A misplaced faith in the power of central banks

The Fed cannot save the US economy from the coronavirus, for two reasons.

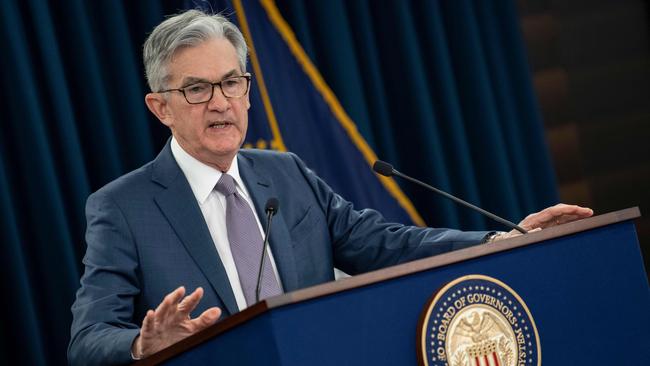

Wall Street and US President Donald Trump have begged, admonished and tweeted for the Federal Reserve to come to the economy’s rescue. On Tuesday morning, the Fed obliged.

But their faith is likely to prove misplaced. The Fed cannot save the US economy from the coronavirus, for two reasons.

First, it can’t restart factories that are missing parts as the virus disrupts supply chains, nor can it persuade worried vacationers to fly. Second, and potentially more important, central banks are losing their grip on the business cycle.

The Fed had little interest-rate ammunition with which to boost growth even before Tuesday’s cut; the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan effectively have none. The world is facing its first big shock in an era when central banks are no longer omnipotent.

The good news is that the same factors that make monetary policy less potent make fiscal policy even more so. With investors rushing to buy government bonds and driving yields down, the US and other rich governments can borrow all they need to fight the virus and recession risk without fear of driving up rates.

US recessions have historically been precipitated by rising inflation and interest rates, collapsing asset prices, or both. Central banks had the right tool kits to respond: they could lower rates or, if necessary, buy assets such as bonds or make direct loans to impaired banks, as they did during the global financial crisis in 2008 to 2009.

Since that crisis, structural factors such as low productivity growth, ageing populations and risk aversion kept economic growth and inflation low around the world, making it difficult if not impossible for central banks to raise rates. The ECB and Bank of Japan cut theirs below zero. The Fed raised its short-term interest rate target to between 2.25 per cent and 2.5 per cent in 2018, then had to cut it three times last year, to between 1.5 per cent and 1.75 per cent, because of a global slowdown and trade war. On Tuesday, it cut its benchmark rate by half a percentage point.

Central banks hoped that with time inflation and growth would firm enough for interest rates to return to some normal, positive level. The risk was always that some shock would come along to short-circuit that process.

Superficially, the coronavirus is similar to other shocks that have rocked the US or global economy in the past, from the Kobe earthquake in Japan in 1995 to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The effects are usually temporary: “supply-side” disruptions to production, travel and commerce.

Epidemics historically haven’t been disruptive enough to affect gross domestic product much.

But that probably won’t be true this time. Over time, the supply-side disruptions of pandemics have been compounded by demand-side effects: precautionary measures by the authorities, employers and individuals to avoid infection.

These behavioural effects account for 80-90 per cent of the economic hit from epidemics, according to work by Warwick McKibbin, an economist at Australian National University.

Goldman Sachs estimates 10-15 per cent of US GDP consists of services such as entertainment, restaurants, church services and public transportation that would suffer if people limit interaction and avoid large gatherings. The Fed can’t offset these effects, said its chief economist Jan Hatzius.