Why your colleague’s avatar looks nothing like them

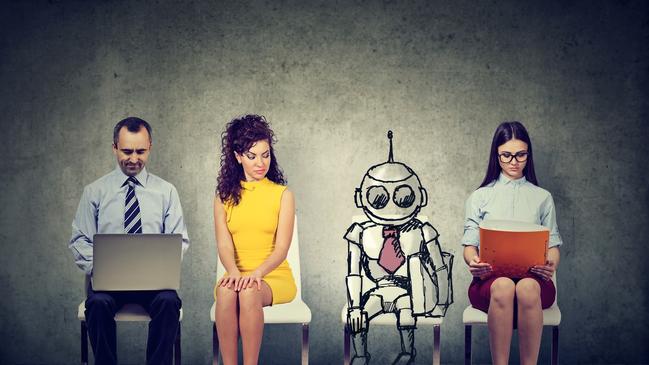

Get used to dealing with avatars - online and in the office.

As the push to work in the metaverse continues, Australians may soon have to recognise their co-workers by more than just their physical appearance.

Avatars, which have been described as the “skin” that users wear to interact in virtual platforms, are increasingly being pushed upon consumers on social media, under a move experts liken to a “gateway drug” into the metaverse.

In general, avatars vary only marginally from a person’s photograph, with slight modifications of skin tone, facial structure, length of nose or eyebrow shape.

Internet studies professor Tama Leaver says a lack of ability to express one’s self could in some circumstances lead to people presenting online appearances with some features omitted.

He says modern avatars are being increasingly introduced with a one-size-fits-all approach.

“The thing with these sort of styled-down avatars is you can’t often show your worst self. I don’t think it would be possible to make, say, a genuinely obese avatar if you happen to be that way in real life,” Leaver says.

Today’s options are less accommodating than the earliest versions of metaverse platforms such as Second Life, released in 2003, which allowed users to interact in forms other than human.

“In Second Life you weren’t even limited to say humanoid form, whereas the avatars that we tend to see today are actually comparatively incredibly dull,” Leaver says.

WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat all allow users to represent themselves with avatars which can be used like emojis to display certain feelings and responses.

Even Apple, a company yet to formally disclose its metaverse plans, is in on the avatar trend, allowing iPhone users to create a digital character that can be set as their contact image and share to anyone with the user’s phone number.

As to whether an avatar accurately represents its owner, there’s little or no authority. But the limited scope could be part of a larger bid to get consumers to pay a premium for any kind of accessories and personalisation, Leaver says.

“One of the things people who are rolling out avatars would like is for people to pay for other accessories,” Leaver says, likening the push to that of the game Pokemon Go, which sees players pay to change their avatar’s hair style, poses and outfits.

The use of cartoon characters to represent online personas is not new.

During the pandemic, NFTs (non-fungible tokens) were commonly used as profile pictures across Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Social media platforms cottoned onto the trend a little too late, with Instagram introducing the ability to display NFTs in May last year. Compatible wallets included Rainbow, MetaMask, and Trust Wallet. Coinbase, Dapper and Phantom were set to follow.

The integration arrived one month after Sina Estavi, the founder of a Malaysia-based blockchain company who purchased an NFT of Jack Dorsey’s first tweet for $2.9m, put it up for sale for $14,000.

Leaver says cartoon-like characters are used by companies as a way to market their brand while mitigating the risk of scandals with influencers and content creators. These extensions of brand are known as virtual influencers.

Some online virtual influencers have amassed millions of followers who regularly check social media platforms for updates on the lives of these computer-generated brand extensions. But virtual influencers are typically controlled by teams of 10 to 15 people rather than by artificial intelligence, Leaver says.

A similar kind of influencer known as a VTuber exists on YouTube.

“These are YouTubers who use an avatar interface recorded in real time to drive a character,” Leaver says. “They’ve been around for at least five years, possibly longer.”

Leaver says he expects a greater push of avatars.

“Avatars are a gateway drug to the metaverse,” he says.

“They are sort of the skin, if you like, that people wore to interact in that old virtual environment and what companies are trying to do now is get us used to looking at each other and seeing avatars.

“We know that the metaverse in its initial instances will be very cartoonish. And we know that, if we’re going to accept that as a place to live, work, play, then we’re going to get used to seeing other people through those sort of cartoonish eyes.”

As to how the characters will affect the way we think and feel, Leaver says: “There have been studies in some games where people are highly invested in avatars and it can be quite emotionally damaging if the avatar is messed with by a third party.

“It really depends on the person and their relationship with the avatar and whether they see it as part of themselves, their psychology, or the way in which they interact socially with the world.”