America voted for a rest, not a revolution

The Biden administration’s progressive lurch in its first 100 days has been met with underwhelming approval ratings.

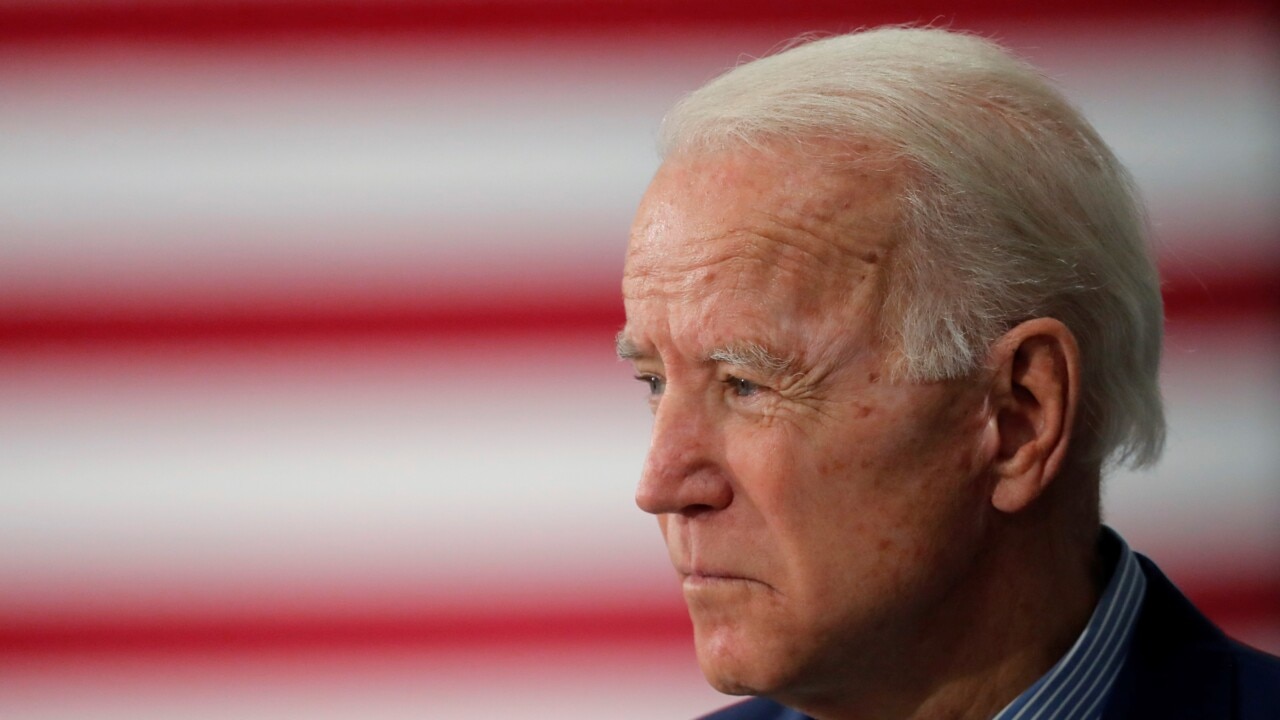

Joe Biden aspires to be the second coming of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, so short of his showing up to work in a wheelchair and sucking on a cigarette holder, the first hundred days, which he marks this week, will serve as the most symbolic reminder of the president’s sense of historic purpose.

The ritual observation of the passage of FDR’s calendrical contrivance promises to be even more turgid than usual this year. President Biden’s first address to a joint session of Congress, which he delivers on Wednesday, will come with special solemnity. We will be reminded that delivering the nation from the baleful legacy of a one-term Republican in the midst of a national crisis with an urgent flurry of executive and legislative initiatives is what Democrats do.

We can leave to future historians whether the creation of the White House Gender Policy Council will prove as consequential as that of the Tennessee Valley Authority. To be fair, different times pose different challenges. Eleanor at least would surely approve. Perhaps she’s having fireside chats with Dr. Jill the way she used to with Hillary Clinton.

FDR had a famously complaisant press covering him, but even he might have blanched at the deference shown by Mr. Biden’s media guardians. Newspapers did eventually rouse themselves to object that the 1937 effort to pack the Supreme Court might be constitutionally problematic.

Today’s friendly stenographers don’t see the problem at all, and faithfully convey the White House line that the same idea is a much-needed “reform.”

Given the revisionist climate we live in, though, Mr. Biden might not want to overdo the historical parallels with a white, male Democrat of the 1930s. We can only speculate on how FDR might have fared in an unconscious-bias training session led by a modern diversity, equity and inclusion officer, but back in the 1930s the Jim Crow rules enforced by his fellow Democrats meant billy clubs, beatings and lynchings, not a slight reduction in the number of early-voting drop boxes.

Despite the strenuous efforts to give Mr. Biden an early plinth in the pantheon of great presidents, the American public seems unconvinced. Polling conducted to mark the 100-day point puts his popular approval somewhere in the low 50s on average. That is well below all his modern predecessors — except the immediate one.

This relative long-term underperformance but short-term overperformance might provide a clue to the larger political context of this burgeoning presidency.

The White House would like you to believe that the progressive lurch it has taken in the first 100 days — contrary to the promises Mr. Biden made during the campaign — is going down well with voters. Pointing to his 10-point improvement over President Trump, his aides say there’s popular support for the hefty expansion of government they have embarked on. But a more likely explanation is that for a critical mass of Americans in the shrinking center of politics, Mr. Biden’s singular appeal is that he is not Mr. Trump.

It’s hard to overstate the extent to which the Trump presidency was for nonpartisans simply wearying. It often felt like being a child of parents going through the collapse of a desperately unhappy marriage: Daddy rage-tweeting about some latest grievance while the media howl back in an angry storm of wild accusations and threats.

The Biden presidency by contrast is a throwback to an ideal of an earlier age of family tranquility: Old Joe sitting benignly in the La-Z-Boy, listening to Bing Crosby on the record player. Mother Media dutifully handing him his slippers and a scotch and reassuring him all is well. The kids quietly doing their homework, and everyone’s in bed by 9.

This contrast alone — the dialing down of the hysteria we’ve lived with for four years — probably explains the 10-point difference in the Trump and Biden ratings.

The cleverest White House move has been the careful rationing of the president’s presence in the lives of ordinary Americans, the rediscovery that scarcity has value.

What happens when this return to normality simply feels, well, normal again? The Biden people hope that an economy roaring back to life in the early stages of post-pandemic euphoria will maintain their political momentum and Americans will retroactively endorse the progressive course they’re on.

But there’s an alternative possibility: that the resumption of normal political service reminds at least half the country that an administration that has exceeded even the left of its own party’s expectations may not be what the country needs.

WSJ

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout