National Transport Commission working to 2026 launch date for driverless cars in Australia

It does everything a flesh-and-blood driver would do on the road, just faster and more safely. We test drive Australia’s most advanced driverless car | WATCH

National Transport Commission boss Michael Hopkins has warned that a revised 2026 date to introduce self-driving cars in Australia might not be met when “quite a few moving parts” had to fall into place.

The timeline has slipped repeatedly – fully automated vehicles were supposed to be on the road by 2022 under a superseded chronology – and Mr Hopkins admitted the technology had been subject to “optimism bias”.

But AVs are closer than ever, with carmakers Mercedes Benz and BMW releasing pricey self-driving production models in Europe and the US, and laws being framed at state and federal levels for a launch in this country.

“The challenge that governments have set us is to achieve a balance – we want to be ready for when they’re here, but we also don’t want to try and design regulatory systems that are too different to what’s happening in the rest of the world,” he told The Weekend Australian.

“So we’re avoiding being on the leading edge here. Recently we started working towards late 2026 … to have the framework in place. But there’s still quite a few moving parts to get there.”

On Saturday, The Weekend Australian test-drives the nation’s most advanced driverless cars under development in a state government-backed trial in Queensland.

Zoe2 is a prototype level-4 AV that accelerates sharply to its set maximum of 50km/h and has clocked up 900km in traffic in road tests in the regional centres of Bundaberg and Mt Isa.

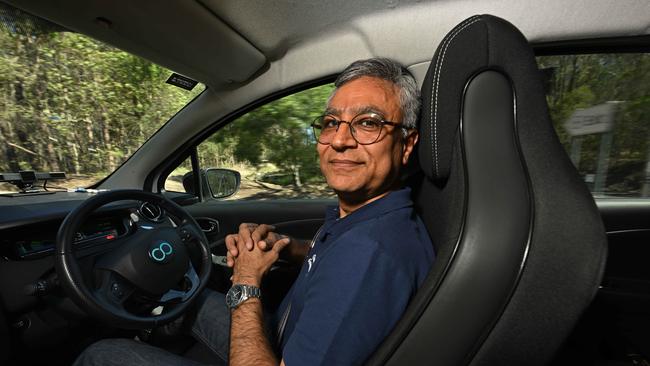

If someone walks into its path, the car will stop itself. Obstacles are avoided, corners rounded. “In a lot of respects Zoe is a safer driver than I could ever be,” said co-developer Amit Trivedi.

Mr Hopkins’ caution reflects the paradox of cars and trucks that can drive themselves: while the technology has advanced to the point that a human could safely hand over control, the road rules, regulatory structures and insurance arrangements lagged behind.

Among the unknowns was how the public would react to sharing the road with AVs, the NTC’s chief executive said. An intergovernmental agreement between the commonwealth and states was being framed to align the required laws, and legislation could go before the nation’s parliaments from 2025.

One option was to establish a new national regulatory agency to take charge of the rollout of AVs, Mr Hopkins said. “There will be a lot of amendments required to state and territory law and we’re doing a fair bit of work to help them do that – essentially to come up with a model law for things like road enforcement.”

The level-3 autonomous cars made by Mercedes-Benz and BMW are optioned on the companies’ flagship models, not available in Australia.

In Germany, California and other US states that allow conditional hands-off driving, this is restricted to designated motorways to a maximum of 60km/h. The intention is for autonomous mode to be engaged in stop-start rush-hour traffic.

A Mercedes-Benz spokeswoman said it would not be possible to retrofit its latest S-class cars sold here for $244,000-plus with the Drive Pilot technology.

Artificial intelligence expert Toby Walsh, of UNSW, said self-driving long-haul trucks and semi-trailers would likely appear sooner on Australian roads than autonomous cars.

Mr Hopkins said there was a “fair bit of confidence” to be taken from the emergence of level-3 capability in production cars after Covid, the global shortage of computer chips and a shift in the R&D effort to electric cars had slowed AV development.

“I think there’s definitely a bit of optimism bias in terms of the timelines we’ve had in the past,” he said. “Whether … that’s just masking the fact that this technology … is taking longer than we thought, I don’t know.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout