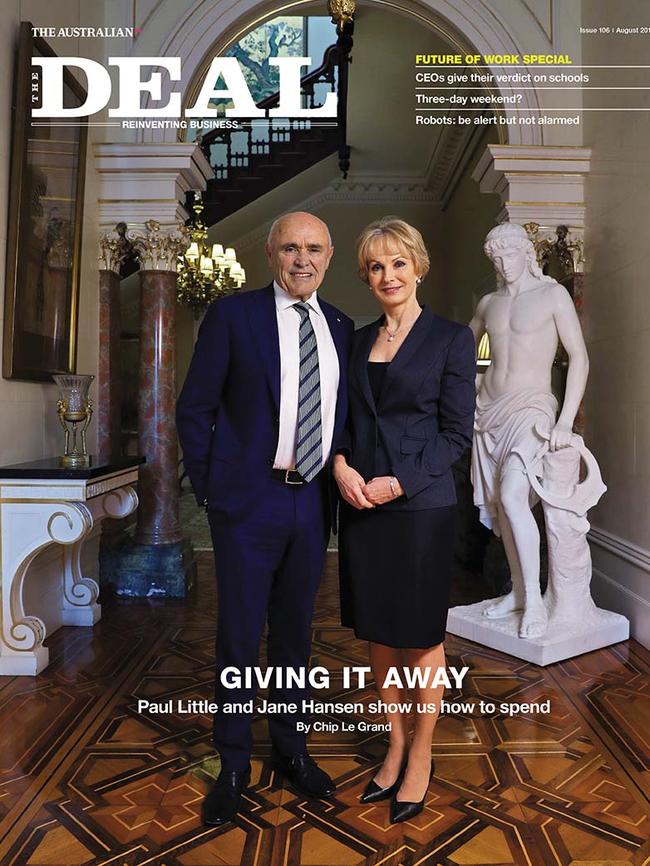

Giving it away: Paul Little and Jane Hansen and the Hansen Little Foundation

The most fascinating, high-achieving husband and wife team in Australian business show us how to spend.

It might be a scene lifted from the pages of a Tom Wolfe novel. Jane Hansen, a rising star within First Boston, a big mergers and acquisitions firm stalking Wall Street, is driving through the backstreets of Brooklyn, a slow panic rising as she navigates the foreign landscape. Only it isn’t Brooklyn, New York. She’s in a western suburb of Melbourne where, on a hot day, the nor’wester gathers up the stench from the local tip and blows it through cracked and dusty streets, where B-double trucks laden with containers rumble to and from the port in a wheeze of diesel fumes and airbrakes.

She’s there, she thinks, to ease her own load for a while.

For five years, Hansen worked at a frenetic Manhattan tempo for a global investment banking firm, helping to stitch together some of the biggest deals in corporate America. On returning to Melbourne, she was pitched into one of the great Collins Street battles – John Elliott’s existential struggle against Robert Holmes à Court and his own debt-saddled company, Harlin Holdings.

It’s been exhilarating and exhausting. Now, in an abrupt change of pace, she’s been asked to help a small Melbourne trucking group organise an initial public offering.

“They said: go over and do this little IPO,’’ she tells The Deal. “Go to Brooklyn and find this guy and take his company public. I never knew there was a Brooklyn in Melbourne. Over the Westgate Bridge, cyclone fencing, potholes and trucks everywhere. I think, where am I going?’’

Her drive takes her to the end of a narrow industrial street that runs behind a rail line shunting freight trains from the docks. She walks up a steep set of stairs and finds an unimposing man, standing in shirtsleeves, looking across the truck yard. This is her client.

“I’d come from an era of beautiful suits, braces, matching kerchief – the whole Gekko thing,’’ she says. “This guy has got no tie on. It’s thrown on the desk and I notice it’s polyester.

“That was Paul.’’

Paul Little, self-made billionaire and one half of Hansen-Little, an emerging power couple of Australian philanthropy, laughs at the imagery and his wife’s uncanny memory for detail. “I probably didn’t know the difference between polyester and silk in those days,’’ he says.

The story of how Little turned that trucking company into a global logistics leviathan is the stuff of Australian corporate legend. From the time of its public listing, Toll gobbled up 120 companies, here and throughout the Asia Pacific region, in a ravenous expansion. The main course was the acquisition of Patrick Corp – and the vanquishing of Little’s corporate nemesis Chris Corrigan – after a protracted, bitterly resisted takeover. In 2015 Toll was sold to Japan Post, and Little, having run the company for 26 years, exited a very wealthy man. Forbes magazine this year estimated his personal wealth at an even $1 billion.

‘He was a widower keen to remarry. She wasn’t so sure.’

The part Hansen played in all this is less well known.

A stockbroker and corporate adviser who’d worked in London, studied at Columbia University and cracked into uber-macho Wall Street at the height of the 1980s madness, she had no inkling that she’d met her life partner that day in Brooklyn. As she explains, it was well after she’d finished her work on the Toll listing that their personal relationship began. He was a widower keen to remarry. She wasn’t so sure.

“I had no intention of getting married, ever,’’ she says. “The main thing that swung the deal is he is decent and trustworthy. He is just a very decent, solid guy.’’

It is a formidable partnership. Little has a rare talent for spotting and seizing a business opportunity. Hansen has an investment banker’s rigour and eye for detail. Together, they share a love of the deal. It’s what drove Hansen into the cut-throat environment of mergers and acquisitions; it’s what most excited Little when Toll was a company on the rise. Hansen didn’t have a formal role within Toll but when a deal was in the offing she would scour the documents, identify gaps in the analysis and make sure Little had the best people advising him.

“It is probably unusual to have a husband and wife working on these things but our skill sets really do complement each other,” Little says. “She is fiercely smart around finances and people. She has also got a genuine desire to be a person in the community who helps and understands and contributes.”

Together the pair are the driving force behind the Hansen-Little Foundation, one of Australia’s most substantial private ancillary funds.

The HLF, which Hansen chairs and Little serves as a director, was established in 2015 and has already shaped the future of some of Melbourne’s most important institutions: the University of Melbourne, the State Library of Victoria and the Melbourne Theatre Company.

Earlier this year the foundation made its largest donation: a $30 million gift to the University of Melbourne to build a student hall of residence and establish a scholarship program for those who would otherwise not have the opportunity and means to enrol at a sandstone university.

Little Hall, an apartment building that will accommodate 669 students, will cost about $100 million to build. The HLF is contributing the first $30 million and the university the rest. The building will be owned by the university and the rent it collects will provide a new source of revenue, part of which will fund the Hansen Scholarship program.

Starting in 2020, the scholarship program will meet the cost of tuition and living expenses, and provide additional tutoring, mentoring and pastoral care, for 20 Hansen Scholars, who will all reside rent free for three years at Little Hall.

At the end of their undergraduate degree, each scholarship holder will be invited to present to an academic board to request a further grant to support their careers. The university has committed to funding the program for 40 years.

‘Hansen insists that there is nothing remarkable about two wealthy people giving back some of their money.’

The design of the project seems a natural fit for Little. Since leaving Toll, he has channelled his business energies into building the Little Group of companies, the most visible of which is Little Real Estate, a fast-growing property management and sales company. It is also something close to the heart of Hansen, who still recalls the dismissive advice she received from her high school career counsellor when she revealed her ambition to go to university.

“With this scholarship, it is finding young people who have that X factor,” she says. “I want to find kids who would not have otherwise dreamed. If I get the students I want they are not going to have the social capital that you or I have. They are not going to have people hold doors open for them in Collins Street, they are not going to have parents who can pay for them to do a conservation internship.

“It is tough for young people out there. I’m keen to retain some of the funding to provide postgraduate opportunities so these students have a more level playing field in whatever field they choose.”

Hansen insists that there is nothing remarkable about two wealthy people giving back some of their money.

“For me, the value of money is in providing opportunity for others,” she says.

What is unique is the scale and nature of the gift. Leading universities more commonly receive donations for research or to offer courses in a particular area. University of Melbourne vice-chancellor Glyn Davis says the HLF gift is the largest ever made for the direct benefit of students.

“No one really helped Jane and I in our careers,”’ Little says. “Whether that is a motivation for us, I’m not sure, but we know how hard it is and we want to enable young Australians to have the best start in life possible.

“I think what we are doing is terribly exciting and will uncover some very special kids. We are not just building them a nice apartment building; there is a more going on. It is ambitious but I think it may be a model that other universities look at and consider.”’

For Little, charity began at work. His first philanthropic cause was a drug rehabilitation centre in the red light district of St Kilda called First Step. It was 20 years ago, before the Ice age, when Melbourne was flooded with cheap amphetamines. Drugs were a problem in many industries and a particular problem in long-haul trucking.

Little wanted to know the size of any potential problem at Toll. He also wanted to develop a pathway for drug addicts, once they were clean, to rebuild their lives.

“At the completion of the First Step detoxing program, there was concern that individuals may be tempted to re-use drugs,” he says. “There was a clear need for greater intervention through the creation of gainful employment and providing a new start.’”

Toll called the program Second Step.

“I used to go to Port Philip Prison and talk to the inmates. I would talk to them about how we could train them to a point inside prison so that when they got out they could hit the ground running, start earning an income and rebuild their self-esteem.

“I met this one kid who was around the same age as my son. He’d been out with his mates, they’d got on the grog and he was the least affected so he said ‘I’ll drive.’ He hit someone and killed them and went to jail for eight years. I spent time talking to him and it made me realise that any one of us could so easily end up in that situation.

“I’ll never forget the AGM where I decided to tell the shareholders about the program. I felt they needed to know we were employing people who were not only coming out of drug rehabilitation, but quite often jail. I spent a fair bit of time telling the assembled shareholders what we were doing. We got a standing ovation. That blew me away.”

Little credits Ruth Oakden, a long-serving company chaplain with Toll, with creating Second Step, a program that has resulted in about 500 people moving from drug addiction and jail into permanent employment. One of his few regrets is that he couldn’t convince other ASX 200 companies to introduce a similar scheme. “It is a massive disappointment,”’ he says. “People aren’t willing in business life, in corporate life, even in government, to try to manage that risk. We saw an opportunity for people to become amazing employees, and invariably they did.”

For Hansen, philanthropy was a natural extension of the choice she made at the end of her corporate career to devote her time and expertise to not-for-profit organisations such as the MCG Trust, Athletics Australia and the State Library of Victoria Foundation. She is on the board of the Melbourne Theatre Company and chairs the MTC Foundation, established two years ago with HLF seed money. At the University of Melbourne, she is deputy chancellor, on the board of the Melbourne Humanities Foundation, and a mature age student in the final year of an Arts degree.

It was during Hansen’s first year back at uni, when she enrolled in a history course, that she saw the parlous state of the department and the difficulties academics faced in meeting the needs of students. Her first significant donation was a $10 million grant to the university’s Arts Faculty, $8 million of which was earmarked to reform the history curriculum and improve the way it was taught.

Since then, the History Department has expanded from 14 to 19 academic staff and through the work of the Melbourne Humanities Foundation, five new professorial chairs have been created in the Arts Faculty.

Hansen describes giving as the best feeling in the world.

“Who cares about another handbag,” she exclaims. “Seriously, what am I missing here?”’

When asked whether it is more fun making money or giving it back, Little pauses. “Some of the more public deals were really challenging but hugely rewarding. Putting together a unique solution to help solve a community problem or improve the lives of many is even more exciting, as it makes the whole journey worthwhile. It’s the ultimate purpose.”

The building of Toll

1986

Toll managing director Paul Little and company chairman Peter Rowsthorn buy a century-old transport company that began as a family-run carting business in Newcastle.

1993

Advised by Jane Hansen of the New York-based First Boston investment bank, Little lists

Toll on the Australian Stock Exchange. The company embarks on a sustained expansion strategy here and throughout Asia.

2006

Little completes the toughest takeover of his career, buying out rival Patrick Corp and turning Toll into one of the Asia Pacific’s biggest logistics companies.

2015

Toll is sold to Japan Post for $6.5 billion and Little retires as company chief executive, cashing in a personal stake of $338 million.

Life after Toll

Since leaving Toll, Paul Little has grown Little Real Estate into Australia’s largest privately owned real estate agency, with 23 branches, 400 staff and 25,000 properties under management. The Little Group, which Paul Little founded and chairs, also includes Little Aviation, a corporate and private jet charter based at Melbourne Airport; Port Phillip Ferries, a ferry passenger service between Melbourne and Geelong; and Little Projects, a developer of

high- and low-rise buildings for residential and student accommodation.

The Hansen Little Foundation

2015

Jane Hansen and Paul Little establish the Hansen sLittle Foundation, a private ancillary fund with Jane Hansen as chair and chief executive.

The foudation’s first major donation is a $10 million gift to Arts and Humanities at the University of Melbourne.

2016

The HLF provides $1 million to establish the Melbourne Theatre Company Foundation, the company’s largest source of revenue beyond box office sales.

2017

The HLF contributes a $3.5 million gift towards the redevelopment of the State Library of Victoria.

2018

The foundation provides $30 million to the University of Melbourne to build Little Hall, a $100 million student residence, and establish a 40-year scholarship program.