Is Australia ready for a semiconductor crisis?

The computer chip has been hailed as ‘the new oil’ – the driver of economic progress and production. And while the recent Suez blockage received huge coverage for the $13B impact to global GDP, the approximate $80 billion loss to car manufacturers due to an unexpected shortage in semiconductor chips has gone largely unnoticed.

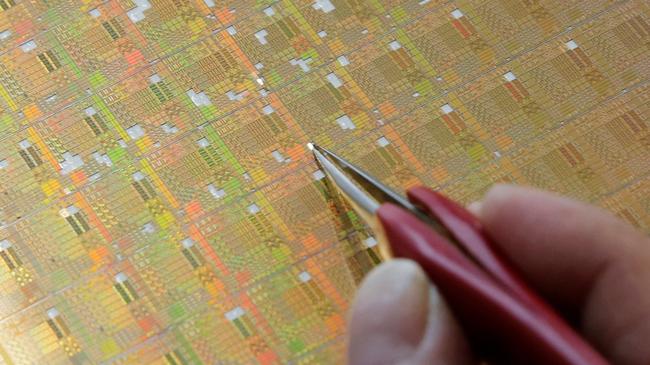

Semiconductor supply chains are far from linear – from chip design to wafer manufacturing and all the way to OEM Assembly. It is complex and capital-intensive, and there are no cheap or easy solutions to solve this problem. It can take semiconductor manufacturers six to nine months to build additional capacity and the fact that global supply is largely dominated by a few countries and companies further exacerbates the issue.

However, as with most problems 2020 has thrown up, there is also opportunity. With COVID recovery progressing at different rates between nations, and tensions between China and the USA escalating, countries are looking for strategic access to semiconductors, including sovereign self-reliance. Considering Australia’s positive rate of recovery, and our abundance of natural primary resources to make the chips, there is ripe opportunity for us to create a new industry and reduce our reliance on global supply chains – all we need is the willingness and drive to do so.

Demand for semiconductors will continue to grow

Next-gen technologies such as edge computing, largely driven by 5G, are exponentially increasing demand for semiconductors. In 2021 the semiconductor industry expects to produce 1 trillion devices. With a global population of 7 billion, that’s 140 devices per person! These will be in our cars, houses, and workplaces. And like Moore’s law, the growth will continue to be exponential. In ten years, the world will need almost double the manufacturing capacity of computer chips than it currently has.

The point about 5G is particularly important, as it will power the technology of tomorrow. By enabling edge computing, 5G will revolutionise our economy and drive productivity gains. However, this revolution is at risk of delay because of the global semiconductor shortage.

Investors have acknowledged this and are aggressively funding the semiconductor industry, resulting in a huge growth in market capitalisation for major industry players. Reliant companies such as Apple and Tesla, are acting quickly to take the design of some of the chips in-house to gain competitive advantage. With the private sector a step ahead, this begets countries to increase their focus on semiconductor sovereignty. The issue is emerging as a catalyst for geopolitical tensions between China and the US, further prompting the need for Australia to get ahead of the game.

Opportunity for Australia

If the COVID vaccine import issues have taught us anything – it’s that we need to reduce import exposure for critical components when we have the capability to do it ourselves. Australia doesn’t currently have scaled domestic microchip manufacturing capacity and is lagging significantly in semiconductor value creation and capture. In fact, components for a chip could travel more than 30,000km and cross more than 70 international orders before making it into your smart light bulb. Seventy-five per cent of current global semiconductor capacity is concentrated in China and South-East Asia, with the US and Japan also reaping substantial economic benefits.

In February, the Biden administration called for US$100 billion to support the production of semiconductors in the US. This follows the announcement by Intel that they will spend $20 billion to build two new chip factories in Arizona. Chinese phone vendors, Oppo and Xiaomi have also begun developing their own 5G mobile chips to decrease reliance on global foundries. So where does Australia stand?

Australia’s key competitive advantage is our local mining of rare earth minerals and abundance of raw materials such as sand as well as the electricity required to produce the chips. While our labour costs are relatively high, semiconductor manufacturing is a highly automated process, reducing competitive disadvantage due to labour cost. Similar to the approach taken by the Netherlands, US and Japan, as a wealthy nation already equipped with the natural resources, we can invest in manufacturing plants, technology and robotics needed to kickstart local industry.

Creating a fully self-sufficient manufacturing capability co-resident with mining avoids the need for supply chain logistics, and international co-operation, even if under licence from global leaders. This would require significant investment and policy support, and could, in the initial stages, result in higher prices for chips and electronics. However, the benefits, not only for the economic development of our country, but as a matter of national security and the effective functioning of our critical infrastructure sectors, will far outweigh the cons.

So the question is are we prepared to invest in order to avoid the ‘semiconductor crisis’?

Jonathan Restarick is Managing Director – Communications, Media and Technology, Accenture ANZ

Last year certainly threw us some curveballs. Lingering in the shadows of larger issues was a powerfully destructive problem – the impending global shortage of the computer chip, or semiconductor, the life blood of the technology that our critical infrastructure – from health to defence to telecommunications, and our everyday devices, are so heavily reliant on.