Google loses antitrust case over search engine dominance

The decision delivers a major antitrust victory to US Justice Department in its effort to rein in Silicon Valley technology giants.

A federal judge ruled that Google engaged in illegal practices to preserve its search engine monopoly, delivering a major antitrust victory to the Justice Department in its effort to rein in Silicon Valley technology giants.

Google, which performs about 90 per cent of the world’s internet searches, exploited its market dominance to stomp out competitors, US District Judge Amit P. Mehta in Washington, DC said in the long-awaited ruling.

“Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” Mehta wrote in his 276-page decision released Monday, in which he also faulted the company for destroying internal messages that could have been useful in the case.

Mehta agreed with the central argument made by the Justice Department and 38 states and territories that Google suppressed competition by paying billions of dollars to operators of web browsers and phone manufacturers to be their default search engine.

That allowed the company to maintain a dominant position in the sponsored text advertising that accompanies search results, Mehta said.

Kent Walker, president of global affairs at Google parent Alphabet, said the company planned to appeal the ruling.

“This decision recognises that Google offers the best search engine, but concludes that we shouldn’t be allowed to make it easily available,” he said in a written statement that quoted complimentary passages from Mehta’s decision. “As this process continues, we will remain focused on making products that people find helpful and easy to use.” Justice Department antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter said the decision “paves the path for innovation for generations to come and protects access to information for all Americans.” Mehta oversaw a 10-week nonjury trial in the case last fall, which featured testimony from Alphabet chief executive Sundar Pichai and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella.

Mehta is now expected to consider what remedies to impose on Google to restore competition. That process could involve more court hearings over several months.

Mehta also criticised Google for automatically erasing chat messages after 24 hours, saying he was “taken aback by the lengths to which Google goes to avoid creating a paper trail for regulators and litigants.” However, the judge said he didn’t impose punishments for that behaviour requested by the government because “the sanctions Plaintiffs request do not move the needle on the court’s assessment of Google’s liability.” Google had argued that its auto-erase policy was explicitly disclosed to plaintiffs years earlier, undercutting the argument that it intended to destroy evidence.

Google’s appeal could mean it will be years until the case is finally resolved, either via a settlement or a final judgment by the courts.

Google is expected to appeal, and additional years of litigation could be ahead. Nonetheless, Mehta’s ruling could force Google to change how it does business as the company is under heightened scrutiny at home and abroad. The European Union’s competition regulators recently announced a renewed investigation into Google’s app store practices, and the company faces a September trial in a different antitrust case in which the Justice Department alleges Google illegally monopolises the market for technology used to broker digital advertising.

“This is a really big moment for that movement to bring big tech under control,” said Rebecca Haw Allensworth, an antitrust professor at Vanderbilt University Law School who has written critically about Google and other tech companies.

Allensworth said Mehta would most likely issue an injunction against Google’s search deals or require that users affirmatively choose which search engine they use in browsers, rather than automatically using one that paid for its default position.

It is possible the judge could limit when and how Google pays for its search engine to get prime placement on devices such as Apple’s iPhones. In 2022, Google paid Apple $20 billion to maintain its default status on Apple devices, court documents show.

Shares in Alphabet sank slightly following the midday decision and closed down nearly 5% Monday, part of a broader sell-off in tech stocks.

The case before Mehta dates back to October 2020, when the Justice Department sued Google during the final months of the Trump administration. A bipartisan group of state attorneys general also sued the company and the two cases were consolidated.

The Google case was the first of several antitrust lawsuits the federal government filed against some of the nation’s leading tech companies, following years of criticism that U.S. enforcers have been too timid in providing a check on their growing dominance.

Monday’s decision could give a boost to pending government cases alleging anticompetitive conduct by Apple, Amazon.com, and Facebook parent Meta Platforms.

Google is also waiting for a California judge to prescribe changes to its mobile app store business after in December losing a case brought by Fortnite maker Epic Games. It plans to appeal.

While the search-focused case dates back to the Trump era, it has been a priority for President Biden’s Justice Department, which has pledged to be aggressive in policing dominant firms. Kanter is a longtime Google foe who has criticised the concentration of power and influence among a handful of technology companies.

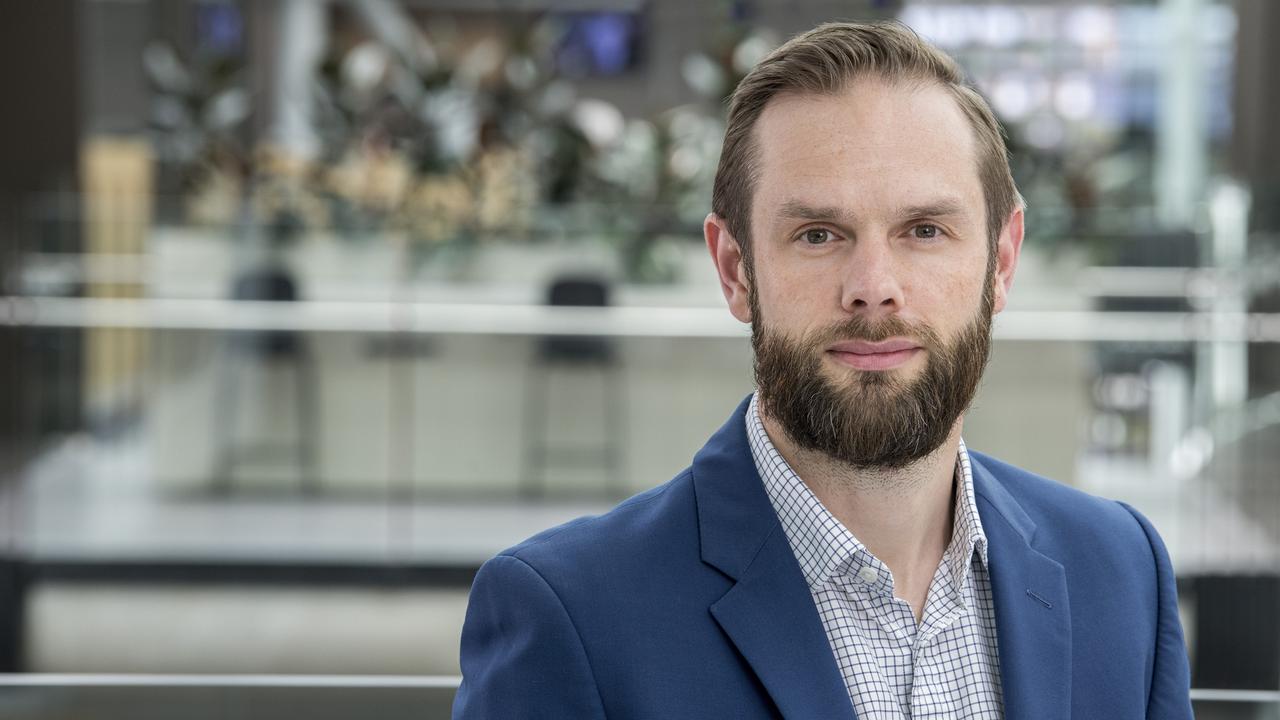

He brought the department’s second sweeping antitrust lawsuit against Google, focused on its advertising technology. That case, set for a nonjury trial beginning Sept. 9 in Virginia, alleges Google has an illegal monopoly on the tools that power the $US250 billion digital advertising market. The Justice Department accuses Google of distorting the auctions used to place ads on websites and of locking customers into using Google’s products – claims the company denies.

In March, Kanter accused Apple of using unlawful tactics to lock consumers into its iPhone ecosystem. Apple has said the lawsuit is legally and factually wrong.

The Federal Trade Commission, which shares antitrust enforcement authority with the Justice Department, is meanwhile pressing forward with a lawsuit that seeks to unwind Meta’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp on the grounds that the company sought to foreclose competition by buying up potential rivals. Meta has denied the FTC’s claims, saying it faces fierce competition and isn’t a monopoly.

The FTC also sued Amazon last year, alleging it wields monopoly power that keeps prices artificially high, a claim the retail giant denies.

The government’s offensive against Google has drawn comparisons to the Justice Department’s landmark antitrust case against Microsoft in 1998, the last similar monopolization case against a top U.S. tech firm. The department won that case, which eventually resulted in a settlement that required numerous changes to Microsoft’s business practices.

Dow Jones