What’s the deal with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez?

She’s young, radical and has a seat in Congress. And she reckons we’ve got the economy all wrong. Should we care?

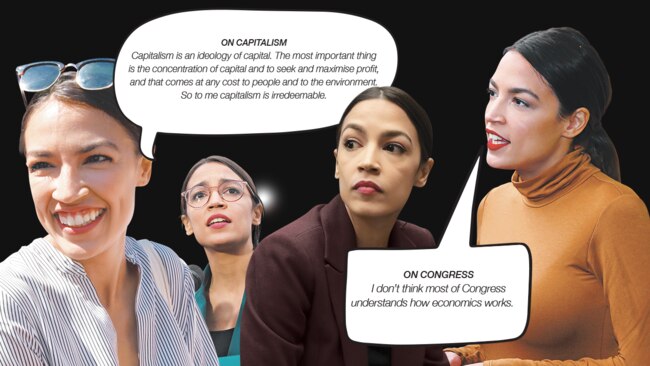

The landing of 29-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the US Congress has generated not so much a splash as an earthquake. She is as outrageous to Republicans as Donald Trump is to Democrats, and as much of an untameable challenge to the leadership of her own party as he is to his. The economics establishment has united in horror at the scale of her deficit-funded program.

Enter “Ocasio-Cortez” and “economics” into Google and you are inundated with vitriol: Shows basic ignorance; Attractive, glib, energetic, but she has zero understanding of history or economics; Needs to learn the ABCs of Economics 101 before espousing her outrageous opinions; A kindred spirit to (Venezuela’s) Nicolas Maduro – and so on, across most of the 15.2 million responses.

Ocasio-Cortez arrived in Washington in January, having won her New York seat after ousting the third most senior Democrat congressman in a primary battle. Born in the Bronx to a struggling Puerto Rican family, she made it to Boston University with a scholarship and loans. Her economics degree is often cited by her critics as proof of the inadequacies of a university education.

She worked in a call centre for Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign when she was just out of school, and was plucked from a waitressing job in a Mexican restaurant last year for a political career by the “Brand New Congress” movement, created by the millennial fan club of 2016 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. She is bright, articulate and fresh in a way that Obama was when he burst onto the American political scene, but she is a generation younger and she brings an unconstrained radicalism to the heartland of American politics.

She has views. The top tax rate should be raised from 37.5 per cent to 70 per cent for incomes above $10 million. Prisons should be closed. Health care should be free. More fundamentally, the government should put an end to poverty, with every family guaranteed a minimum income. “I don’t think any person in America should die because they are too poor to live,” she says.

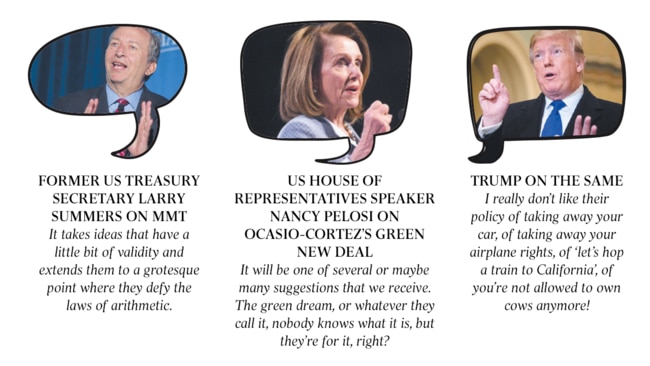

She has brought her ideas together in a resolution before Congress calling for a “Green New Deal”, echoing the New Deal launched in 1933 by president Franklin Roosevelt to lift the US economy out of the Great Depression. Ocasio-Cortez’s deal maintains that the US should shift to net zero carbon emissions over the next decade with all use of fossil fuels to generate electricity and power motor vehicles to be abolished. There would be a federal jobs guarantee, free higher education and health, very fast trains and much more. The plan is uncosted but would be in the trillions of dollars a year.

And how would it all be paid for? Here is the answer, contained in a briefing note from her office, that has the economics establishment in a frenzy: “We will finance the investments for the Green New Deal the same way we paid for the original New Deal, World War II, the bank bailouts, tax cuts for the rich, and decades of war – with public money appropriated by Congress.”

Ocasio-Cortez is careful about her support for what she knows are inflammatory propositions, and the briefing note was withdrawn shortly after it was issued. But she argues that the idea that government does not have to balance its budget and that surpluses actually hurt the economy needs to be “a larger part of our conversation”.

Of course the US budget is already deep in debt, with this year’s deficit expected to reach $US900 billion ($1.3 trillion, or about 4 per cent of GDP). Economist John Maynard Keynes argued for deficit spending to support an economy in a downturn, but Ocasio-Cortez is talking about a more far-reaching idea.

She supports what has become known as Modern Monetary Theory, which holds that the only constraint on spending for a government which controls its own currency is inflation, which can be managed by varying taxes.

MMT has been quietly circulating in left-wing economics academic circles for decades. One of its advocates, Stephanie Kelton from New York’s Stony Brook University, was Sanders’ economic adviser. The director of the University of Newcastle’s Centre of Full Employment and Equity, Bill Mitchell, is one of its founding theorists.

Its origins can be traced to the early 20th century economist Georg Friedrich Knapp, who argued that money had no intrinsic value but was the unit of account that governments would accept as payment of their tax obligations.

‘I don’t think any person in America should die because they are too poor to live’

Unlike a household, a government that can issue its own currency is never in a position where it cannot finance something. “Any currency-issuing government can purchase anything that is for sale in that currency including all idle labour,” Mitchell says. It follows that the existence of unemployment is a political choice. The government can choose whether it finances its purchases through raising taxes, entering a debit with the central bank or issuing bonds to match its spending.

Mitchell says MMT is not a policy prescription – rather it simply describes the way monetary and fiscal policy actually work. It has been a choice of governments to make central banks responsible for monetary policy and charge them with meeting inflation targets. It could equally decide to control inflation itself, while charging the central bank with managing public debt.

Although currency-issuing governments face no financial constraints, they are limited by the real world. To the extent that their spending and that of the private sector is greater than the available supply, inflation will result. Faced with rising inflation, a government might raise taxes to reduce demand or reduce its own spending.

Mitchell says a program on the scale of Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal could not simply be delivered by the government paying to deploy existing idle resources in the economy and would require politically challenging decisions to divert resources already being used.

But far from there being anything inherently wrong with government deficits, he says they enable the non-government sector (both business and households) to achieve their desire to save. If governments ran persistent surpluses, the non-government sector would be left managing matching deficits.

While the theory has been lurking in the academic halls, it has burst into the policy arena partly because of the

endorsement by Ocasio-Cortez and others on the left of the US Democrats, notably Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. It now has a political platform.

Although the British Labour Party’s Jeremy Corbyn has captured similar millennial support to Sanders, the party itself remains fiscally conservative, backing budget rules to ensure current spending is covered with taxes. MMT has gained no traction with the Australian Labor Party, where Treasury spokesman Chris Bowen is promising larger budget surpluses than the Coalition.

Its US following reflects a view on the left that the monetary and fiscal policies of the past 20 years are not working. The single-minded pursuit of low and stable inflation under former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan is seen to have created the conditions for the global financial crisis. A decade on, inflation and wages growth are still below their targets.

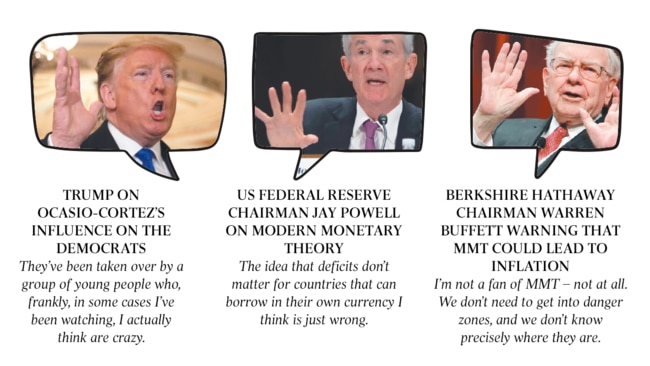

The perception that living standards have stagnated while inequality has increased since the crisis is at the root of rising support for both the left of the Democrats and the right of the Republicans under Donald Trump.

Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell has acknowledged that the Fed is affected by the “declining trust in public institutions around the world”, and has embarked upon a review of its inflation targeting strategy to see if the tools it is using are still appropriate. The review will include town hall meetings around the country and a major conference inviting both academic and non-academic contributions.

Powell emphasises he does not envisage major change – he favours “evolution rather than revolution”. But the review highlights the Fed’s recognition of the challenge to its orthodoxy.

In congressional testimony last month, Powell attacked MMT. “The idea that deficits don’t matter for countries that can borrow in their own currency I think is just wrong,” he said, while acknowledging that he had not read any of the theory.

Larry Summers, who has been one of the most trenchant critics of post-crisis monetary and fiscal policy, dismisses MMT as “voodoo” economics, saying: “It takes ideas that have a little bit of validity and extends them to a grotesque point.” Summers says government needs to be wary of saddling itself with unsustainable debt. “I don’t know what so-called Modern Monetary Theorists have in mind, but the idea that we should abandon the tool of monetary policy and somehow make the central bank subservient – seems we’ve seen that movie before,” he told Yahoo Finance.

And yet the sands are shifting. Former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard recently published a paper that is receiving widespread attention showing that governments can issue debt without having to later raise taxes, provided interest rates are below the economy’s growth rate. He shows this has been the case for most of post-war US history and also holds in other advanced countries. “Put bluntly, public debt may have no fiscal cost,” he says, affirming one of the tenets of MMT.

Blanchard nevertheless says he does not accept MMT’s premise that public debt has no impact on economic welfare, and has said he is working on a broader critique.

Having formally said no more than that MMT should be part of a “broader conversation”, Ocasio-Cortez is not engaging in the theoretical debate. But she does argue, with that uniquely American style for turning a noun into a verb, that “the idea that we’re going to austerity ourselves into prosperity is so mistaken”.

She told Business Insider magazine that congressional members on both sides failed to understand the “transformative power of the purse” they possess.

“There has almost never been a period of substantial economic growth in the United States without significant investment,” she said. “And no investment pays off within the same cycle. No investment pays off within the same year – especially a governmental investment. Even businesses don’t work that way. In a modern, moral and wealthy America, where we have the capacity to ensure that every American can have health care, an education and access to dignified housing, we should try to do that as a society by whichever means we can.”

-

View from the economists

Adam Creighton looks at ten of the world’s best economist and some alternative approaches to understanding the system.

Anat Admati

The global financial crisis seriously embarrassed the economics profession, which had ignored the fateful build-up of risks in banking. Anat Admati, a professor of finance at Stanford University, soon provided a clear comprehensive explanation and solution in her best-selling 2013 book The Bankers’ New Clothes (written with Martin Hellwig). Banks had taken on too much debt and should reduce their leverage significantly to boost confidence in the financial system and reduce the implicit subsidy that flows from government to banks. She argues persuasively that large banks have captured the regulators in most countries.

-

Angus Deaton

The United States is such a rich country it’s easy to forget about its pockets of misery. Angus Deaton, professor at Princeton University, was awarded the Nobel prize in economics for his analysis of consumption, poverty and welfare across countries, especially the United States and India. He famously showed how life expectancy of non-Hispanic whites, especially men, had started to decline in rural regions of the United States, reversing a centuries-long trend.

-

Luigi Zingales

The University of Chicago became famous for its slew of free-market economists, from Frank Knight to George Stigler. Luigi Zingales, a professor of economics at Chicago, argues the unpopular aspects of the the free-market system, especially the response of policymakers to the financial crisis, typically reflect “crony capitalism” – the power of firms and their managers to influence government policy against the public interest. More recently, he’s argued for heavier regulation of Facebook and Google to curb their power.

-

Richard Holden

Unlike their American peers, Australian academic economists have been reluctant public commentators. The impeccably credentialled UNSW economics professor Richard Holden (PhD at Harvard, stints teaching at Chicago and MIT) breaks the mould, contributing regularly on policy debates including a policy paper in 2015 on changes to negative gearing that influenced Labor’s policy platform. His recent research focuses on the timing of political bombshells: trustworthy politicians tend to release valuable information long before voting day.

-

Jonathan Tepper

A London-based investment manager rather than an economist, Jonathan Tepper – with fellow Australian investor John Hempton – called the Australian property market an ominous bubble back in 2016, when Sydney and Melbourne prices were still galloping ahead. More recently he’s penned The Myth of Capitalism, a book which argues powerfully for a renaissance of anti-trust activity by governments to curb the power of large companies, especially Facebook and Google.

-

Alan Auerbach

Donald Trump’s 2017 tax reforms were almost revolutionary. The Republican party had originally adopted what’s known as a “destination-based cash flow tax” on companies, based on a proposal in 2010 by Alan Auerbach, professor at University of California, Berkeley. While Trump ultimately balked at the idea of taxing businesses’ cash flows rather than profits – and allowing tax deductions only for purchases made domestically – Auerbach’s many tax contributions will guide the gradual shift away from taxes on company profits, which globalisation has made costly to administer and design.

-

Paul Romer

Most macroeconomists don’t publicly mock their own discipline. Yet Paul Romer, a former chief economist of the World Bank and professor at New York University, recently slammed economists’ use of theoretical and mathematical models to explain how economies worked. He resigned suddenly from the World Bank last year after suggesting some of its staff could be biased. It didn’t hurt him – he received the Nobel prize last year for his analysis of how countries become rich. It wasn’t all about saving to buy better machines, but investing in education to improve “human capital”.

-

Mervyn King

Central bank governors tend to fade away after their tenures, hibernating on bank boards and enjoying extraordinary pensions, yet Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England for a decade to 2013, wrote a forceful critique of the hand that fed him. His best-selling 2016 book The End of Alchemy argued the financial system had changed very little as a result of post-crisis reforms, while huge trade imbalances between countries had undermined the global economic system. King’s 1979 book The British Tax System, with John Kay, is in its fifth edition.

-

Nassim Taleb

A New York-based former trader and mathematician, Nassim Taleb would be insulted to be grouped with economists. But his series of popular books attacking the profession for its hopeless forecasting, and bankers for their recourse to government subsidies, have become must-reads. The Black Swan (2007), Antifragile (2012) and Skin in the Game (2018) have put a dent in both groups’ confidence.

-

Dani Rodrik

The global backlash against trade stretches from the UK’s Brexit vote to Donald Trump, who has slapped tariffs on China and torn up a nascent Trans-Pacific Partnership. Dani Rodrik, a professor of economics at Harvard, has explained the populist revolt against free trade and investment, stressing the benefits aren’t shared equally among groups within countries. He’s long argued that manufacturing isn’t just another sector, but critically important given its ability to absorb large numbers of workers.