Mini satellites set to beam broadband Down Under

The boss of a leading low-orbit satellite company is in talks with Australian firms to bring its new-age broadband service here.

The chief of a leading global company offering low-orbit satellites is in talks with Australian firms to bring its new-age broadband service to Australia.

Conventional satellites in a geostationary orbit of about 36,000km offer slower broadband and suffer from slow response times (latency) due to the long distances that radio signals travel. But a new wave of networks of toaster-sized satellites travelling at 500km upwards from Earth promise to bring gigabit speeds to rural and regional areas and where fast broadband has been hard to install.

OneWeb is among a growing list of firms interested in the technology. They include SpaceX Starlink, Amazon and Facebook. Adelaide-based Fleet is among firms already adapting low-orbit satellites to collecting data from tiny sensors around the world. The technology has been adapted to high-resolution photography of Earth from low space.

Adrian Steckel, chief executive of OneWeb, said Australia was definitely on OneWeb’s agenda and he confirmed he had held talks with local companies.

“Yes we have, and I’m under a non-disclosure agreement so I can’t divulge the names,” he told The Australian

The company plans to put at least two earth stations in Australia. These earth stations would help OneWeb deliver the connectivity that could help connect the rural and remote towns, cities, people across Australia and Southeast Asia, he said.

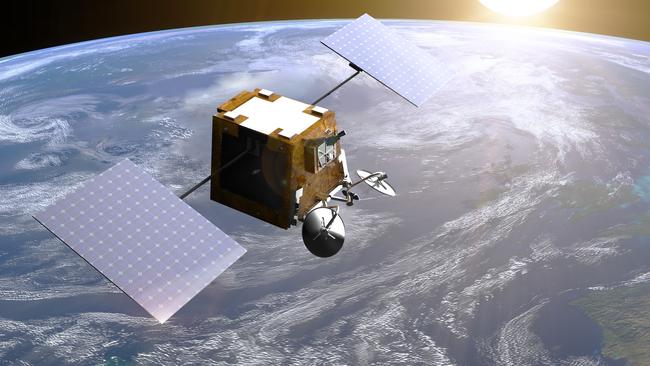

Hundreds of small satellites the size of toasters form a constellation network.

OneWeb launched its first six satellites for its network in French Guiana in February. OneWeb and its joint-venture partner Airbus are preparing a major production of these satellites from June.

“We’re going to be building basically one satellite a day, and we can go up to two satellites a day by the end of the year,” he said. “We’ll be launching 35 satellites a month, every month for the next 20 months, starting December.”

The initial constellation will be 650 satellites orbiting at 1200km with commercial operations starting in 2021. The initial service will provide about one terabit of broadband communications. Mr Steckel’s next target is 2000 satellites by 2026.

It’s the latest communications project by Mr Steckel, a US-Mexican businessman who previously had been involved in rolling out many forms of communication technology in South America.

OneWeb was founded in 2012 by US tech entrepreneur Greg Wyler and initially focused on satellites in distant geostationary orbit. Steckel had spent 25 years in the communications business in Mexico heading firms offering cellular GSM, CDMA, HSPA, LTE and more.

He was also president and CEO of Azteca America, a subsidiary of one of the world’s biggest producers of Spanish-language television globally, and CEO of Unefon, a Mexican teleco with 1.4 million subscribers.

Working with the parent firm Grupo Salinas, he said he invested $US25 million ($35m) in OneWeb in 2015 and $US75m in January 2017. He became CEO of OneWeb last September.

He said the low-orbit satellite push had turned into a multibillion-dollar project.

“It’s taken us a while to get all the right partners on board and to get the engineering right,” he said.

“We saw the potential for low-orbit satellites in 2015 when we made our initial investment.

“We had a lot of experience in using (conventional) satellite and being unsatisfied with them as they have relatively small use cases. And the latency is very big.”

The Mexican conglomerate employed 80,000 people in Mexico at the time.

Through Grupo Salinas he also oversaw the building of fibre networks in Peru and Colombia.

Much of OneWeb’s charter is to deliver fast broadband in the developing world, but OneWeb’s financial backers also want their services available in the developed world, including countries such as Australia. He said it translated into higher GDP and development for all.

“They have different use cases. Aviation, maritime use, and land mobility would be what we most concentrate on in the developed world, and in the developing world, I would be working also with small businesses, and also with telcos to help broaden their networks.

“So you might want to put up a base station with 4G or 5G in a town. But getting the fibre optic cable there may not be practical, and you might connect through our satellite.”

Mr Steckel doesn’t see low-orbit satellite as being in direct competition with fibre networks such as Australia’s National Broadband Network or cellular, although these satellites and 5G are both perfect vehicles for collecting data from the millions of sensors expected to be installed to monitor agriculture, livestock, transport and more.

He sees them as complementary technologies. “If you have fibre in the ground, the fibre will always outperform any other technology. So we want to help broaden the reach of those systems,” he said.

“And we’re all about broadening the use case of satellites. We see a future where you have flat panel antennas in a car, on a train, on a plane and on a boat that are inexpensive, and allow you to get quality broadband at speed.”

In Australia he sees future working with a local partner providing broadband services in regional and remote areas. Antennas needed less power to reach lower-orbit satellites so many earthbound users would communicate directly with them, other installations might involve a node of many users linking to the satellite.

In that vein, his satellites could offer last-mile solutions for Australia’s internet services including the NBN. OneWeb was particularly interested in fast internet connecting schools and community centres.

“We will certainly have ground stations that connect into the NBN in Australia,” he said.

The theoretical throughput of one terabit per second by 2021, or 10,000 connections at 100 megabits per second, means it won’t be taking over broadband delivery, but OneWeb promises to be effective plugging the gaps. Its satellite offering is small compared to plans announced by SpaceX and Amazon but its credibility is that it’s getting satellites launched.

Over time, that capacity would increase as newer “toaster” satellites were launched and the throughput capacity of each satellite would jump 10 times or more.

Mr Steckel said enough satellites would be launched to ensure continued connectivity across the globe with a satellite visible at all times. “We don’t see weather as being an issue,” he said, adding the system would be suited to aiding disaster recovery.

Again he saw low-orbit satellite as complementing 5G providing fast broadband, but he said it could service areas that 5G can’t such as boats at sea.

“These are tools in a toolkit. Generally speaking, there’s no magic, there’s no one tool that solves all problems.”

He said OneWeb was in contact with regulatory bodies to ensure its satellites don’t add to the proliferation of the already astronomical amounts of space junk in orbit. Options included using a robotic arm to collect older satellites or forcing them into lower orbits where they burned up.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout