We could have made the ‘T’ in ChatGPT

Australia led the world in AI until an Abbott government decision. We track down one of our pioneers, now in Germany, to reveal how tantalisingly close we came to being the clever country.

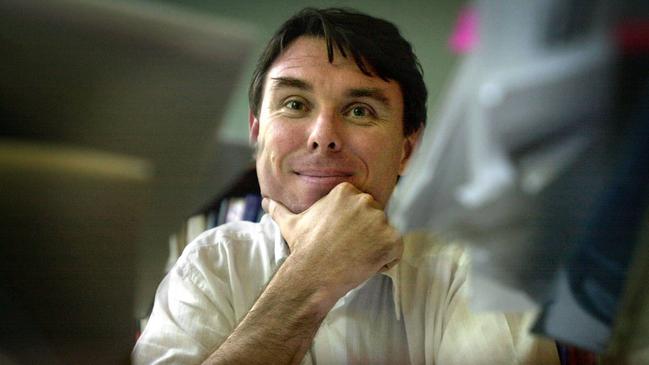

We could have made the ‘T’ in ChatGPT? “Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. For sure,” Professor Robert Williamson says in a broad Australian accent.

The List had asked Professor Williamson – who researches and teaches foundations of machine learning at the University of Tübingen in Germany – whether Australia once had the ability to have invented the ‘transformer’ technology that upended the AI world in the past half decade.

The transformer was a key AI development, just the latest step that led to the current explosion in the technology, ultimately culminating in OpenAI’s generative pre-trained transformer (GPT).

In fact, for the first few months after the launch of ChatGPT, Google – watching the upstart company’s product capture global public imagination – clearly felt it had not received its due and tacked onto its media inquiry emails a section that boasted “in 2017, we developed the Transformer – the grandmother of modern language models”.

Do not miss The List: 100 Innovators 2023 which launches online and in The Australian on Friday, September 15.

Now, about 10 months since ChatGPT was released, it feels like the crest of that generative AI wave has washed over, and companies and governments – after their initial flashy announcements – face the daunting task of doing something about AI.

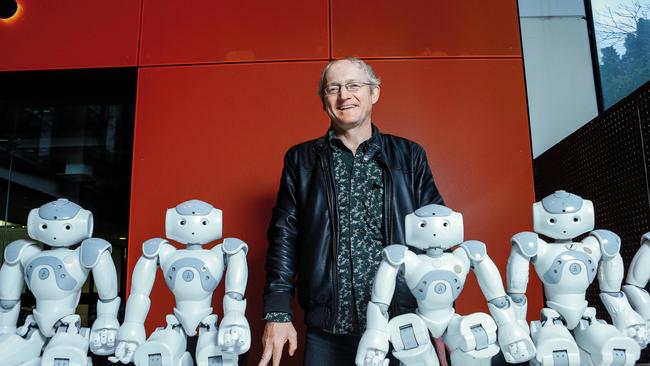

Australia has largely been on the sidelines, eagerly awaiting the latest developments out of the US and Europe. “We are spectators,” says UNSW’s Professor Toby Walsh somewhat forlornly.

Professor Walsh has been a central voice in Australia on the topic of AI, especially in the past year, and highly sought by government and media alike.

“There are lots of unique problems that other people aren’t going to solve for us,” he says. “If you want to use AI to help fight bushfires, right? Satellite imagery to get a real-time view of where the fires are, drones to go off and waterbomb them before fires take hold?

“Well no-one’s going to solve that problem for Australia. That’s an Australian problem. If you want to preserve Australia’s Indigenous languages? No-one’s going to settle that for us.”

Looking at the ground, he says, “NICTA would have made a big dent in that, yes”.

NICTA – the National ICT Authority – is why The List has sought out the likes of Professor Williamson and Professor Walsh.

In a past life, they had led that organisation – “an academic Silicon Valley” – initially set up under the Howard government, and it went on to become one of the world’s top five AI labs before its untimely demise under the Abbott government, which saw it merge with the CSIRO and be renamed Data61.

What had been

“I knew in the marrow of my bones – we were not doing a good job on ICT,” Professor Brian Anderson says over the phone.

Emeritus professor at the ANU, Professor Anderson is speaking from a building at the university that bears his name. As the inaugural chief executive of NICTA, he has a lot to say on the development of AI tech in this country.

“I think the Communications Department thought they were dropping the ball on ICT, and Defence thought they were dropping the ball on ICT. [Then-Communications Minister] Richard Alston had chaired this committee and had looked at – among other things – the CSIRO, and was pretty critical of them.

“CSIRO had a reputation of not being able to move in a terribly agile fashion,” he adds. “And so, I got asked to do a study and write a report for PMSEIC [Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering, and Innovation Council].”

Professor Anderson says it was “axiomatic” for him that Australia should develop its own computing base. “Most people, I think, would accept now that the country’s got to have some deep expertise in ICT.

“Let’s start just with defence – we are under threat with people who want to screw around our election system, who want to read secret communications of the Department of Defence,” he says. “To counter that sort of threat, you need lots and lots of very clever people.

“In ICT, Australian papers emanating from universities were about 20 per cent less cited around the world, whereas in almost all other disciplines of science and engineering, they were within plus or minus maybe three per cent.

“The Australian Research Council… was giving more postdocs in anthropology and archaeology than it was in ICT.”

Professor Anderson therefore set off to prepare the report. “By this stage, I can say I was used to dealing with the government – I was a member of the Prime Minister’s science council, and this was under John Howard, but I’d done that under Paul Keating, and I’d done it even earlier under Bob Hawke and even had something to do with Malcolm Fraser.

“I remember, the day I presented [the report] to PMSEIC… the Prime Minister did say, ‘well it’s clear we’ve got to do something about ICT’.”

And thus, in 2002 NICTA was born – Australia’s Information and Communications Technology Research Centre of Excellence, as it was characterised at the time – with offices in Sydney and Canberra, ideally adjoined to the UNSW and ANU.

“I didn’t particularly want to run NICTA myself,” Professor Anderson admits. “I wanted to get this thing created… I believed personally the country was in some trouble. I was really appalled by how things were.

“Then I realised that I was the one who had credibility with the government. I think it’s fair to say – it might sound arrogant or something – but the bid would have been a lot weaker had I not put my name there. I mean, I was known to the ministers and the senior people in the departments and the advocacy and so on.”

It’s clear that thought had been poured into devising the structure of the organisation.

“One of the design features was to ensure that people – as they can in Germany and France in their successful ICT institutes – join NICTA but have a foot in a university camp somewhere at the same time,” Professor Anderson explains.

“In that way, there’d be a kind of guaranteed flow of students. It was also decided that there was very little to build on in the Australian universities, but what there was should be used as kind of a nucleus. Apart from that, there would be a lot of hiring from overseas.”

What was

Zoom ahead to the early 2010s, and NICTA had become internationally recognised as one of the world’s top AI labs.

“I was told quite explicitly, your mission is to make the machine learning group one of the best in the world,” says Professor Williamson, who led the machine learning group at NICTA and was later its chief executive.

“I consider this as one of my achievements – an external panel, an overseas panel – they said NICTA’s machine learning group was amongst the best five in the world. The other four were Stanford, MIT, Microsoft research and the University of Cambridge.”

NICTA was also pulling serious international talent at this time, he says. “The Stanford guy who was supervising the two Google founders, Jeff Ullman – he used to be on NICTA’s scientific advisory board,” Professor Williamson says.

Jeffrey Ullman is a legendary computer scientist at Stanford University, recipient of the Turing Award, and once the PhD supervisor of Sergey Brin, one of Google’s co-founders.

“We had Stu Feldman, who was the vice president of engineering at Google.”

Feldman was also part of the original group at Bell Labs – more or less the site of Silicon Valley’s genesis – that made the Unix operating system, which still underlies modern consumer operating systems such as MacOS and Linux.

“We had the best people in the world coming each year to check up on us and push us to do better,” Professor Williamson says. “And we listened.”

NICTA was also attracting younger international talent, he adds. He points out Professor Walsh, who concurs.

“I wouldn’t have come without NICTA,” he says. “I would not be in Australia. More than half the people at NICTA were like me. I’d just got a research position in the UK myself. I gave up $2m to come here – NICTA’s worth all that.”

In the early 2010s, Professor Walsh led the optimisation group at NICTA. He, alongside Professor Williamson, reported to Professor Hugh Durrant-Whyte, then the chief executive.

Professor Durrant-Whyte, now the NSW chief scientist, said his first priority when he was headhunted for the role was to clear red tape.

“I think I had a statement – I’m going to remove all the rules, but if you misbehave, I’ll fire you,” he says with a chuckle.

He says the organisation sponsored and graduated about 300 PhD students and, in his four years in the role, it spun out about 20 startups.

Professor Williamson recalls the office’s esprit de corps.

“There’s a very big difference between one PhD student working with one supervisor on their problem in the backwoods versus having a concentrated group, where you’ve got 20 people all working in the same area,” he says.

“It was this very deliberate blend of cultures… it’s not entirely comfortable for anyone, you know? So I’m there more as a pure scientist type, but we had a lot of entrepreneurial people… they view the world in a different kind of way, and you’re kind of banging rocks together, and eventually some sparks kind of fly.

“We were very explicit about this. We talked about the NICTA culture, we tried to be as agile as possible. I could tell when things were going well because I’d hear people laughing and goofing around and joking.”

Demise and the brain drain

Professor Durrant-Whyte left NICTA in 2014 as the Abbott government suddenly pulled funding out of the organisation.

“The driver for that was, ultimately, Tony Abbott deciding not to put us in the forward estimates,” he says. Having said that, we had funding. We had a runway. I was trying to use the opportunity to see what we could do.”

“I’d been headhunted by Amazon at the time,” Professor Williamson says. I didn’t want to move to Seattle. Although I’d done managerial jobs, I’m actually a scientist.

“I explained to the Amazon people that, look, you know, I’m in the hot seat with this organisation at the moment, you know, facing existential threat, and I can’t just walk away. So then we got talking, and so Amazon came back and said, ‘can we buy it?’”

The List is floored when he tells us this. Amazon! So we bring it up with Professor Durrant-Whyte.

“Yes,” he confirms, with a smile and a glint in his eye. We actually had quite a few industries interested in funding NICTA on more of an ongoing basis.”

More industries? What other companies had offered?

He takes a breath, his smile curls up more, and just says, “there was a lot of interest” – a politician’s answer laden with implication.

“The problem was – truthfully – the board got in the way, which is why in the end I really resigned,” Professor Durrant-Whyte says.

“They felt they could get more out of it. They felt that they wanted to do something more with CSIRO. My view is what you would have liked to have happened was the energy that was in NICTA would be transferred into CSIRO. And you would actually have made CSIRO look a lot more like NICTA.

“The problem was they took too long doing it and, by the time the merger happened, NICTA was running out of money – and so CSIRO took over NICTA, not the other way around.”

Professor Williamson was the acting CEO as the merger began. NICTA was already haemorrhaging staff by August 2015, he says, when CSIRO took the reins and it was renamed Data61.

“They immediately fired all our support staff, who were fantastic, and then there was a sorry, miserable story,” he says.

“I think my machine learning group was maybe 32, 35 people at the time we moved, and I kept telling my boss – I’d say, ‘it’s down to 30. Twenty-eight. Twenty-six. Twenty-four’. It just kept going down.

“People just kept leaving because the environment was completely different.

“Below 20. Down to 10.

“I got tired of CSIRO, and CSIRO got tired of me, so I lasted two years in the job there post-merger. The vibe of the place was long since dead and, in hindsight, we should have just shut it down.”

By this point in time, Professor Durrant-Whyte had left NICTA, and later the country to become chief scientist for the ministry of defence in London.

Professor Walsh left in 2016 and returned to his position at UNSW. “I didn’t want to spend my life messed around by all of this existential angst,” he says.

Professor Williamson took up a position at the ANU on his departure.

“When NICTA closed down, they [former colleagues] said to me, ‘Bob, you know, I’ve got this fancy degree now, but there’s really nothing in Australia for me’,” Professor Williamson said. So I’m off to Amazon, I’m off to Facebook, whatever, right?

“One of my group leaders, Alex Smola, is a very eminent machine learning researcher. I first knew Alex as a PhD student. He visited me when I was just a senior lecturer at the ANU. He then came to do a postdoc funded by the government at the ANU.

“We employed him in NICTA. He rapidly got appointed as a professor at the ANU, but then he left – he went to Yahoo, and then to Amazon. He’s a major name in machine learning worldwide.”

Professor Walsh laments the flow of homegrown Australian computing talent today.

“A lot of UNSW AI students, a lot of them go to Silicon Valley,” he says. “Not all of them – Sydney’s got a pretty vibrant startup culture… but a lot of them will go and take jobs overseas.

“In a previous time, they might have stuck around NICTA for a while before leaving to go do something else.

“It’s a loss.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout