA said it still held the vaccine to the high standards it would have demanded if there wasn’t a pandemic.

The agency has issued emergency-use authorisations, which are different than a normal approval, during recent months for several drugs, though not a vaccine until now.

Peter Marks, director of the FDA division that reviews vaccines, said “efforts to speed vaccine development have not sacrificed scientific standards or the integrity of our vaccine evaluation process”.

The US government placed an initial order for 100 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for nearly $US2 billion ($2.65bn), with the option to purchase 500 million additional doses.

Pfizer has been producing shots at plants in Belgium and Michigan. To prepare for distributing the doses, the company shipped about 750,000 vaccines from its Belgium plant to the U.S.

The federal government decides how much of the vaccine supplies that US states will get, based on the size of their populations. States and other jurisdictions will initially get 2.9 million doses from Pfizer, with an additional 2.9 million following three weeks later for the second dose. Weekly shipments of doses would follow.

States, as well as some territories, federal health agencies and large cities, will determine where the millions of shots will be delivered, and who should get vaccinated first.

Hospitals, health clinics and certain public-health locations will serve as most vaccination sites initially. Pharmacies will be able to give inoculations as more doses are made and more people are able to get access.

“As Americans get vaccinated, we need to continue taking steps like washing our hands, social distancing, and wearing face coverings to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our communities,” US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention recommended the nation’s 21 million health-care workers and three million nursing-home and other long-term care residents be the first to receive any COVID-19 vaccine doses. States don’t have to follow the CDC’s guidelines.

CVS Health Corp and Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc pharmacies will deliver and administer most vaccine doses for the nation’s approximately 15,600 nursing homes and 29,000 assisted-living communities, once states give the go-ahead.

McKesson Corp, which will be distributing vaccines other than Pfizer’s, has been shipping to hospitals and other administration sites kits with syringes, alcohol prep pads and other medical supplies needed to administer Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine.

Health authorities do not expect there will be enough supply to vaccinate the broader, general population until the northern spring or summer next year. By then, vaccines from AstraZeneca PLC, Johnson & Johnson and other companies might be cleared and able to augment supplies.

How soon vaccinations with the initial supplies will start is unclear. Once a vaccine gets to a hospital, it could start administering shots within hours, vaccine experts say, though it could also take days as hospital workers learn how to handle the containers storing the shots at ultracold temperatures.

A big challenge is persuading millions of people to get vaccinated. Surveys have found large percentages of people in the US, many of whom are in high-risk categories, are hesitant to get vaccinated, partly out of concern development of the shots was rushed.

Fuelling some of the hesitancy has been the Trump administration’s own actions and comments, according to the surveys.

During the presidential campaign, Mr Trump urged the FDA to authorise a vaccine by election day. He also said, during the first presidential debate and in a news conference in September, a vaccine would be available within weeks.

FDA and industry officials made statements seeking to ease any concerns that political pressure was forcing them to rush out shots.

The FDA also published detailed guidelines outlining the agency’s requirements for authorising a vaccine.

It waited for a panel of outside experts to meet, on Thursday, to review the performance of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in testing. The committee voted 17 to 4 to recommend authorisation.

Earlier on Friday, White House chief of staff Mark Meadows told Dr Hahn, the FDA commissioner, that he should look for a new job if the FDA did not authorise the vaccine on Friday, according to a senior administration official, prompting the agency to speed up its plans.

Dr Hahn, in a statement, had denied his job was threatened by the call, which was first reported by The Washington Post.

[AFP reported Dr Hahn told reporters: “The representations in the press that I was threatened to be fired if we didn’t get it done by a certain date is inaccurate.” He added that the decision, which had been expected a few days later, was “based on the strongest scientific integrity”.]

with Bojan Pancevski, Peter Loftus and Andrew Restuccia.

The Wall Street Journal

America’s Distribution Plan

US public-health authorities have started setting priorities for who should get the COVID-19 vaccine first. Based on targets for distribution, here’s a potential scenario for how doses could be distributed for Pfizer’s vaccine and for Moderna’s, which is next up for approval.

DECEMBER DISTRIBUTION TARGET 20 MILLION PEOPLE

First to get the vaccine will be from:

Health-care personnel 21 million

Long-term care-facility residents 3 million

**

JANUARY DISTRIBUTION TARGET 30 MILLION PEOPLE

Second-highest priority among:

Essential workers (non-health-care) 87 million

**

FEBRUARY – MARCH DISTRIBUTION TARGET AT LEAST 50 MILLION PEOPLE

**

BEYOND MARCH

Third-highest priority:

100 million adults with high-risk medical conditions

53 million adults aged 65+ years

Note: These roll-out estimates are based on the timing of first dose. Each person is given two doses, three to four weeks apart. Numbers for demographic groups are based on US populations of each group. Because of overlap between groups, the number of adults over 65 and those with high-risk conditions in line for vaccinations is smaller than their combined populations, and some would be vaccinated earlier.

Sources: Department of Health and Human Services (vaccination goals); CDC (prioritised groups). Erik Brynildsen, Todd Lindeman, Josh Ulick and Taylor Umlauf The Wall Street Journal

HOW MESSENGER RNA VACCINES WORK

The vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech uses a new gene-based technology known as mRNA.

Traditional Vaccines:

1. In classic vaccines, such as those against measles and polio, the patient is inoculated with weakened or inactivated versions of the virus. This triggers the immune system to produce specialised antibodies that are adapted to recognise the virus.

2. After vaccination, the antibodies remain in the body. If the patient later becomes infected with the actual virus, the antibodies can identify and help neutralise it.

Vaccines now in the works:

Scientists have identified the genetic code that coronavirus uses to produce spike proteins. They employ molecules called RNA to ferry this genetic information into our cells. The RNA is protected by a lipid coating.

Instead of using the whole virus to generate an immune response, these vaccines rely on coronavirus’s outer spike proteins, which are what antibodies use to recognise the virus.

When injected into a patient, the RNA enters healthy cells where it helps orchestrate the production of coronavirus spike proteins.

Once exported from the cells, the spike proteins prompt the immune system to mount a defence, just as with traditional vaccines.

Source: Nature Magazine

Alberto Cervantes, Josh Ulick /The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout