From clothes to rubbish and plastic recycling, these ideas are making a difference

In Sydney, Giorgio Baracchi is leaning into the ‘garbo man’ tag as his rubbish collection business booms while in Darwin, Tanya Egerton is rolling out a remote op shops revolution | SEE WHO MADE THE LIST

Not many people can convince a council to pay for services it already does regularly, but Giorgio Baracchi can, and did.

The young Italian founder from Sydney, who earned his stripes in management consulting at Bain & Company, has spent years testing different plays in the recycling market only to land upon one that does almost exactly what the council had done for years, only better.

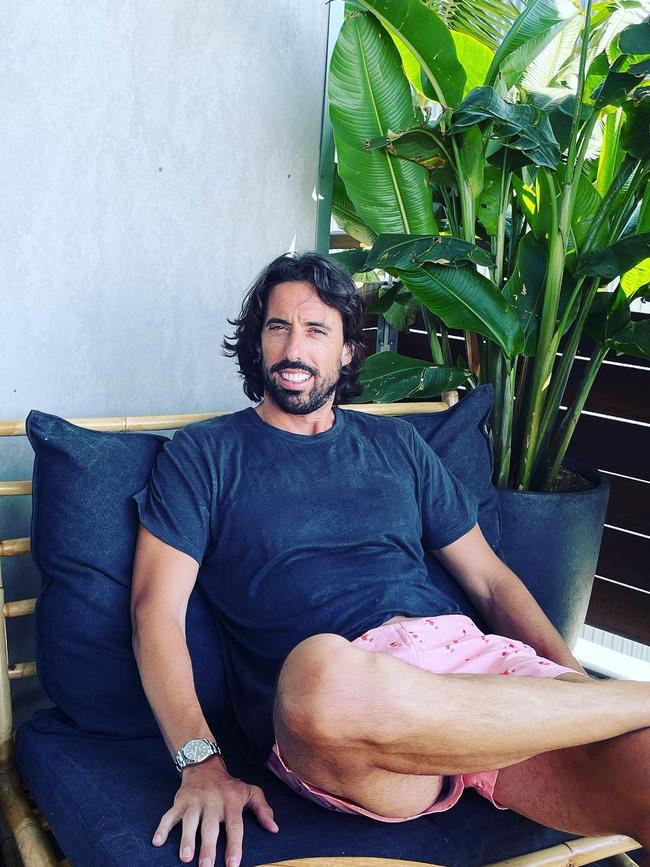

Baracchi, who playfully calls himself a ‘garbo’ on social media, founded RecycleSmart which he describes as the Uber Eats of rubbish collection, if you like.

It pays people to drive around collecting trash, which is then sorted and sold to suppliers and partners. It tackles a vast range of products from used coffee cups – which it turns into road base – to batteries, contact lenses, coffee pods, broken shoes and textiles.

SEE WHO MADE THE LIST: TOP 100 GREEN ENERGY PLAYERS

“We collect pretty much 50 to 60 per cent of your daily waste production and we do the right thing with it,” Baracchi says.

The business operates for both commercial and residential customers, some of whom even pay to have their trash collected.

One of its largest demographics is women, many of whom are more concerned than men as to where their trash ends up.

“It’s the Uber Eats demographic,” Baracchi says. “It’s young people, mostly women but some men too, who are busy and clearly care about the environment but cannot spend their whole day trying to find a solution to recycle a battery.”

To further entice consumers to take up the business, RecycleSmart even has its own “return and earn” bottle scheme which pays users 10c for every bottle it collects from their house.

This is an article from The List: 100 Top Energy Players 2024, which is announced in full on November 22.

RecycleSmart charges residential customers $7 a bag but if they live within one of the councils it works with – such as Brisbane City Council and several councils in Sydney including Burwood, Mosman and Sutherland Shire – they can get two pick-ups a month for free.

On the commercial side, Baracchi says every “cool” office in Sydney has jumped on board the program, which offers packages including an “essentials option” that provides a 60L bin and 26 pick-ups a year that can be scheduled by app, and a “premium option”, which offers the same service but a bin made from 50 per cent recycled materials and a five-year warranty.

Those “cool” companies include Australian tech giant Canva, which has diverted 979kg of waste from landfill, had 875 bags collected and prevented 73,201kg of emissions, according to RecycleSmart. Canva’s beverage and front of house lead Dan Bloom says: “With RecycleSmart, we have been able to get rid of our problematic waste by using their easy and reliable app.”

Abdullah Ramay, Paco Industries

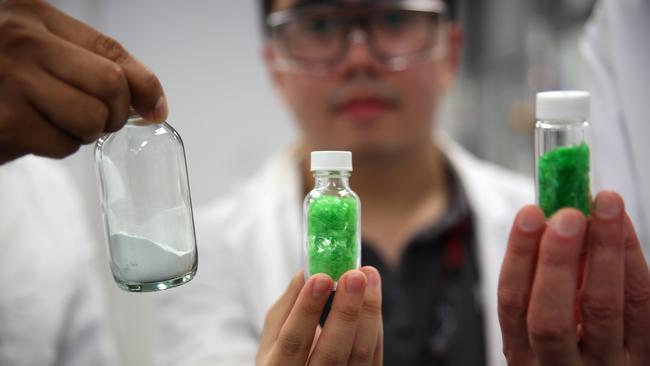

Another Australian invention set to change the way we recycle products is made by start-up Paco Industries, a spinout of impact investment fund FP Paradigm’s commercialisation arm. In collaboration with researchers from the University of NSW, it has developed a solvent that allows contaminated plastic to be recycled over and over again, having overcome one of the biggest barriers to the repeated recycling of polyethylene terephthalate plastic (PET), which degrades each time it is reprocessed.

Revenue could jump as much as $100m if Paco Industries can successfully commercialise the idea, with some major food manufacturers including biscuit giant Arnott’s and speciality coffee roaster Pablo & Rusty’s having already agreed to use the tech if it can be delivered at scale.

Arnott’s has signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to support further research and development. Coffee giant Pablo & Rusty has signed a similar MoU, and its chief executive, Abdullah Ramay, says it’s logical for coffee companies to want to invest in the recycling space.

Most “recyclable” plastics placed in yellow bins actually end up in landfill, says Paco Industries head of commercial Steven Commerford.

“Typically plastic is a downward spiral, much like paper recycling, so the fibres or the chains become shorter and shorter over time,” he says.

“[With our solvent] we’re able to recycle at the same level and it means that we’re able to essentially take food-grade PET plastic and make it into food-grade PET plastic again.”

With capacity for about 1000 tonnes of plastic production annually, Paco Industries is on the hunt for a larger facility that can produce 20,000 to 30,000 tonnes, equivalent to 5 per cent of Australia’s plastic production.

Tanya Egerton, Circulanation

Some of Australia’s biggest household and clothing brands will provide unsold goods to remote Australian communities as part of a radical “circular economy” project based out of Darwin.

The goods will be distributed through Reuse and Recycling hubs by the not-for-profit Circulanation, which has set up a network of about 30 op shops selling donated clothing and goods in remote Indigenous communities. The hub opened in September.

In August this year, Circulanation chief executive Tanya Egerton was named the national winner of the 2024 Rural Women’s Award run by AgriFutures Australia for her work in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. The non-Indigenous woman is a former marketing manager at Patagonia and has been working in the Territory for about a decade, initially focusing on Indigenous business development.

As part of the recycling project, brands redirect excess goods to the Remote OpShop Project as an alternative to landfill or offshoring the unwanted material. “I am very aware that we are facing an environmental crisis in Australia,” Egerton says. About 200,000 tonnes of textile-based landfill is created every year, yet remote communities are deprived of household and clothing goods, she says.

Her Remote OpShop Project began after women in a remote community asked for help to set up an enterprise to support their arts centre. The shop was launched with clothes sourced by a network of Facebook followers in urban Australia and the idea spread quickly as other communities sought Egerton’s help.

Egerton says the op shops empowered remote communities. “People in remote areas have been forced to participate in their own lives for so long and owning and leading something in a remote community is very rare,” she says. “When you give people a platform and you give people resources… people stand up and lead.”

The remote op shops offer a platform for small business training with the shops owned and operated by women in the communities. They were set up as social enterprises with the money invested back in local cultural projects.

The risks of recycling

While the good of recycling is often spoken about, many fail to realise the dangers present in the production lines. And, over the past several years, a new threat has emerged around vapes, with the biggest danger to those doing the recycling work.

The lithium ion-battery powered devices, the majority of which are imported from countries with lax regulations on lithium ion batteries, are sparking fires on the side of the road, in waste collection trucks and inside plants.

The fires are shutting down recycling plants for days at a time, says Suzanne Toumbourou, chief executive of the Australian Council of Recycling. Toumbourou is one of few Australians who advocates for the safety of the nation’s recycling workers, many of whom spend their days exposed to toxic chemicals, rotten foods and malfunctioning battery-powered devices, some of which retain their charge and can be set off when being processed.

While the government has been gung-ho about banning vapes, it has neglected to consider the safe collection of them, she says. The products are often marketed as disposable but that’s far from the truth, Toumbourou says.

“What we’re seeing as a sector is over 10,000 fires a year across all parts of the waste and recycling system,” she says. That includes waste trucks and plants. One of the major issues is around the chemistry of the batteries in these devices. “With battery chemistries at the moment, they are very diverse. It’s often locked up in IP, and not well disclosed and how volatile they are isn’t well understood,” Toumbourou says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout