2020 race: Pete Buttigieg, the polished, genial adult in the room

In a party whose members loathe any and all Republicans, Pete Buttigieg’s advantage is that he’s everything Donald Trump is not.

Twenty years ago, a high school senior from South Bend, Indiana, won the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Essay Contest. Peter Buttigieg’s 2000 treatise for the JFK Library was a paean to — ironically as it would turn out — Bernie Sanders. The 18-year-old essayist praised then-Rep. Sanders for two reasons: He was a man of conviction and candour, willing to take tough positions and adopt the unpopular label of “socialist.” He was also “a powerful force for conciliation and bipartisanship on Capitol Hill.”

“Sanders’ positions on many difficult issues are commendable,” Mr Buttigieg wrote, “but his real impact has been as a reaction to the cynical climate which threatens the effectiveness of the democratic system.”

The prizewinning essay accurately adumbrates the campaign message of one of Mr Sanders’s 2020 presidential rivals: Pete Buttigieg. Mr Buttigieg, 38, has just left office after two terms as South Bend’s mayor and polls impressively in the Democratic primaries.

Iowa chose a new path—a choice New Hampshire can make one week from today.

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) February 4, 2020

If you're with me, chip in: https://t.co/lJXXbBjL7F pic.twitter.com/wjbAxp3xMX

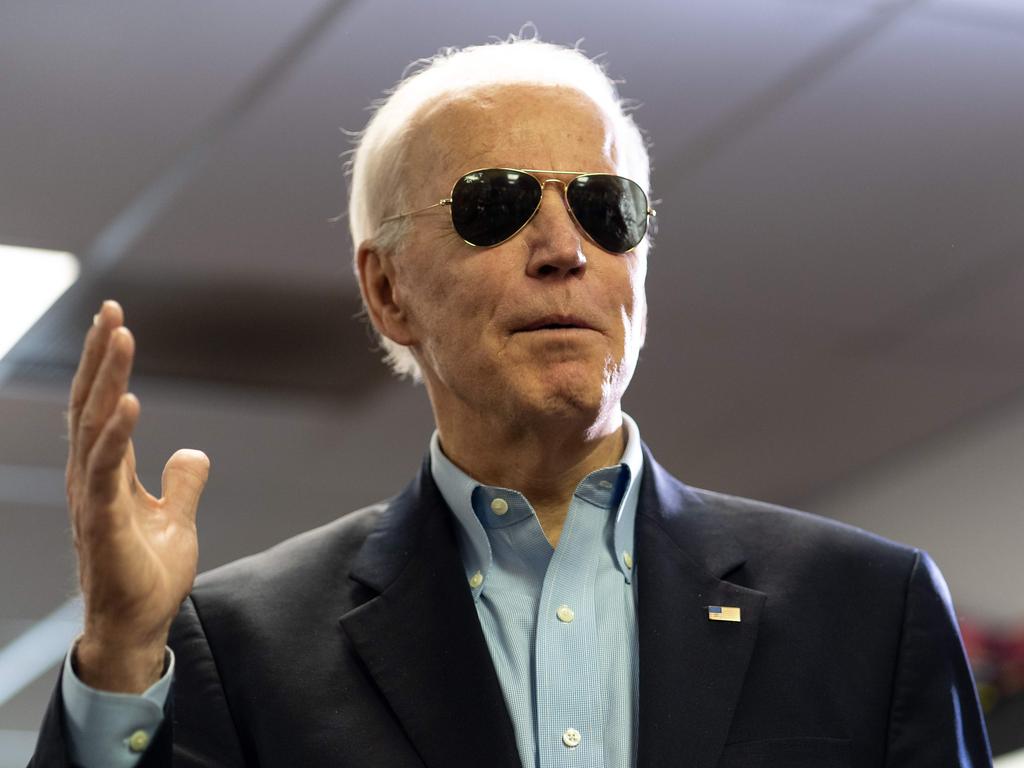

He is leading the Iowa caucus with 62 per cent of the vote counted and is either at or near the top in both the Iowa and New Hampshire primaries, though his numbers are far lower in South Carolina, where black voters favour Joe Biden by a large margin.

Mr Buttigieg’s message: After four years of division and “fighting over politics,” Americans must come together by embracing an ambitiously progressive agenda. That two-step pitch — national unity plus left-wing policies — may sound contradictory or self-defeating, but it isn’t unprecedented.

It mimics the rhetoric of left-wing solidarity Mr Sanders has long used to great effect. More conspicuously, it recalls Barack Obama’s message of national unity and unapologetic progressivism. As I listened to Mr Buttigieg deliver campaign talks to audiences across southern New Hampshire last week, I was constantly reminded of Mr Obama.

Like the 44th president, Mr Buttigieg often speaks of the presidency as if its constitutional role were to create harmony in the populace and to heal wounds inflicted by hate and division.

“The purpose of the presidency is not to glorify the president,” he told an audience in Nashua. “It’s to unify and empower the American people.”

In Manchester, he said the US needs a president “who will leave us more unified than before — that will galvanise and not polarise the American majority.”

The pundits didn’t see our coalition coming.

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) February 4, 2020

This president won't see it coming either. pic.twitter.com/LeBcaa7w3Q

His delivery often falls into an Obama-like cadence, with long sentences punctuated by a few stressed words, concluding in a resonant line: He wants to make America “a country where your race has no bearing on your health or your wealth or your life expectancy or your relationship to law enforcement — to send a message that this is a country where everybody belongs and hate has no home.”

Mr Buttigieg frequently feints to the right, though to my mind not as convincingly as Mr Obama did. “Freedom sometimes means having government step up,” he says in every stump speech, “but sometimes it means getting government out of the way.” You’re expecting something about onerous regulations or burdensome mandates, but he goes on to say that “freedom means getting government out of the business of telling people who they ought to marry” and keeping government from “dictating to women what their reproductive health-care choices ought to be.”

Mr Buttigieg appears to cultivate visual similarities to Mr Obama, too. Notably young and thin, the former mayor always appears jacketless with sleeves rolled up, even during a New Hampshire winter.

Sometimes Mr Buttigieg sounds as though he’s running to succeed George W. Bush rather than the intermittently isolationist Donald Trump.

“Patriotism,” Mr Buttigieg likes to say, “does not mean unnecessarily starting an endless war.”

Mr Buttigieg, as readers of his 2019 memoir, The Shortest Way Home, can easily perceive, has wanted to be president for a long time. He was raised in a bookish and politically liberal home: His father, a professor of literature at Notre Dame, translated the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks.

He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard before attending Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. Later he worked for the global consulting firm McKinsey as a kind of economic-development technocrat. He ran for Indiana treasurer and lost badly in 2010, then successfully for mayor of South Bend in 2011. While mayor he served in the US Navy Reserve.

His presidential campaign’s theme of unity and solidarity has some logic. Polarisation is on everybody’s mind. It’s the subject of a thousand books and articles. The trouble is that polarisation is polarising: Everybody thinks it’s the other side’s fault.

Many Democratic voters are so full of loathing for the GOP that, apart from Mr Biden, the leading Democratic candidates appear scared to say anything remotely favourable about a living Republican. Mr Buttigieg cleverly puts it negatively: “You can’t love the country if you hate half the people in it.”

Last May Mr Buttigieg took part in a town hall hosted by Fox News in the western New Hampshire town of Claremont. Barack Obama outpolled Mitt Romney there by more than 20 points in 2012, but in 2016 Claremont plumped for Mr Trump. The town has seen a three-decade exodus of industry and responded favourably to Mr Trump’s promises of industrial revitalisation. Progressives sharply criticised Mr Buttigieg for taking part in a Fox News event, but it was a savvy move from a candidate who understands he has to win back areas that abandoned the Democrats in 2016.

He revisited the town on his latest tour through New Hampshire and spoke to a crowd of perhaps 1,100 in a packed high-school gymnasium. He began his remarks by recalling the flak he took for the Fox town hall. “The reality is,” he said, that “our message and our values and our policies will do right by individual Americans and their families — no matter what cable news TV station they watch.” It’s hard to imagine Elizabeth Warren saying this.

Every political campaign involves abstract and slippery verbiage, but you frequently come away from a Buttigieg talk wondering what exactly the candidate meant. He says, for example, that he intends to “use the powers of the presidency to answer the crisis of belonging in this country.” He elaborates: “So many people are being made to feel they don’t belong, in so many different ways — because of your race, or religion, the language you speak at home, or disability, or who you love, or where you come from … People are being told, ‘There’s not a place for you.’ We have to build a sense of belonging that reassures everybody that they are at the heart of the American project.” Will the former mayor of South Bend liberate us from the human condition?

You could have asked a similar question of Mr Obama in 2008, when he was a first-term senator from Illinois and described his securing the support of enough delegates to assure him of the Democratic nomination as “the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.”

The idea that Mr Buttigieg can duplicate Mr Obama’s political wizardry is not preposterous, but there are at least three reasons to doubt it. First and second, unlike in 2008, the economy isn’t in free fall and the US isn’t engaged in a gruelling, unpopular war. Third, Mr Buttigieg is a white man, and his party’s ascendant progressive caucus is prejudiced against white men.

Mr Buttigieg can lay claim to one minority status: He is gay. He announced his sexual orientation in 2015 and married a man, Chasten Glezman, in 2017. Still, it isn’t entirely clear that his homosexuality will work to Mr Buttigieg’s electoral advantage. As one moderate Democrat at an event in Wolfeboro put it to me, “Some people won’t like the fact that he’s gay. I don’t mind, but some people won’t like it.” Imagine a Democrat in 2008 saying he “doesn’t mind” that Mr Obama is black.

The Democratic Party is solidly pro-gay, but some African-Americans have openly expressed apprehensions, and the comparison Mr Buttigieg sometimes draws between being black and being gay — “I know what it’s like to feel your community has been left behind” — has gone over poorly among South Carolina blacks.

Mr Buttigieg seems to sense that his sexual orientation may be a liability as well as an advantage, and he occasionally plays it down. During his five-month stint in Afghanistan, he says, his fellow servicemen “could not have cared less about whether I was going home to a girlfriend or a boyfriend.” That isn’t hard to believe, but civilians can be equally blasé. For many people, including liberals, voting for a gay man doesn’t afford the sense of righteousness they felt when they cast ballots for the first black president.

Mr Buttigieg does have one clear advantage. To a greater extent than perhaps any other Democratic candidate, he is everything Donald Trump is not: polished, genial, well-read, articulate.

When I asked voters at his campaign events why they were interested in Mr Buttigieg, almost every one said something about the candidate’s pleasing deportment. “He’s the adult in the room,” a man in Wolfeboro told me. “I like the way he carries himself,” said the woman standing next to me in Manchester, whose T-shirt bore a pronunciation guide: “BOOT EDGE EDGE.” A woman in Nashua, by appearances a college student, said that when Mr Buttigieg opens his mouth, “you don’t have to worry.”

Patricia Barry, principal of Stevens High School in Claremont, introduced Mr Buttigieg by praising his measured bearing. “I want to know that when I turn on my TV,” she said, “I can be proud of my president.” Such remarks call to mind that prizewinning essay from 20 years ago. You don’t win an essay contest by persuading your readers or winning an argument; you win it by impressing the judges. If the 2020 election were an essay contest, Mr Buttigieg would win easily.

The Wall St Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout