A disputed election: my lesson from 2000

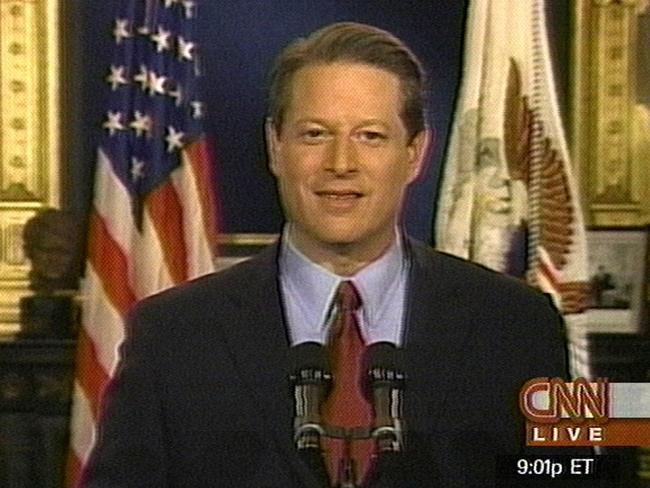

Al Gore showed me the importance of accepting an adverse outcome.

It was Friday, December 8, 2000, when, after a month of turmoil, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a statewide recount of presidential votes, a ruling that might have meant Al Gore and I had been elected president and vice-president.

But then George W. Bush’s campaign appealed to the US Supreme Court, which shocked us by agreeing to hear the case. Oral arguments were made the following Monday, and the justices handed down a decision on Tuesday night, December 12.

Late that evening, vice-president Gore called me at my home to inform me that the court had just ruled in the Republicans’ favour, but that some on our legal team believed we could go back to Tallahassee for further litigation. Did I think we should keep fighting?

My answer was born of a belief I had developed while serving as Connecticut’s attorney-general. I was, naturally, surprised, hurt and angered by the Supreme Court’s decision. Our election lawyers were still analysing the opinion; the vice-president told me some of them believed we had no further recourse, but others argued we could and should go back to Florida and ask the court there to implement their previous order for a statewide recount.

My gut said we should do the latter — when you have a plausible legal argument, you should take it to court and let the judiciary decide. Not only did I think we had a reasonable case, but there was a lot on the line for our country, and we had won the popular vote by more than half a million ballots. Al said he would think about it and get back to me quickly.

The phone rang again after midnight. “Joe,” he said, “I’ve decided to end it. The electors are meeting next week. We are a month from the inauguration. An appeal and recount in Florida would probably take at least that long, which could spark a constitutional crisis and raise serious questions about the continuity of our government. This was a very difficult decision for me, and I know it is for you, but I believe it is right and best for our country.”

Thus, as he said publicly that Wednesday: “I accept the finality of the outcome which will be ratified next Monday in the Electoral College. Tonight, for the sake of our unity as a people and the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession.”

I had counselled the vice-president differently, but I can say unreservedly that his choice was the best for our country. Today both campaigns need to take his example to heart. As uncertainty looms and lawyers make arguments about the election process in states across the country, I ask Donald Trump and Joe Biden to remember two things:

First, we are a country that abides by the rule of law. The candidates should resolve their disputes in the courts, not in the streets. Messrs Trump and Biden must make clear that violence of any kind is unacceptable and criminal.

Second, at some point this election must end for the sake of America, which both presidential candidates have pledged to put first. The litigation can’t last forever. One of these two men will be president for the whole of the country for the next four years. The other man will need to accept that outcome and counsel his supporters to do the same, and thereby put country over party and self-interest.

In Washington today, the prevailing impulse seems to be to press for every partisan or personal advantage, heedless of the damage done to the institutions of our democracy and our country. As Al Gore attested two decades ago, our leaders must remain true to the principle that our society, its leaders and its citizens must follow the rule of law and serve the national interest — especially when the stakes are high.

In the days to come, there may well be extended uncertainty and litigation. In the end, all of us will need to accept the outcome. When the process comes to its conclusion, the candidates who concede will be able to take pride, and perhaps some comfort, in having served the greater good of our great country.

Joe Lieberman was the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in 2000 and a US senator from Connecticut, 1989-2013. He is chairman of No Labels, a group that advocates a return to bipartisanship

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout