The chief executive of Rio Tinto, Simon Trott, announced he would travel to China this week. Fortescue not far behind, with CEO Fiona Hick flying to China next month.

The decisions made in the coming year may determine the long-term shape of Australia’s iron ore industry and its ability to drive national prosperity.

The Chinese clearly recognise that in a low-carbon world a new approach to steelmaking will be required and fascinatingly, just as the richness of Australia’s hematite iron ore attracted first Japanese steelmakers and then Chinese, now another feature of Australia is drawing the Chinese in our direction: the availability of abundant solar or wind energy for “green” iron or steel production.

Petroleum giant BP has taken a 40.5 per cent interest in the Asian Renewable Energy Hub in outback Western Australia, which plans to develop up to 26 gigawatts of wind and solar power capacity starting around 2029.

The major Australian investor is Macquarie bank.

The base plan is to use that power for Asian markets and for the mining industry.

The project has been delayed by environmental concerns over wetlands. At this stage very little of the power and/or hydrogen has been contracted.

The potential availability of that power/hydrogen will be a major attraction for Baowu Group.

The conventional path to “green” iron and steel is for renewable power to be used to extract hydrogen from water.

There are a number of difficulties.

Orica, which requires hydrogen for ammonium nitrate explosives, says that with present technology extracting hydrogen from water is much more expensive than extracting it from natural gas, so both the “green” steel and explosives industries are hoping for a technological breakthrough.

In the current conventional “green” steelmaking process, iron ore is first reduced to “green” iron using hydrogen.

That green iron is then fed into a renewable-powered electric-arc furnace to make steel with low to zero emissions.

But unfortunately for Pilbara hematite ore miners BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue and Hancock, that base steel making method is better suited to magnetite ore or the manufactured pellets with high iron content that Rio makes in Canada and Vale makes in Brazil.

Australian hematite ores are not well suited to green steelmaking because hematite often has impurities such as silica, alumina and phosphorous. Unlike conventional steel furnaces, electric arc furnaces cannot tolerate those impurities, so new technologies must be found if Australia is to produce green steel using hematite.

Magnetite ore on current technology is much more suited to electric arc furnaces.

Fortescue’s $US3.8bn iron bridge magnetite project is scheduled to deliver its first product this year. Magnetite iron ore mines have been developed by Clive Palmer and Mineral Resources.

Gina Rinehart is planning a magnetite mine near Port Hedland and has substantial magnetite at Mount Webber in Western Australia.

There is also considerable research taking place in both Australia and China on better ways of using wind and solar power than using it to extract hydrogen from water. One such method involves the use of goethite iron ore. CSIRO research helped reveal that if goethite is included in the mix of materials used in conventional blast furnaces, less coking coal is required.

The goethite molecules are a combination of iron, hydrogen and oxygen.

The conventional steelmaking process releases the hydrogen in the goethite molecule, which reduces the need for carbon. But steel produced that way is certainly not “green steel”.

A number of companies – including Sumitomo in Japan, the Rio Tinto-BlueScope research team and Haoma, in conjunction with a major university – are separately working on new ways to make “green” steel.

One of those systems is a combination of goethite, hematite and magnetite that could be smelted by a continuous flow induction furnace pipe at much lower temperatures than a conventional blast furnace.

The smelting process would use gas, but the carbon emissions are slashed and the costs reduced because the process takes place at much lower temperatures and releases the hydrogen in the goethite (replacing coal), which is far more economic than making hydrogen separately from water.

The potential of goethite ore was highlighted when former BHP director Malcolm Broomhead purchased 9 per cent of the Morgan family’s Haoma, which has large goethite deposits in Australia that do not contain asbestos. It also has substantial reserves of high-grade magnetite iron ore.

In the 1990s, Broomhead transformed the old North Broken Hill company into the lowest-cost iron ore producer in Australia.

North was taken over by Rio Tinto. Soon after, he became the CEO of Orica, which he transformed into a leader in world explosives.

There are many other research projects being undertaken to lower the costs of green steel. Fortescue has a major project, while China has been buying low grade hematite at prices that are too high, given conventional steelmaking methods.

It may have achieved a breakthrough.

Australia needs to get on top of China’s technological developments before doing long-term deals.

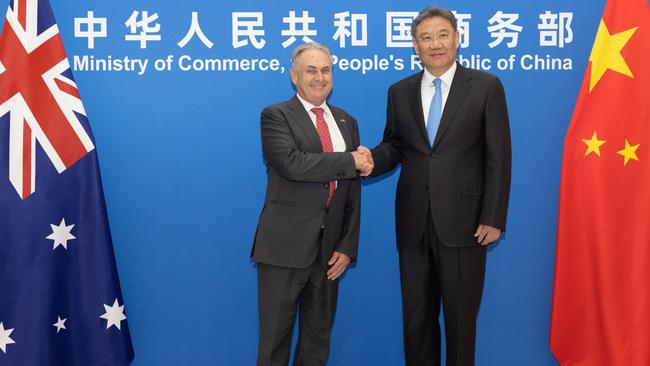

The export of iron ore has been a key pillar of Australian prosperity for the last half century. In a shock announcement during the visit of Trade Minister Don Farrell to China, the largest Chinese steelmaker, Baowu, announced it was looking to make “green” iron and steel in Australia, Brazil or Canada.