Diverse voices

Indigenous literature is an unfolding narrative.

Alexis Wright, Kim Scott, Melissa Lucashenko, Tony Birch and Ellen van Neervan are some of the award-winning writers leading a burgeoning indigenous literary movement in this country. They are original and sophisticated, and their writing enlarges our understanding of what it means to be Australian in the 21st century: they are contemporary storytellers who owe much to a long tradition.

Since the emergence of indigenous Australian literature in English in the 1960s and 1970s, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers have challenged Australian complacency, rewritten history, and demanded recognition of their cultures and identities.

Writing in English and employing Western cultural forms has been controversial: the English language plays an ambivalent role in the work of these writers, signifying the loss of their languages and colonial control. It is too simplistic, though, to see writing in English as false or inauthentic, as some critics have done. Many of the most celebrated of these writers have made English their own; indeed, in their hands, it has become a tool of resistance and inspiration, stretching the language beyond its usual limits. Put simply, they have found new ways to tell the stories they need to tell, and the stories we need to hear.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a boom in Aboriginal life writing. While Sally Morgan’s My Place (1986) is often seen as the watershed for such narratives, increasing numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders began writing their own stories of loss and survival focused on the personal, the familial and the community. Ruth Hegarty’s 1999 memoir, Is that You, Ruthie?, Jackie and Rita Huggins’s 1994 collaborative memoir Aunty Rita, Wayne King’s ground-breaking autobiography Black Hours (1996), and Doris Pilkington’s Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence (1993) all call for empathy and respect. But they also serve as “testimony” of the past, challenging us to remember it in the face of denial and forgetting. These writers insist on the truth of their stories.

The focus on the “authority of experience” saw a spurious notion of “authenticity” become a key criterion by which indigenous writing was judged, a situation that intensified in the late 1990s as a number of high-profile “indigenous” writers were outed as non-indigenous. But a focus on authenticity can blind us to the history of racism and assimilation in Australia that makes such authenticity not only philosophically problematic but also historically impossible.

Contemporary indigenous writing deserves more thoughtful consideration. These writers move across genres and literary forms and produce literature that enriches and unsettles the landscape of Australian writing. Their writing is characterised by a radical rethinking of identity politics, and complicates simplistic notions of a homogeneous Aboriginal identity. They challenge complacent understandings of indigenous community, revealing tensions between the rural, the urban and the suburban, and exploring the causes and effects of unequal power relations within and outside indigenous communities. They can also be hopeful and loving. And one constant has been the abiding concern of so much of this literature with connection to country.

Kim Scott, a Noongar from the south-west of Western Australia, has twice won Australia’s most prestigious literary prize, the Miles Franklin Award. The first was for Benang (2001), a scathing indictment of Western Australia’s genocidal assimilation policies and their contemporary consequences; the second was That Deadman Dance (2010), a melancholic story of cross-cultural confusion on the “friendly frontier” that wonders what might have been if the settlers had been more open to cultural exchange, and less greedy.

Alexis Wright, a Waanji woman from the Gulf of Carpentaria, is one of Australia’s most sophisticated and original writers. Her multi-prize-winning novels include Plains of Promise, (1997), Carpentaria (2006), which also won the Miles Franklin, and The Swan Book (2013). Her writing has an urgent and epic quality and reveals the devastating legacies of colonialism, the fragmentation and despair caused by dispossession and state intervention, and the environmental destruction caused by industrialisation and lack of care for and knowledge of country.

Tony Birch, the Melbourne-based writer and historian, is also concerned with environmental destruction but his writing is quite different, with its stark realist narratives of lives of poverty in urban Melbourne and its taut language. Underlying his work is a repressed violence but also a heartfelt kindness that makes his writing both gripping and disturbing.

Melissa Lucashenko, of Bundjalung, Yuganmeh and European descent, is a major talent in Australian young adult fiction. Her novels share a concern with the complexity of identities that go beyond race to include gender, class, sexuality, age, embodiment and spatial location. All of these categories are situated by Lucashenko in ongoing processes of colonisation and dispossession.

Some of these writers use comedy to tell their stories; Marie Munkara’s Every Secret Thing (2009), and Vivien Cleven’s Bitin’ Back (2001), are standout examples of the way comedy can jar and seduce. And Anita Heiss leads a whole new genre, “Indigenous Chick-lit” – serious politics mixed with the loves, lives and shopping of young urban women.

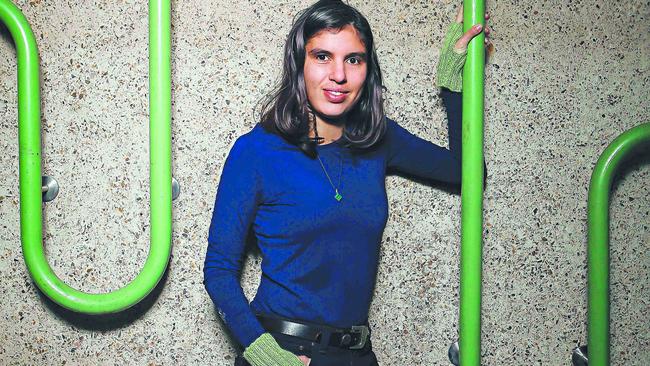

Now a new generation of writers is emerging: the young Queenslander Ellen van Neervan’s most recent short story collection, Heat and Light (2014), offers three interconnected stories of vivid depth and subtle richness. She will be one to watch in the years ahead.

Indigenous literature ultimately has the power to reshape and unsettle what it means to be Australian in profoundly discomforting but ultimately productive ways. Indeed, the label “Indigenous Literature” can hardly account for the sheer range and diversity of contemporary indigenous writing in Australia, its multiple concerns, its global relevance and its generosity.

Dr Maggie Nolan is deputy head (Qld) of the National School of Arts at the Australian Catholic University.