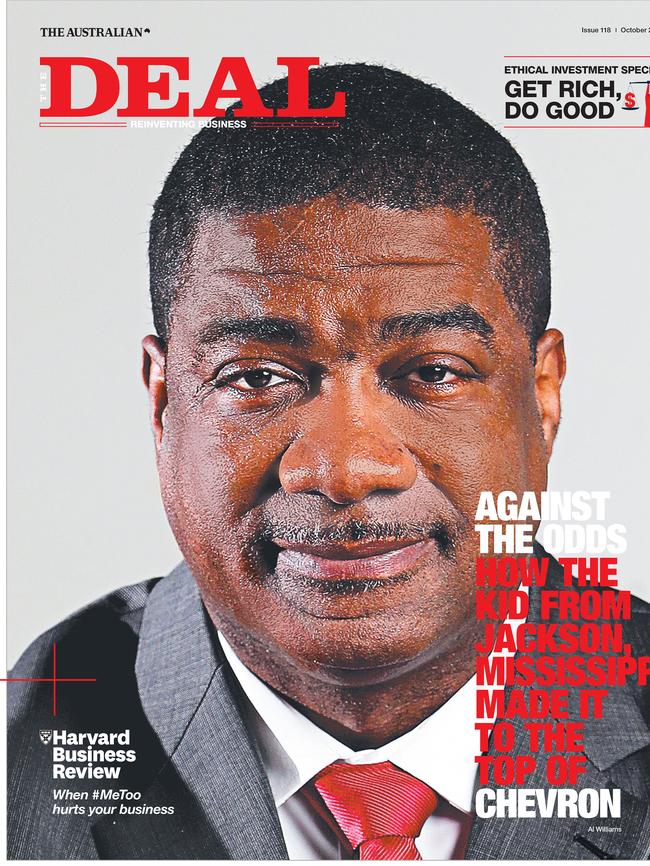

Chevron boss Al Williams lives the American dream

The demographics were against Al Williams, but now the Chevron boss lives the American dream.

Al Williams’ journey from a poor, inner-city neighbourhood in Jackson, Mississippi to a role running some of the biggest industrial assets in Australia is defined by a series of moments which, if they had played out differently, could well have sent him down a different path.

Williams, who earlier this year started as the managing director of Chevron Australia, was the second youngest of 11 children in the Williams family. His mother Essie gave birth across four different decades, with the eldest born in 1949 and the youngest in 1970.

The demographics were against Williams and his siblings from a large, black family from an impoverished part of America. Neither his mother nor father completed high school. His mother had lost that opportunity at just 13, when her own mother died. As the eldest child, she was forced to drop out of school to care for her siblings.

Despite the limited formal schooling of their parents, there was an intense focus on education in the household. It endured even after the parents divorced when Al (full name Albert) was three. The Williams children were aware from a young age that their mother had missed out and her history drove their belief in education. Of the 11 children, eight would go on to earn university degrees, with three Masters and one PhD among them.

“Early on, our mum instilled in us from her own situation the importance of education,” Williams tells The Deal in his first interview since arriving in Australia. “It wasn’t because she wasn’t interested in doing it, it was because the situation didn’t afford her the opportunity. One of the things that drove her was making sure she afforded to us the opportunity that she wasn’t afforded herself. That in itself is probably what motivated all the kids because, as you came to understand her situation, you gained an appreciation for how lucky we were, that we were going to be afforded that opportunity.

“Growing up in a poor inner-city neighbourhood, we were still part of that American Dream that through education, you can do great things and you can be who you want to be. We believed in that and we pursued it.”

Today, Williams is at the top of his game, responsible for some of the biggest assets within one of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies. After an entire career with Chevron, he finds himself in Perth as the public face of one of the biggest energy companies in Australia at a time when the sector is under pressure on several fronts — from governments, regulators, the public, and even its industry peers.

Chevron’s two flagship Australian projects, the Gorgon and Wheatstone LNG plants, cost a combined $US88 billion to build and each ranks among the biggest industrial projects in Australia. Williams oversees it all from an office overlooking Perth’s Swan River. He also has a bird’s eye view over Elizabeth Quay, the riverfront site where Chevron is building its new headquarters.

‘Early on, our mum instilled in us the importance of education’

It is a world away, literally and figuratively, from Jackson where typically four Williams children shared each bedroom and where their mother spent 40 years working as a cleaner to support the family. The Chevron boss recalls that from the age of eight, he woke with his mother at 4.30am to help her clean offices before school.

Sibling rivalries spurred competition but the historic events of the US civil rights movement in the 1960s fuelled Williams’ ambitions. It was in Jackson in 1960 that 300 “freedom riders” arrived by bus and were swiftly arrested. Three years later, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his Jackson home by a white supremacist.

By the time Williams started his education, the desegregation of Mississippi’s schools had begun and unlike his older siblings he knew from an early age that he would be offered opportunities denied an earlier generation.

“Six of those [who finished university] did that during that period when there was segregation, when they weren’t being afforded as many opportunities as I was,” he says. “In spite of those barriers and challenges, they were still able to find a way to realise their potential and pursue their aspirations. My expectation of me was that I should be able to do what they did, and more importantly I should be able to do more, because I didn’t have to expend as much energy just trying to open doors.”

At the age of five he and his younger brother were sent to Washington DC to live with their eldest brother Fredie and his wife Verline. Their mother was struggling to cope financially as a single parent and the little boys were taken in by the couple, stationed in the capital with the military. Beyond the practical relief for his mother, that year in DC left an indelible mark on Williams, opening his eyes to the world beyond Jackson.

“It would be questionable whether I’d be here today and in the role I am in today,” he says. “Instead of getting lost as just another kid on the street, I had the chance to get placed in a structured environment and as a young kid got to actually see what was possible.”

Some 35 years later Williams returned to Washington in very different circumstances. Travelling with him were his mother, then 77, and his then four-year-old daughter. The occasion was the 2008 presidential inauguration of Barack Obama. The chance to take his mother — a black woman born during the Great Depression, who had spent the first half of her life under segregation — to see the inauguration of the first black American president was a “monumental” moment.

“It put all of her own struggles into context and reinforced that we can achieve greatness if we are afforded the opportunity and we apply ourselves,” Williams says. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that I wanted my mother to get a chance to experience and I was eager for my daughter to be able to share that with her to see how far the US had come, in spite of all of the challenges that our history had presented.”

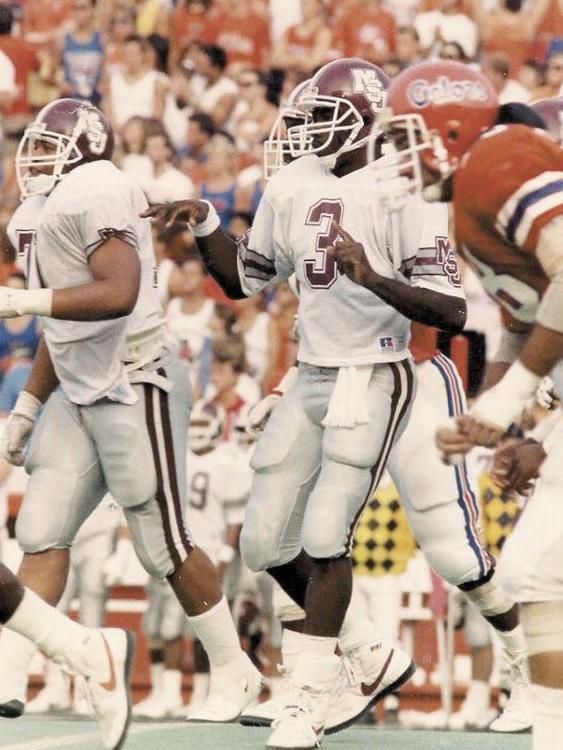

The Williams children were good at school and good at sport, with three earning playing scholarships to various universities. Basketball was a particular strength and the “Williams Clan” dominated the Jackson courts. But Al’s passion was American football and at Mississippi State University he played the glamour position of quarterback. The pinnacle of his football career was leading his team to a win over archrivals South Mississippi in front of a crowd of 50,000. His opposing quarterback that day was a young man named Brett Favre, one of the most successful quarterbacks in NFL history. In his second year in college Williams tore his ACL and the knee injury had a profound impact on him.

“It was probably the first time I realised I was not invincible,” he says. “That was a watershed moment, to remind me that as much as I had a great love and passion for football, it only takes one injury and I’d never be able to perform again.”

Letters from various NFL clubs arrived in the weeks after his graduation but he had already accepted an offer from Chevron. The oil and gas industry had caught his eye at college and he interned with groups including ExxonMobil and NASA.

‘Whether it’s in sports or in work ... each of us has got a role, and every role is equally important’

He started with Chevron in New Orleans, where he helped rebuild infrastructure devastated by Hurricane Andrew. Increasingly senior roles with Chevron followed, taking him around the US and overseas, including postings in Thailand, Indonesia and Kazakhstan.

The football memories have remained strong throughout. He still wears the gold ring handed out by Mississippi State to its players. A football signed by Houston Texans star JJ Watt is on prominent display in Williams’ Perth office.

“As much as I was all in on football, it reminded me that there’s life beyond that and I needed to make sure that I didn’t lose sight of that,” he says.

Williams believes his time in elite-level sport helped set him up for life in the business world and heavily shaped his leadership style: “Whether it’s in sports or in work, it’s a case of our understanding that each of us has got a role, and every role is equally important. If one person doesn’t perform their role, the team doesn’t succeed.”

The task facing Williams in Australia goes well beyond just Chevron’s own workforce, which must now go about the long process of recouping the huge sums invested by Chevron and its partners in Gorgon and Wheatstone. Chevron’s massive investments in Australia were part of a decades-long strategic view that gas would become an increasingly critical part of the global energy mix as the world moved towards cleaner power.

The east coast energy crisis has moved Australia’s oil and gas sector from the business pages to the front page.

Just two weeks after Williams landed in Perth, Western Australia’s independent Environmental Protection Authority unveiled a contentious proposal — since scaled back — that would require all large industrial projects in the state such as future LNG plants to fully offset their entire greenhouse gas emissions.

What should have been a high point for Chevron, when Williams announced the official start-up of one of the world’s largest carbon sequestration projects deep beneath Barrow Island, had some gloss taken off it in late September when the EPA flagged that Chevron and its partners may need to purchase costly carbon offsets to reflect the sequestration project’s delayed start-up.

The taxation regime governing the oil and gas sector in Australia has also been under scrutiny in recent years, and the Chevron boss is expected to take some part in that national conversation.

The Australian oil and gas industry has not covered itself in glory operationally, either. The duplication of LNG infrastructure in WA and Queensland saw the sector responsible for billions of dollars of excessive spending. With a couple of next-generation LNG developments on the table in WA, the various companies continue to struggle to reach agreements to incorporate those new developments into existing LNG plants.

Williams says he wants to be a force for collaboration, starting with plans that would see rival LNG operators better co-operate on sharing and scheduling maintenance crews across rival projects.

“As we work together and we collaborate together, how we go about collaborating with our partners, governments and other community stakeholders, we all will be successful and we will continue to see our industry grow, we will see our community grow, we will continue to see job opportunities created,” he says. “And we will have an even more competitive workforce over time that allows Western Australia and Australia to continue to compete in this global economy.”

Williams wants to ensure Chevron does its part in boosting education outcomes in Australia, particularly in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects.

Almost 50 per cent of students pursuing engineering in the US today, he says, are female, and the oil and gas industry has a role to play in ensuring there is a deep and diverse pool of talent to draw on in Australia.

“It’s not just about us as a company aspiring to see a better representation of society reflected within our companies, but also us being able to partner with associations and institutions and the government to see how we can collectively try to change those outcomes,” he says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout