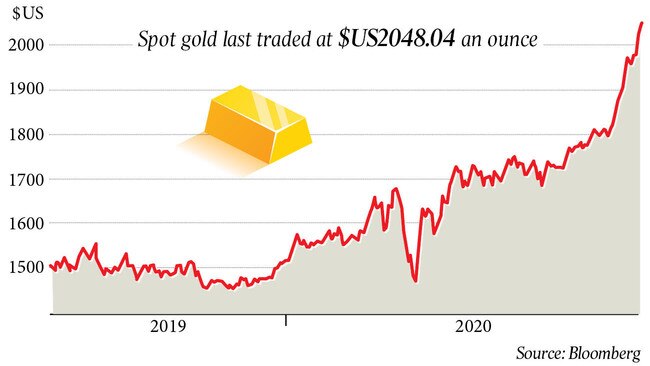

All-time high as investors take a shine to gold

There are good reasons investors are buying up gold ... and as a result, the ‘ultimate insurance policy’ is about to set records.

Gold prices are on track to notch new records this week, after closing at over $US2000 a troy ounce for the first time on Tuesday in New York trading.

That marks a fresh milestone in a bull run that began in late 2018 and has gathered momentum during the coronavirus pandemic.

The precious metal has soared almost 35 per cent in 2020, outstripping the rally in the Nasdaq Composite Index of high-flying technology stocks.

Here is how the gold market works, and why prices are rising.

-

What is the gold market?

There are two gold markets, closely linked because investment banks and other big players are active in both.

The first is the physical market, which brings together miners, refiners, jewellers, central banks, electronics manufacturers, banks and investors. London is the focal point, dating back to 1697. Shanghai, Zurich, Dubai and Hong Kong are also hubs.

The second market is the futures market, for swapping financial contracts based on gold. This market is electronic, hosted by New York’s Comex exchange, and sets the prices you read about in the media. It gives investors an opportunity to speculate on gold prices rising or falling without holding the metal, and miners a way to insulate themselves from unexpected price drops.

-

How does the physical market work?

Deals to buy, sell and lend gold in London are struck privately, rather than on an exchange. To reduce the amount of metal that has to be shunted from vault to vault, five banks act as a clearing house, balancing out each other’s sales and purchases. Some of them provide vaults, offering clients a safe place to stash gold.

The Bank of England guards more than 400,000 bars beneath the streets of the City of London, largely on behalf of the UK government and other central banks, a hoard second only to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Prices are quoted by troy ounce of pure gold, and bullion trades in batches of 400-ounce bars.

London prices are fixed in twice-daily auctions and act as a benchmark in physical markets. When a watchmaker buys gold from a refiner, it usually does so at a premium to the London price.

To avoid paying for tonnes of gold, tying up millions of dollars in cash, industrial users often borrow metal instead of buying it outright. Banks either lease it to them, charging interest, or lend with more complex forward, swap and repurchase deals.

-

How does the financial market work?

Futures are standardised contracts that lock in prices for gold that will change hands at a specified date. Buyers and sellers agree to swap 100 troy ounces (a new Comex contract that allows delivery of 400 ounces has barely traded). Gold futures trading data go back to the final day of 1974, when Comex launched the market to coincide with a law allowing Americans to own bullion for the first time in four decades.

Most traders exit futures trades before they actually exchange gold. Recently, however, more investors have taken delivery of gold on the Comex, a sign demand for physical gold is unusually high.

Gold’s bull run hit new heights on Wednesday, as analysts suggest the #coronavirus crisis could propel the precious metal above $US3000 an ounce in 2021, and junior explorers rush to cash in on gold’s bull run. @crankynick #gold #commodities #ausbiz https://t.co/sfwZCsId7y

— Business Review (@aus_business) August 5, 2020

-

Why are gold prices soaring?

The main reason is this year’s drop in yields on US Treasuries to levels below the expected pace of inflation. Unlike bonds or bank deposits, gold doesn’t pay any income. As a result, owning gold means missing out on yields from other assets when interest rates are high. When real yields are negative, gold’s lack of yield becomes a strength.

The Federal Reserve’s March decision to slash interest rates to just above zero and buy hundreds of billions of dollars of bonds has pulled down yields in fixed-income markets, prompting investors to buy gold instead. Some money managers expect inflation to pick up once the economic crunch is over, which would act as a further drag on real yields if nominal rates don’t rise.

Investors are also buying gold because they think it will hold its value if stocks take another tumble. Enthusiasts take this argument a step further, contending that gold is the ultimate insurance policy against a scenario in which the US government defaults or kindles inflation to alleviate the burden of debt.

“Gold is a haven,” said Rhona O’Connell, head of market analysis for Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia at StoneX. “It doesn’t have anyone else’s political or financial risk associated with it.” Another tailwind for gold right now is the depreciation in the US dollar. Buyers outside the US are willing to pay a higher dollar price when the greenback weakens, making gold cheaper in terms of their home currencies. This relationship doesn’t always hold: gold and the dollar shot up in tandem in March during a period of turmoil in financial markets.

-

How does this compare with previous bull runs?

Two other run-ups have taken place since President Nixon cut the link between gold and US dollars in August 1971. The most dramatic spanned the rest of the 1970s, when inflation exacerbated by twin oil crises led the gold price in London to soar from $43 a troy ounce to $850 in early 1980.

“We’re in World War Eight, if you believe the market,” a commodities broker named James Sinclair told the New York Times on January 21 of that year, the day prices crested.

*GOLD PRICES EXTEND RALLY TO HIT NEW ALL-TIME HIGH OF $2,070/OZ AS PRECIOUS METAL SURGE CONTINUES $GC_F $GLD pic.twitter.com/Kfgqy9BZws

— Investing.com (@Investingcom) August 6, 2020

Prices jumped again from 2008-11, when interest rates fell because of aggressive stimulus measures by the Fed and a recession that was, at that point, the worst since the Great Depression. Worries that bond-buying by the Fed would lead to runaway inflation — which didn’t transpire — also contributed to the advance.

-

Will gold prices keep rising?

It took three years after the start of the previous financial crisis for gold prices to peak, notes Edmund Moy, who was director of the US Mint at the time.

“They kept on going up until it was very clear that the US economy would recover slowly and that there would not be inflation,” he said. “I think we’re at the very beginning of momentum for gold prices going up.”

Gold prices tend to overshoot, according to Fergal O’Connor, an economist at University College Cork who has studied the market’s history. Still, he expects them to fall back to a higher level than they were before the pandemic because institutional investors are adding to their gold holdings, removing a chunk of available supply. The return of jewellery demand in China and India could also boost prices.

I have little Gold joke - it’s just precious.

— Fergal O'Connor (@a_fergal) July 25, 2020

The biggest deciding factor would be the direction of interest rates, adjusted for inflation, Standard Chartered Suki Cooper said. “It’s real yields that are really driving the flows into gold.”

-

Is gold a commodity or a currency?

Both. Gold is a commodity in that it derives its value, in part, from its use in products like jewellery. Banks that are active in the physical market trade gold on their commodities books, and the futures market in the US is regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Gold is treated like any other commodity on banks’ balance sheets under the Basel III regulatory guidelines, designed to avoid a repeat of the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Gold is also a currency. For millennia, the metal has functioned as a store of value, unit of account and medium of exchange.

“The Egyptians were casting gold bars as money as early as 4000 BC, each bar stamped with the name of the Pharaoh Menes,” the financial historian Peter Bernstein writes in “The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession”. Bullion played a foundational role in the monetary system from 1717, when Sir Isaac Newton, master of England’s Mint, established a price ratio between gold and silver, to 1971, when President Nixon ended the convertibility of dollars into the precious metal.

Though gold stopped underpinning exchange rates after the “Nixon Shock”, the metal still plays a part in currency markets. Central banks in emerging markets have, for instance, boosted their gold holdings in recent year.

“It is more a currency than a commodity,” said Dr O’Connor. “Everything else, to one degree or another, gets used up and doesn’t come back into the market. Gold just stays there.”

Dow Jones Newswires

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout