Even Steve Jobs had an ‘outsider’ on the inside to kick off his business

Outsiders might struggle to get traction but they are not outliers and are important for your business.

Every once in a while, an outsider comes along with a new vision or a new way of doing things that revolutionises a scientific field, an industry or a culture.

Take the case of Katalin Karikó (below) who defied all odds to pioneer the mRNA technology that ultimately gave the world a group of Covid-19 vaccines in record time. A daughter of a butcher, raised in a small adobe house in Europe’s former Eastern bloc with no running water or refrigerator, Karikó started working with RNA as a student in Hungary but moved to the United States in her late twenties.

For decades, she faced rejection after rejection, along with the scorn of colleagues, and even the threat of deportation. Yet today, Karikó’s foundational work on mRNA is at the heart of the vaccines developed by BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna, and a number of researchers are now calling for Karikó to be awarded the Nobel prize.

How did that happen? After 10 years of research, relying on a mix of qualitative techniques, large data set analyses, and historical research we have come up with four factors that can contribute to the success of outsiders like Karikó. These factors do not have to be concomitant, and none is necessary, but each substantially increases the odds that an outsider will break through and that their innovation will have a major impact.

OUTSIDERS ARE NOT OUTLIERS

Our research suggests that successes like Karikó’s occur not just despite outsider status but because of it. Being less tied to norms and standards to which insiders conform, outsiders recognise solutions that might escape incumbents’ attention. Yet, the paradox is that the same social position that gives outsiders the perspective to pursue imaginative projects also constrains their ability to obtain support and recognition for their innovations. How do the innovations of outsiders like Karikó gain traction?

The innovation pattern we observed in our research is very consistent. Outsiders typically innovate by acting on insights and experiences that are new to the environment they have entered but familiar in the context of where they came from.

Consider Coco Chanel (below), the illegitimate daughter of a laundress and a street peddler. Abandoned and raised by nuns in an orphanage, she found there original inspiration for some of her most iconic design concepts.

For example, her legendary predilection for black and white is generally attributed to her prolonged exposure to the colours of the orphanage uniforms and the nuns’ tunics. Even the distinctive Chanel logo was an idea she gleaned from a simple stained-glass window in the orphanage, the Abbey of Aubazine.

You would think that successful outsiders like Karikó and Chanel are statistical outliers, but we find that this is not actually the case. In one of our studies, we analysed the network of collaborations of approximately 12,000 Hollywood professionals to explore whether creative success is concentrated at the centre of the system or at its margins. What we found surprised us: the most successful artists were not those at the extreme periphery of the network, but neither were they “network kings” at the heart of their industry. The outsiders were not outliers. This study showed that the probability of creative success was highest in a border zone between the centre and the periphery, by artists who belong to the system but have not lost touch with its fringes.

BEHIND EVERY STEVE JOBS IS A MIKE MARKKULA, A CHAMPION ON THE INSIDE

Thinking like an outsider can have advantages, but practising the way of the outsider is complicated. Outsiders are strangers. They do not hold élite positions, and they have limited resources and lack the credentials of better-connected people whose theories or practices they are challenging. Not surprisingly, they often stay locked outside.

Our research suggests that the outsider needs at least one insider who is willing to vouch for their ideas or abilities. In collaboration with Paul Allison, a sociology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, we went back to our Hollywood network and gathered new data on thousands of awards bestowed by two crucial audiences in this industry: critics and peers. Our statistical analyses revealed that critics were more likely to praise peripheral artists than insiders. Conversely, industry peers are more likely to favour their fellow insiders. From the outsider’s perspective, this means that one effective strategy to gain traction is to identify an audience – a person or a group of people – that has a cognitive or emotional affinity for the outsider or their ideas (as well as the credibility that the outsider usually lacks).

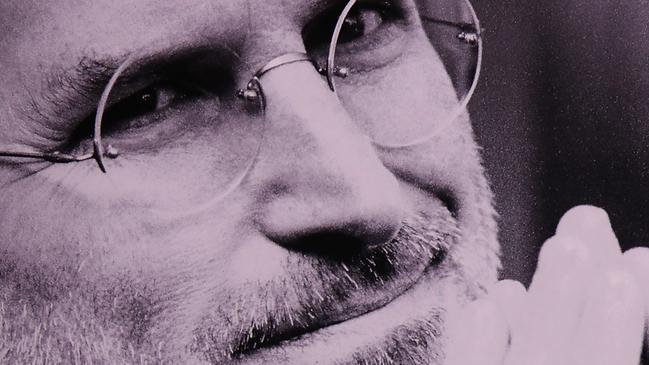

Steve Jobs’s early career is a case in point. The VC industry repeatedly refused to support his project, but Jobs (left) kept searching for a receptive audience. Finally, he met Mike Markkula, a wealthy young engineer who saw potential where the VC establishment saw only roadblocks. He made the first investment in Apple Computer.

‘FRACTURE POINTS’ LET OUTSIDERS IN

A third way outsiders break in is by leveraging what we call “fracture points” – events that generate intense stress on the system. One particular class of fracture points that we have been investigating reflects Max Planck’s famous quip that “an important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: it rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul. What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out.” The idea is simple: when the gatekeepers die, they create space for the entrance of the new.

DISRUPTION IS A MARKETING CHALLENGE THAT CAN BE OVERCOME

After being rejected by every major journal, Karikó’s breakthrough research was finally published in 2005. For years, however, it still got little attention. “We talked to pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists. No one cared,” her research partner, Drew Weissman, recalled.

Most established organisations and industries tend to reproduce the power and privilege structure of incumbent groups, reducing outsiders’ chances of making their ideas heard and proving their worth. But our research suggests that outsiders should not be daunted: the very traits that make outsiders so disadvantaged within established occupational structures and professional categories are often precisely those required for the pursuit of exceptional entrepreneurial achievements in art, science, and business.

Often, extraordinary outsiders’ primary problem is not their ideas but selling those ideas, precisely because of their disruptive implications. As the late Clayton Christensen noted in his 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, “disruptive technology should be framed as a marketing challenge, not a technological one”.

Gino Cattani is a professor of strategy and organisation theory at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business. Simone Ferriani is a professor of entrepreneurship and innovation at the University of Bologna and City University of London

Copyright 2020 Harvard Business Review/Distributed by the New York Times Syndicate