Sony’s Kazuo Hirai tunes into a future led by AI and robotics

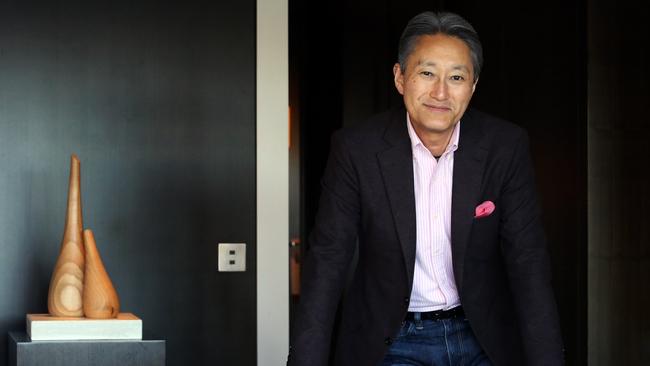

Kazuo Hirai’s time at the top of Sony has seen a return to profitability.

From a hotel suite overlooking Sydney’s Opera House this week, Kazuo Hirai, who heads Sony’s massive global entertainment and electronics empire, sounded positive, purposeful and focused.

He says it’s his first trip to Australia. In 33 years at Sony, he’s never been Down Under before.

“I’ve been CEO now for five years. The first three years was really restructuring. The past two years has been more growth and making sure that we have stable profitability,” Hirai tells The Weekend Australian.

Sony’s story is one that began with a small electronics shop founded inside a Tokyo department store in 1946 exploding into the world’s most comprehensive entertainment business, one that introduced groundbreaking products such as the Walkman music player, flatscreen televisions and the PlayStation games console.

Hirai took command of Sony Corporation from businessman Sir Howard Stringer in 2012.

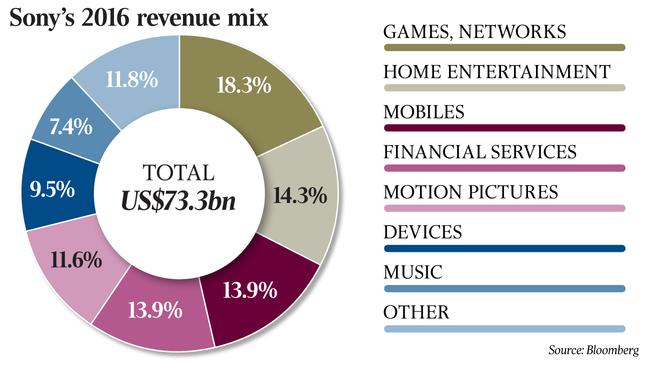

Sony’s businesses are mammoth and comprise film studios and filmmaking, a music and record label empire, and gaming with its PlayStation brand. There’s a huge electronics portfolio. It makes semiconductors, cameras and image sensors, TVs and consumer electronics. It also operates financial services.

As chief executive and president, Hirai is not only proving the right person to handle the rollercoaster ride Sony has endured, which included year after year of losses before his elevation.

Culturally, he is a perfect fit for a Japanese firm with a huge reach in the West. Born in Tokyo in 1960, Hirai, a banker’s son, went to the internationally focused American School in Tokyo and later school in Canada. His English is that of a native speaker.

Hirai may be the right person for the future too, with robotics and artificial intelligence at the top of his agenda.

“It’s a really exciting part of the business and I think it’s got a huge growth potential,” Hirai says.

Sony was once a pioneer in the robotics field with the Aibo artificial intelligence robot dog coming to market in 1999. But it abandoned robotics in 2006, an action that sparked an exodus of expertise.

With more sophisticated AI and machine learning on the agenda again, Hirai is playing the game differently, forming a collaboration with US start-up Cogitai involved in research rather than relying on staff internally.

“They (Cogitai) are able to give us some real insight and advice on how we should be approaching this whole AI space,” he says.

It’s an effort to make sure that we’re getting outside advice without trying to reinvent the wheel, which is exactly the way we used to do things at Sony.”

But he says some of that departed robotic expertise is returning. “A lot of them have actually come back (saying), ‘Let me contribute what I know.’ We have actually recruited some good people from the outside as well.”

Hirai says Sony had established a ¥10 billion ($120 million) innovation fund for new technology. “Areas that we need to go out and acquire, (we) will do exactly that and move away from the traditional Sony way of doing it, which is doing everything internally,” he says.

So what kind of AI is on the agenda? There were reports last year of Sony working on a robot that emotionally bonds with people. Hirai articulated a Sony vision of “moving people emotionally, with products and content and making sure that the people see Sony as being a very innovative, cutting-edge company”.

But there’s more to Sony’s AI agenda than pet robots, with Hirai wanting artificial intelligence implemented right across the company’s portfolio.

What kinds of things could Sony produce? I asked him whether one day we could see a voice recorder that spits out a written transcript, cameras that you ask to adjust settings, that remember and file away the settings or self-compose what you shoot. “Self-composing cameras — you’d be out of a job,” he says.

“I’m not an engineer, but based on what I know, most of the things you have talked about is probably something that we can prototype literally as we speak. The question is can we do it affordably, and reliably, and is it something that consumers really would want? We do a lot of different R&D and I’m exposed to a lot of wacky ideas, so more to come in the space.”

That Sony is working on drones is no secret. In 2015, it forged a partnership with Japan’s ZMP to form Aerosense, which aims to produce commercial drones. Aerosense has released footage of flying prototypes.

“That business is in growth mode,” Hirai says.

He says the joint venture goes beyond making drones to “what type of services we can attach to the drones when they’re flying out, beyond geological surveys”.

Then there’s PlayStation, the gaming platform whose success is credited to the pivotal role played by Hirai. That was as president of Sony Interactive Entertainment and its American arm, before he became overall CEO.

Last year Sony rolled out PlayStation VR, its move into virtual reality gaming. “It’s obviously something that has certainly met and exceeded our expectations,” Hirai says.

But there has been problems with the rollout. “We unfortunately couldn’t keep it in stock in a lot of the markets around the world, which we’re trying to catch up with as quickly as possible.”

Hirai says Sony had sold just under 920,000 PlayStation VR units as of late February.

“The potential for VR, I think, is huge beyond gaming,” he says. “Sony music and Sony pictures already are producing linear content for VR. But even beyond entertainment, I think there is a huge B2B (business-to-business) application in market for VR. Whether we are talking about, for example, a travel agency showing the destinations and having people experience it in VR, before they actually get on the plane.

“Our first order of business though, before we get ahead of ourselves, we need to establish VR first and foremost, and we can do that through video games, and that’s where we are focused on right now, with the understanding that the potential for linear content is there.”

Of course Sony is not alone in implementing VR gaming and will have new competition to meet with Microsoft’s souped up gaming console due late this year and its mixed reality experience. The Japanese corporation is ahead in this market now but will need to contemplate its next move.

TV is another big business for Sony and this year it is spruiking a huge crystal LED canvas built from individual LED tiles whose borders can’t be seen with the naked eye. Then there’s Sony’s A1 OLED 4K TV. The display vibrates to make sound; there’s no need for speakers.

Sony is in the almost unique position of having one arm, Sony Pictures, generate 4K HDR content that can supply its 4K TVs. “Creating content in 4K, and now 4K HDR is obviously one of the priorities.”

Hirai sees streaming as the future of media delivery, so is the newly developed high-density Blu-ray disk already doomed, just an intermediate phase before we stream everything?

“I think that ultimately what you just mentioned will come true. The only thing is that we want people to enjoy content around the world in places where broadband is not necessarily available, or the speed is just not there.”

But there’s been challenges along the way. The company’s film division proved problematic and Sony announced in January a $US960m ($1.3bn) impairment, a huge writedown of its value.

In addition, there were disappointing returns on films such as the new Ghostbusters and Inferno.

“We just were not coming out with the head products, which also had an impact downstream for the home entertainment side of the business as well,” Hirai says.

“That’s why we brought in Tom Rothman, who is now managing our feature film business for us. He’s actually doing a great job in terms of ‘green lighting’ new projects, new movies, and with an emphasis on three things.

“One is controlling the costs, number two is making sure that we place a bigger emphasis on established franchises, and number three is that our motion pictures have more appeal internationally, especially in the Chinese market.”

Then there’s the consumer electronics business with TVs posting losses for 10 years, and the company’s mobile business taking a ¥180bn hit in 2014.

However, in June last year he said all Sony’s consumer electronics businesses would end this year (to March 2017) in the black. We should know soon if this is the case when figures are released.

Hirai’s hopes for a bigger profit this year were hampered by the Kumamoto earthquakes in April last year that set back its manufacture of image sensors and cameras. But Sony is hopeful of a consolidated operating profit of ¥300bn for the fiscal year ending last month, which is similar to the previous year’s. He is shooting for more than ¥500bn this year.

Sony has only ever recorded a profit of that size once before — in 1997. Hirai says achieving it would put Sony on the path to being a highly profitable enterprise.

If he succeeds, that will indeed be a turnaround from the four years of losses Sony endured before he came to the top job and a great personal achievement. It will be an indicator of how successful his strategy is.