Provenance now the catchcry for wool industry

First it was food and wine, now the world wants to know that our fleece has a provenance to cherish.

Peter Vandeleur is searching for a rock-star farmer. “Right now I’m talking to one who might supply to a major clothing brand,” says the managing director of NewMerino. “I have a long list of about 100 points on what I call my farm profile, and he’s passed. Whether he has clean fingernails I’m not sure.”

Clean fingernails are probably the only things a rock star farmer doesn’t have to worry about when the fashion photographer rolls up to the farm. By the time he has been selected as the face of the fabric, he would have accumulated a showreel of skills ranging from sheep husbandry and land stewardship to how he flashes that all-Australian smile shaded by a hard-worn hat.

The appearance of Vandeleur and his checklist on the rural landscape marks a radical turnaround in one of Australia’s oldest industries. Wool is changing from a bulk commodity that loses its identity as soon as it leaves the farmgate into a branded fibre that brings global fashion labels into the woolshed and, indeed, the wool farmer’s life.

Provenance is the catchcry across Australian agriculture. According to a CSIRO report on agribusiness last year, Australia ranks 16th out of 80 countries for green values; the number of global consumers prepared to pay more for sustainable brands has jumped from 50 to 66 per cent; and for the first time ever, exports of value-added food accounted for the majority of food export growth.

Australia has capitalised on adding value to food that won’t kill you and wine that comes from where it says it does. But the interest in sustainable fibres has taken some by surprise. Surely wool is just the thick and scratchy sort or the fine and smooth stuff?

“A lot of this started with food security but it’s gone beyond that because a lot of consumers are now label turners – they like to turn the tag around and look for provenance,” says John Roberts, chief of Australian Wool Innovation. “That’s great for wool because it’s natural, sustainable, biodegradable and long lasting – all the things fast fashion isn’t.”

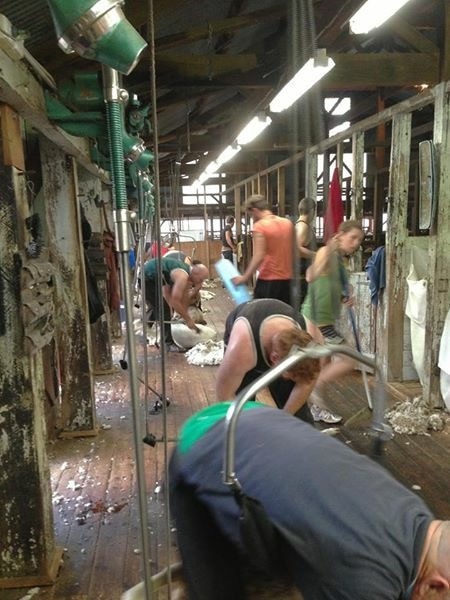

Roberts says wool representative bodies are accustomed to taking wool manufacturers around Australian farms, but more recently, “it’s the fashion brands that wander around the paddock, have a go at shearing and generally get romanced by it all”.

Some of the big names that have visited paddocks include Burberry, Max Mara, Prada, Comme Moi from China, and Muji and Facetasm from Japan. If you visit their online catalogues, the Australian bush backgrounds many products.

But the big growth will come from sports brands and brands that want to use functional fibres. Says Roberts, “Sports brands are discovering that wool is breathable, water-resistant, has elasticity and wicking abilities and odour management, so finally that old-world image of scratchy woollen jumpers is shifting and people are discovering how good next-to-skin wools are.”

This is a sweet spot for Australian wool. As world consumers react against fast fashion and opt for what Prince Charles has described as “conscious clothing”, wool is the go-to fibre. And not just for rich Westerners. China has taken a liking to our wool. In the last year, wool exports rose 9 per cent solely because of a 17 per cent leap in exports to China. What’s more, the value of fine and superfine wool exports jumped 23 per cent, and even medium wool (20 to 23 microns) leapt 62 per cent. If sports apparel and leisurewear join the rush for wool, this will dwarf the sales to high-end fashion brands.

All this is happening at a time when the national flock is down to 70 million (from 180 million in 1970), leaving only the most resilient and innovative farmers in the game. And the final sweetener is that Australia has a virtual monopoly, supplying 90 per cent of the world’s wool for the apparel market.

But the shift from bulk commodity to brand comes at a price, and that price is on Peter Vandeleur’s checklist.

“Originally the big spinners came to me to address issues of quality but it has broadened out to include animal welfare issues and more recently, environmental and land use issues,” he says.

“Until recently, no one knew where wool was grown, how it was grown and who grew it. Wool lost its identity once it left the farm, but now brands have to be assured that their brand isn’t damaged by a bad story coming out of the people who supply the raw materials. Everyone remembers the Nike sweatshop story.”

This is literally changing the way Australians farm. One of those who is working towards becoming a rock-star farmer is Clare Cannon. Six years ago, the former environmental activist took over the historic Woomargama Station in NSW from her parents, Gordon and Margaret Darling, and she is working towards becoming a single origin supplier to a big brand.

“When I took over everyone was saying get out of wool, it’s all over, and I thought, great, I’m glad they’re getting out because I’m staying in,” says Cannon. “In my first year I went to the wool auctions and started chatting to a European wool buyer and my ears pricked up, because he was interested in all those sustainability issues and animal welfare issues.”

Following the philosophy “you do what’s right, not what’s easy”, Cannon changed the way her sheep are transported and installed pens into the woolshed for monitoring, but the biggest change was her decision to place a third of the property under a conservation covenant.

By isolating a portion of her property for conservation, Cannon says that she’s not just doing the right thing by the land but “sending a message that we’re interested in doing the right thing. Farmers generally get a bad rap with things like methane emissions, animal handling, use of antibiotics, and we want to change that.

“Also, there’s a growing awareness that fashion is shocking for the environment, with some cotton farming practices, water uses and the whole industry around fast fashion, and consumers are switching off that.

“People are also realising that wool isn’t a generic product. The state of wool is related to climate, weather, the diet and treatment of sheep, and even the transport of them.”

Having grown up surrounded by the cockie culture, Cannon now sees a new generation of farmers around her.

“Food is the new rock and roll and farming is part of that,” she says. “There are a lot of young women doing bespoke things and lots of young farmers doing different things with breeding and growing, so that old cockie influence is disappearing. When I started, everyone said, if you want to be a greenie you’re not going to be profitable. Now I think if you’re not a greenie it’s getting hard to be profitable.”

Cannon sells her wool under the SustainaWOOL label at auction and says that usually gets a premium price, but more broadly, the profitability of becoming a branded producer is still questionable. Sure, there is a widening premium for fine and superfine wool; there is also a premium for wool from farmers who don’t do mulesing – between 50 cents and $3 a kilo. But new methods of marketing wool may widen the gap.

At present 90 per cent of the wool clip goes through the auction system, leaving only 10 to 12 per cent of the product that’s either sold direct to the brand or mill in a partnership agreement, or goes through the new broker networks that are being setting up.

One of those networks, Merino & Co, has just launched an online store of wool products to connect its 8000 wool growers in the network with the brands. Chief marketing officer Cynthia Jarratt says the key to closing the circle of farmer to consumer was the introduction of an electronic swing-tag a consumer can click on with their smartphone to view videos of some of the farmers responsible for the fibre. Cue craggy smiles and hard-worn hats.

“Sharing those stories with the consumer is key to providing provenance,” says Jarratt, “and while it’s still niche, there’s increasing interest from large labels that want to build their connection with the origins of the wool they use.”

The other method that manufacturers use to secure single origin wool is to buy stations.

Several years ago, the Sudwolle Group bought the historic Mt Hesse property, and more recently the Ermenegildo Zegna group bought the Achill Farm near Armidale.

John Roberts says we will see more partnerships between growers and brands “because the price at auction might not reflect the value of that wool to a brand that prioritises provenance and stories. And more younger wool growers are savvy about how they sell their wool. They want to become more invested in the process rather than wave goodbye to it at the farm gate.”

As an independent verifier of the supply chain, Peter Vandeleur is blunt when predicting how the evolution of wool farming will progress.

“There are two camps at the moment: those farmers who have ceased mulesing and want to be recognised for it and those who haven’t stopped mulesing and don’t want to know about it,” he says.

“Until recently, there hasn’t been much of a price difference, but then wool prices are at the highest levels ever so brands are getting resistant to high prices and tend to say you don’t have to get rewarded just because you’ve stopped beating your wife, so to say.

“But the price difference will increase and eventually those farmers who don’t change their ways will be disadvantaged. The prices they get will be discounted and eventually they might not be able to sell their wool.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout