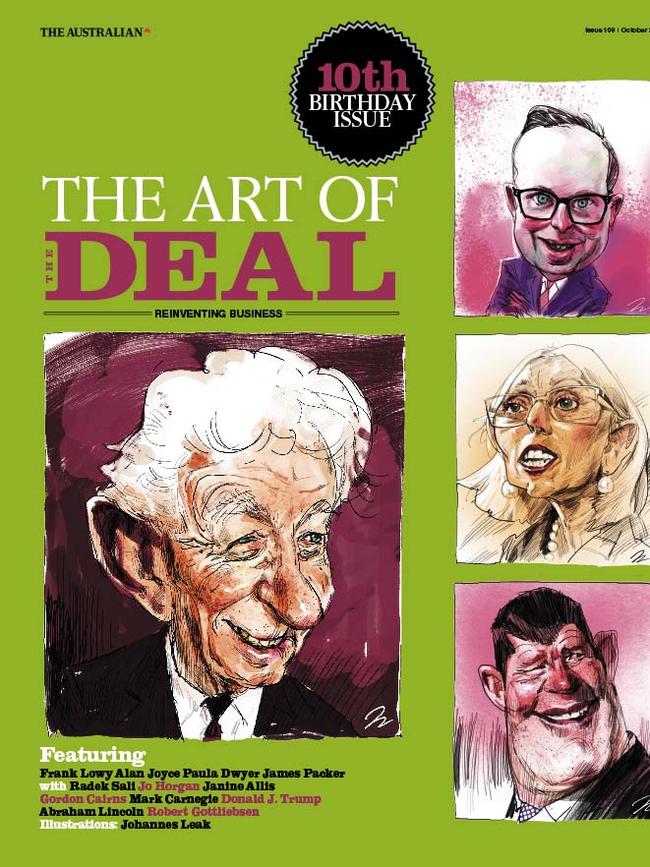

The art of the deal: The 10 worst Australian business deals since the GFC

There have been plenty of disastrous decisions that cost companies – and their shareholders – dearly.

It was former Channel Nine boss David Gyngell who best summed up the art of good deal-making. “We all feel like losers today,” Gyngell observed in 2012, after agreeing to pay double the price for broadcast rights to the National Rugby League – $1.15 billion. Nine and its partners Foxtel and Telstra had to give something away to have a chance of winning the ratings battle, even if the hefty price tag virtually guaranteed they would lose money on the match coverage.

The worst deals, though, have asymmetric outcomes – a winner and a loser. Toll Holdings’ sale to Japan Post for $6.5 billion in 2015 was a huge winner for Toll shareholders but a disaster for the buyer, who two years on wrote off $4.9 billion of the value it paid and sent the recently floated post operator to a loss.

For that reason the deal earns a spot among the decade’s worst deals. The 10-year stretch that began with the global financial crisis and was marked by record low interest rates, successive booms in commodity prices and the rise of big tech has also been littered with poor decisions. The deals have cost shareholders dearly, ended corporate careers and, in the worst cases, proved terminal for the company.

- Thursday: The 10 best deals since the GFC

1. Rio Tinto’s purchase of Riversdale for $US3.7 billion, 2010

The sheer scale of the resources boom fuelled by China’s rapid and ongoing development produced torrents of cash for the big miners, and an insatiable thirst for the next big project to satisfy its demand for commodities. Rio Tinto was far from alone in executing poor deals in its search for the next company maker. In 2007 it paid $US38 billion for Alcan, in part to ward off attention from BHP Billiton, and then proceeded to write off 75 per cent of the value. But the Riversdale saga stands out among a bad crop executed by one of the world’s leading resource companies.

After buying the relatively unknown company to get hold of its hard-coking coal prospects in Mozambique for $US3.7 billion in 2010, Rio would sell the project five years later for just $50 million. The 13 billion tonnes of reserves claimed by Riversdale turned out to be closer to three billion tonnes. Rio’s plans to transport 30 million tonnes a year of production by barge down the Zambezi River was blocked within a year of acquisition, and a year later a senior executive told then chief financial officer Guy Elliott the project had “no commercial value”.

Three years after it was sold, the US Securities Exchange Commission charged Rio, Elliott and chief executive Tom Albanese (above) with fraud for raising billions of dollars from investors without disclosing the worsening position of Riversdale. Authorities in Australia and the UK later joined in. Rio and the duo have strenuously denied the charges.

2. BHP Billiton’s push into the US shale market, $US40 billion, 2011

Former BHP Billiton chief executive Marius Kloppers will be remembered for the scale of his ambitions. Within months of taking the reins at the Big Australian, he had launched a takeover bid for Rio Tinto. When thwarted there, he hatched a deal to form a joint venture of the two iron ore giants’ Pilbara operations, but it was frustrated by regulators. And he conducted a long and fruitless campaign to secure the world’s biggest potash miner, Canada’s Potash Corp.

For all the energy Kloppers expended, the only big deal he was able to close was a push into the booming US shale market, with the $US15 billion takeover of Petrohawk and the $US4.75 billion purchase of Chesapeake Energy’s Lafayette shale gas prospects in Arkansas. Made at the top of the market, with oil prices at $US120 a barrel, the deals were aimed at giving BHP a fourth leg in energy to complement its leading positions in iron ore, copper and coal. With added exploration and bolt-on acquisitions, BHP was estimated to have spent $US40 billion by the time the oil price corrected back to $30 a barrel, as OPEC attempted to curb the US shale industry with overproduction.

Under pressure from hedge fund Elliott Management, Klopper’s successor, Andrew Mackenzie, finally agreed to sell the assets to a unit of oil major BP for $US10 billion. Along with roughly $10 billion in free cash flows over the life of its ownership, that means BHP halved its money on the deal, ripping up $US20 billion of shareholder funds.

3. Slater and Gordon’s purchase of UK litigation group Quindell for $1.3 billion, 2015

It was a delicious irony for directors and executives who have been on the wrong end of class actions launched by their most famed local exponent. Law firm Slater and Gordon last year settled an action brought by rivals Maurice Blackburn for shareholders who lost their dough buying shares in the company because of its purchase of UK litigation group Quindell.

The payment – $36.5 million – from directors’ and officers’ insurance was meagre relative to the destruction caused.

The $1.3 billion purchase in 2015, from a company described by hedge fund Gotham City Research as “a country club built on sand”, spawned a capital raising for $890 million before disaster struck. After the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority started an investigation, Quindell was forced to restate a profit to a loss and Slater and Gordon, the first stockmarket-listed law firm in the world, faced scrutiny for the way it accounted for work in hand. Shares collapsed from $8 to 8c before hedge funds bought up $500 million of bank debt and converted it to majority control of the company.

4. John B Fairfax’s buyout of family members’ stake in Marinya Media, 2008

Call it the curse of Fairfax. In 2007, John B Fairfax (above) made a triumphant return to the newspaper company that bears his family name. His Marinya Media had used $20 million of the proceeds from cousin Warwick’s ill-fated 1987 buyout of John Fairfax to buy out Rural Press. Having done a great job building up that company, he sold it to Fairfax in a scrip deal that delivered Marinya a 14 per cent stake in the merged group worth $1.1 billion.

But a February 2008 buyout of the 68 per cent of Marinya held by other family members was secured by a $170 million margin loan against Fairfax shares, worth $4 apiece. As the global financial crisis unfolded short-sellers attacked, hoping to trigger forced selling, causing a board falling-out with chairman, the late Ron Walker. Fairfax shares continued their descent, and Marinya later diluted its stake to just under 10 per cent by not taking up a rights issue. It eventually sold out on Armistice Day, November 11, 2011.

At 85c a share – a discount to the 92c market price – John B had dusted $900 million and the family left the business once again.

Nine Entertainment, once the fiefdom of fierce rivals the Packers, is now buying Fairfax for 94c a share in a takeover that will see the family name disappear from the company.

5. Allco’s buyout of Rubicon, 2008

The global financial crisis made mincemeat of anyone with excessive leverage and in Australia its most celebrated victim was Allco Finance Group, chaired by the late David Coe.

In November 2008, at the height of the crisis and less than a year after its merger with the $5 billion Rubicon property trust empire of Gordon Fell, Allco was placed in receivership. It’s a moot point whether it could have survived had it not bought out the remaining 80 per cent of Rubicon for $263.5 million. Both Allco and Rubicon relied on being able to finance billions of dollars in loans at very fine margins, and when credit markets seized up after the September 15 collapse of Lehman Brothers, the companies were doomed.

The merger drained $70 million in cash from Allco into the personal accounts of Coe, Allco director David Cooper and Fell at precisely the wrong time. Rhodes Scholar Fell’s $35.89 million share of that helped him settle on the then record residential purchase of Point Piper mansion Routala for $28.7 million.

6. TPG’s float of Myer, 2009

It’s a mark of how poorly the $2.4 billion float of department store chain Myer by TPG Capital has performed that nearly 10 years on it remains a cautionary tale for investors. Led by Ben Gray, TPG made out handsomely, trading in and out of the 61-store Myer chain in less than four years. As of mid-September, shareholders who bought into the November 2009 float at $4.10 a share had lost 90 per cent of their money, with the shares at just 41c.

Gray and co unquestionably did an outstanding job for their private equity backers. They bought Myer from the listed Coles Myer in 2006 for $1.4 billion and sold it back to the public for $2.4 billion in 2009. In between, they sold its flagship properties and more than recouped TPG’s outlay, and spent more than $300 million overhauling logistics. But they brought it to market more than a year before their 50-month turnaround plan was completed, and left investors with a company that has been unable to grow sales and profits or recover its issue price.

The tax man failed in an 11th-hour bid to recover $680 million in tax and penalties on the float profit spirited out of the country just days afterwards. Myer, meanwhile, has turned over board and management and is stalked by former Coles Myer executive chairman Solomon Lew as it tries to find a winning formula.

7. Japan Post’s purchase of Toll Holdings, 2015

Toll Holdings shareholders could hardly believe their luck when Japan Post came knocking with a bumper $6.5 billion offer for the company in 2015. A 49 per cent premium for a company that analysts believed was not doing well seemed almost too good to be true, and so it turned out. Just two years later, Japan Post would write off $4.9 billion – 74 per cent of the purchase price.

In a reminder of the consequences of overpaying, new management at Japan Post would order changes at Toll that saw divisions rationalised and 1700 jobs cut. A buyer eager for a growth kicker ahead of its own $12 billion float apologised for its hasty acquisition and for failing to do its research.

It was the last big payday for founder Paul Little, who had left the group in 2011 but collected $338 million on his shares. He had previously got the better end of a deal to split Toll’s port and rail assets into a new debt-heavy company, Asciano, headed by his business partner, Mark Rowsthorn. After he left, new management led by John Mullen turned that business around before a $10 billion takeover spearheaded by Little’s old adversary, Chris Corrigan. As executive chairman, Mullen is leading the turnaround at Toll.

8. Woolworths and Wesfarmers hardware expansion

Wesfarmers had a halo from the runaway success of its Bunnings hardware business and had “earned” the right to move offshore when it bought the UK’s Homebase business for $705 million in 2016. Surely they couldn’t stuff it up.

In an extraordinary coincidence, the deal was announced the same morning that Woolworths unveiled plans to extract itself from the Masters hardware joint venture with US retailer Lowe’s. That had cost $2.3 billion to build and lost $600 million. Fast forward two years and new Wesfarmers chief executive Rob Scott unveiled $1 billion in writedowns on Homebase after hamfisted attempts to make it a Bunnings UK. It’s been sold for £1.

At Woolworths, the Masters losses contributed to CEO Grant O’Brien being replaced. He conceived the venture to put pressure on Wesfarmers at a time when management was precoccupied with the turnaround of Coles, but allowed Woolies’ sales growth to drift so badly that it was trounced by Coles for years. Now Wesfarmers is spinning off the Coles supermarkets business because its returns are too low for the conglomerate.

9. AMP’s $14.6 billion stake in AXA, 2011

Under the old six pillars policy, AXA – the former National Mutual – was off limits to its Sydney-based rival AMP. There’s an argument it might have been better if things had stayed that way, rather than allowing AMP to get into a bidding contest with NAB.

The early-2011 deal for AMP and AXA’s French majority shareholder to carve up the business in a $14.6 billion cash and scrip deal has not delivered the hoped-for riches, or lifted AMP out of a decades-long decline. The France-based AXA took the most attractive growth assets in Asia, while AMP doubled down on the life business just as it was entering a period of escalating claims and slimming profits. AMP shares used as currency in the bid were worth $5.60 then and are now just above $3; its present market capitalisation of $9 billion is $2 billion less than it was before the deal was announced – and that’s after issuing all of those shares.

Profits of $812 million in the year before the deal rose to $869 million in 2017. Revenue has grown strongly, and the company continues to praise the North wealth management platform that was a key part of the deal. But it was a high price to pay.

10. BrisConnections float, 2008

In polite terms, toll roads have ended up as good investments for their next owners.

BrisConnections, however, might have been the worst of a bad bunch of private sector financings that featured overly optimistic traffic forecasts, outsized fees and big investor losses. Built for $4.8 billion, the 6.7km toll road connecting Brisbane Airport to the CBD was sold out of receivership to Transurban for $2 billion in 2015.

The project was in trouble from the start. The float launched in early August 2008, just a month before the collapse of Lehman Brothers ushered in the darkest phase of the global financial crisis. Its $1 partly paid shares crashed in value by 60 per cent on the first day of trading, on their way to a low of 1c. A young punk from Melbourne, Nicholas Bolton (above), snapped up 20 per cent of the company for $50,000 and took it to the brink of a vote on liquidation in 2009. It later emerged that he had sold his voting rights to tunnel-builder Leighton and walked away with $45 million. Traffic was forecast to hit 170,000 cars a day but had reached just 50,000 when Transurban took over.