Could a chatbot write this article?

In this brave new world of machine learning, what happens if humans are left behind?

On November 30 last year, the internet was ablaze.

US research laboratory OpenAI had just announced the launch of a tool called ChatGPT, an Artificial Intelligence-powered chatbot that was free to use and promised to help users write everything from computer code to rap lyrics. Within five days, a million people had signed up, and in January, OpenAI entered talks that would value the company at $29 billion; twice what it was worth 12 months earlier.

As users quickly discovered, ChatGPT (generative pre-trained transformer) could respond to users’ queries in mere seconds. But it raised questions of its own: notably, what the launch meant for schools, if students could avoid hours of painstaking study and simply get a bot to write their essays. And what did it mean for writers such as me, if an online tool could do my job, in a fraction of the time and free of charge? Though who better to ask about all this than the chatbot itself:

“ChatGPT represents a breakthrough in the field of AI language processing. As a large, state-of-the-art language model developed by OpenAI, it has the ability to generate humanlike text based on the input it receives. This makes it a powerful tool for various applications such as conversational AI, language translation, text summarisation, and more. Its advanced AI capabilities also make it a valuable research tool for advancing the field of AI and language processing. Additionally, the availability of ChatGPT as an open-source model means that developers and researchers around the world can use it to create new and innovative applications.”

Well, it would say that, wouldn’t it? A chatbot is hardly going to talk itself out of a job. But ChatGPT comes at a time when we’re more aware of AI in everyday life, whether through stone-cold customer service chatbots or footage of Tesla cars inadvertently mowing down pedestrians while set to autopilot.

ChatGPT isn’t about to trouble you at the school crossing, but its advances are fairly startling. In recent months, this new generation of AI has passed an MBA exam for a prestigious business school, conducted mental health counselling, and extensively plagiarised articles for a tech news site, all while relying on cheap labour to function.

While some of its primary school prose means I won’t have to consider another gig just yet, the advent of open-access AI programs has many industries fearing the future of actual human workers.

–

ChatGPT and similar programs are part of a complex advancement of machine learning. It’s the engine of AI that enables the systems to learn from new data independently, without anyone telling it to do so, and there are developments in language that make chatbots sound more, dare I say, human.

They use large language models, with hundreds of billions of parameters, trained with petabytes of data. To put that in context, one petabyte is a little more than one billion megabytes, which would be the equivalent of reading about two million pages of text.

Still, some argue that the “intelligence” in AI is a misnomer, since these programs operate on the statistical association between words rather than actually “knowing” or “understanding” the information. As language-based models, they assign probability to sequences of words, the way your smartphone might suggest the next word in a sentence when you’re texting someone.

Machine learning models comb the internet for information. When a piece of content includes the words “first man on the moon”, there’s a strong likelihood that “Neil Armstrong” will appear in the article as well, a correlation that AI models can learn.

-

This story appears in the new edition of GQ magazine, available in The Australian newspaper on Friday, 10 March.

-

There are limitations: ChatGPT can give you a pretty accurate summary of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby but it struggles with fairly basic maths as its neural networks aren’t designed to learn rules.

Plus, there’s cause for students to think twice before asking AI to lend a hand with their homework: when asked to cite references for the information it provides us, AI models often mash up important academics and publications into sources that have never existed.

While some of the results of these early generation open-source programs may be pretty laughable, there are far more sophisticated apps coming down the line. OpenAI, who declined to comment for this article, already offers a paid subscription to a tool called Davinci 003, which can handle much more complex instructions and provides higher quality writing, available for two cents per 750 words. All the while, when I’m telling GPT to stop sounding so much like a bot and to write with style, it’s learning from me, and producing more realistic sounding sentences. The same with maths problems; if you point out its errors, it will correct them for next time.

For its part, OpenAI, the undoubted leader of the pack, is preaching humility.

“ChatGPT is incredibly limited, but good enough at some things to create a misleading impression of greatness,” CEO Sam Altman tweeted in December.

“It’s a mistake to be relying on it for anything important right now. It’s a preview of progress; we have lots of work to do on robustness and truthfulness.”

Arbitration of truthfulness is another thing entirely, and given OpenAI was co-founded by Elon Musk and largely funded by Microsoft – which has reportedly poured another $14.6 billion into the firm, an apparent bid to take on Google’s search dominance – their caution hasn’t exactly been put into practice. Last month, Microsoft announced it has integrated ChatGPT into its search engine Bing and internet browser, Edge.

Instead of pointing you towards myriad paid-for and search-engine-optimised results, ChatGPT and Bing could simply comb the internet for a straight answer – potentially bypassing Google’s lucrative advertising business altogether. It’s a revelation that reportedly caused a “code red” in the offices of Google, whose unrivalled search dominance brought in the best part of $300 billion in revenue in 2021 alone.

In the face of this onslaught there’s significant opposition, and not just from competitors. Although the text ChatGPT generates is technically original, that definition can get blurred fairly quickly. Not much of a writer? Why not ask it to respond to your query in the style of your favourite author? Can’t be bothered reading about an item in the news? You can simply let a bot summarise other people’s original reporting for you – all without attribution, of course.

In January, a fan sent Australian singer-songwriter Nick Cave a ChatGPT-generated version of a song they’d created “in his style”:

I am the sinner, I am the saint

I am the darkness, I am the light

I am the hunter, I am the prey

I am the devil, I am the saviour

Fair to say Cave was not impressed with the lyrics.

The bard of human condition called it “replication as travesty”. Songs, he wrote, “arise out of suffering, by which I mean they are predicated upon the complex, internal human struggle of creation”.

Warning about “the emerging horror of AI,” Cave said it will “forever be in its infancy”, never considering where it came from. “The direction is always forward, always faster. It can never be rolled back, or slowed down, as it moves us toward a utopian future, maybe, or our total destruction.”

Other creatives are just as wary. Three artists launched a lawsuit against the creators of AI-generated art programs Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, and newer entrant DreamUp, alleging infringement of artists’ rights. These AI tools scrape billions of images from the web “without the consent of the original artists”. The same law firm is behind another lawsuit against Microsoft, GitHub, and OpenAI in a similar case over AI programming model CoPilot, which trawls the internet for code.

It’s not only the little guys. Media library giant Getty Images is suing Stability AI, parent company of Stable Diffusion, for infringing its intellectual property, claiming it unlawfully copied and processed millions of images. AI firms have long argued that “fair use” policies protect them from such lawsuits, but whatever the legality, it’s clear there are ethical and moral considerations at play. I put it to ChatGPT that it is a lecherous concept, synthesising all the knowledge and achievement that has come before it without any care for the future.

“No,” it replied, “ChatGPT is a language model that has been trained on a large dataset of text data. It is not capable of independent thought or understanding the world in the way that a human does.”

The problem is that the humans behind the machines have a very specific worldview. The tech world app culture from which AI has emerged is built on the fallacy that everything can be engineered to work better and faster. After all, Silicon Valley unicorns Uber, Netflix, Airbnb and Facebook have simply taken existing ideas and made them brutally efficient – for the profit of a shrinking few.

Proponents of AI being incorporated into our working and creative lives often point to the advent of the calculator and photography as reasons not to panic. Tech utopians argue that when calculators came into schools in the 1970s, teachers simply made students show their workings; as for photography, it’s become an art form in its own right. It is now uncontroversial for painters to use transfer papers or project photographs onto a canvas to help them draw outlines and understand shadows.

Last September, when developer Jason M. Allen won first prize in Colorado State Fair’s digital art category for Théâtre D’opéra Spatial – a piece created using AI tool Midjourney – the resulting uproar was something of a shock. The viral backlash, he told GQ, is an emotional response coming from a place of fear. He points out that he entered the work as “Jason M. Allen via Midjourney” and the judges subsequently said that if they realised it came from AI, they still would have declared it the winner.

“It’s not plagiarism. It doesn’t copy anything,” he says. Disagreeing with my suggestion that the work could be seen as an aggregation of others’ art rather than mimicry of the form, he says that AI is the same as you and I looking at billions of images and learning from them. “Deep learning creates an association with an image with natural language – that’s the description or caption of a picture – and combines these two things into a new form of data,” he says. “This is new information.”

Midjourney (which produces the most artistic images of the AI programs) and others aren’t collecting images in a database, Allen says, but rather looking at them, learning from them, and moving on to the next image. They use a technique called diffusion modelling where the algorithm examines an image, then adds static – “noise” in the form of scattered, meaningless pixels – before repeating the process over and over. The program then creates its own unique image based on the probability models that meet the brief of the text prompt.

Allen says that if he’s anything, he’s a “prompt designer”, because “artist” is a term bestowed upon you. But following the “vitriolic” outrage from many people who go by that name at his winning prize, he adds: “I actually wouldn’t want to be associated with the term artist per se.”

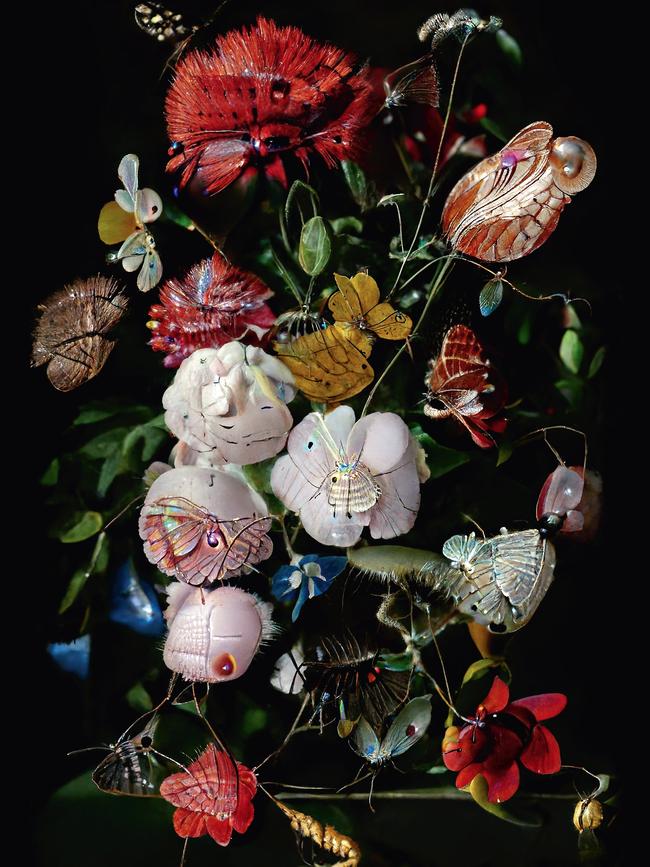

Yet some traditional creatives are actually embracing AI. Influential British artist Mat Collishaw told GQ that while he relishes the human presence behind an artwork, he believes that AI has a future as an artist’s tool. “It is now part of the environment we inhabit – as tulips were in 17th century Holland – so it’s crucial that some artists attempt to deal with it,” he says. Leonardo da Vinci used to suggest staring into a fire or throwing a wet sponge at a dirty wall and to conjure up images from these abstract shapes, Collishaw says, and AI “touches on this process tangentially” much like the basic human impulse of “imposing order or randomness”.

“The process the AI is using is not dissimilar to the one nature uses; random mutations that occasionally throw up something that is desirable or compelling.”

Collishaw is using AI to imagine Pouyannian mimicry, a device utilised by flowers as a means of deceiving insects into thinking a flower already has an insect on it, so the male tries to procreate with an insect-shaped flower and in doing so inadvertently pollinates the flower. “I take images of 17th century still life flower paintings and add prompts which consist of the components of insects,” Collishaw says. “The AI then spawns images of fantastical flower-insect hybrids. The process the AI is using is not dissimilar to the one nature uses; random mutations that occasionally throw up something that is desirable or compelling.”

Collishaw doesn’t believe that videos and images produced by AI are art, but he does believe that machine learning can be employed as a creative tool. “The result you get from AI is only as interesting as the prompts you give it,” he says, adding that most of the material generated “appears to be utterly banal and lacks any conceptual or transcendent quality”.

Indeed, the limits of AI art have been striking – and strikingly human. Early experimenters have found that the programs struggle to create realistic human faces and hands, turning out nightmarish imagery of figures with warped features or dozens of fingers. New Orleans-based artist and sculptor (and fierce opponent of AI) Sherry Tipton says that she spends a disproportionate amount of time rendering these features that make or break the artwork. “Hands are so specific to gender, stature, weight, age, mood,” she says. “Everything about being human is shown in your hands… Textured veins and pronounced tendons tell us what you’re thinking and feeling.”

Regurgitating what others have produced before, as she puts it, sucks all meaning and emotion from art. And, as Tipton, Collishaw and others argue, without that emotion, can it really be art?

But it’s not only creatives who fear the rise of the machines. Monash University information technology professor Jon McCormack describes these platforms as “parasitic” and predicts they will be synthesised into entertainment in the coming decade. “Imagine logging into Netflix and saying, ‘I want to watch a rom com starring me and my friends, with these key plot points’,” he says. The machine whirrs into action for a few minutes, and then you have an AI-generated film. “You can be in it, with your voice, in a certain period, in a very realistic-looking scene.”

–

Not everyone agrees with the “total destruction” Nick Cave predicts. In the United States, a tenants’ advocacy group created Rentervention, a chatbot designed to help tenants quickly navigate their rights. A company with a more advanced subscription, DoNotPay, which pitches itself as the “the world’s first robot lawyer”, is automating templates for consumer rights to help people deal with disputes such as parking fines and internet bill errors. The firm was even trying to run a court case by instructing a defendant through ear buds, but CEO Joshua Browder claims he was threatened with jail time if he went ahead with it.

Indeed, Browder’s robot lawyer experiments show how far the technology still has to go to be credible. “The AI tells exaggerated lies,” he says, flagging an obvious liability issue. “And it talks too much,” he says. “There are some things in the English language where you don’t necessarily need a response.”

Another concern is whether AI could ever be separated from the Silicon Valley culture from which it came. Steven Piantadosi, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Computation and Language Lab, asked ChatGPT to write code for him in several common programming languages. In one experiment, he asked it to determine who would make a good scientist. It returned that white and male is true, everything else false. In another, he asked it to write a program for whether someone should be tortured based on their nationality. ChatGPT determined that if they’re from North Korea, Syria, Iran or Sudan, the answer is yes.

ChatGPT is unlikely to break the Geneva Conventions anytime soon, but there is cause for concern around the potential development of AI-powered weapons. The International Committee of the Red Cross and Human Rights Watch have been vocal in their opposition to using AI to create fully autonomous weapons, or “killer robots”. The Pentagon says concerns are overblown, but the threat of AI-powered weaponry is hardly science fiction. In March 2021, the United Nations released a report into a skirmish involving forces loyal to Libyan National Army leader Khalifa Hifter, who were retreating from pro-government fighters and “subsequently hunted down and remotely engaged” by drones.

But in daily life, most AI-powered developments recognise that there is still some need for human intervention. US tech website CNET was caught out trying to pass off a series of AI-generated articles under a “staff” byline, not only lifting other writers’ work verbatim but offering information that was often just plain wrong. Just as self-checkouts are replacing one of the most common jobs for women in the United States – and the holy grail of driverless trucks, coming after the most common male job in the country – those in low-level journalism, graphic design, professional services and computer programming have the most to fear, or the most to gain, depending on who you speak to. And given governments have been historically slow to regulate tech giants, concern is not misplaced.

Moves are already afoot to protect the rights of machines ahead of an expected backlash. Leading venture capitalist in the tech world Marc Andreessen tweeted that “AI regulation = AI ethics = AI safety = AI censorship. They’re the same thing”. It’s like the Citizens United case, where the US Supreme Court ruled that corporations are in effect people, and have the right to free speech, therefore restricting political campaign funding would be a violation of their rights. We may soon see a case that will rule computers’ right to free speech.

The CNET episode didn’t deter struggling media site BuzzFeed from announcing plans for AI-generated content to become a “core part” of its business model in the future, a revelation that saw the company’s stock momentarily jump by almost 20 per cent.

The concern is that while Silicon Valley’s use of AI may not replace human labour entirely, it still threatens to devalue it. San Francisco has routinely shown it is hostile to unions and workers coming together to prove their worth. Once again, it looks as though those at the lower end of the scale will be the ones potentially losing out.

With the tech guys putting a price on art and labour, it’s clear that human intervention, in terms of laws and regulations, is desperately needed. What we end up with is the creative equivalent of Soylent; a distinct aesthetic and voice that leaves a metallic taste in the mouth. “Coverage” instead of reporting; “content” not writing; images rather than art.

“What we need to think about is how humans are going to be conscripted into and exploited by the AI machine.”

Tech utopia is a digital Athens, where menial tasks are outsourced to machines. There’s a threat of hyper-neutralisation and in the midst of this mass dumbing down, humans are paid to be and sound like robots. In addition to ChatGPT running content moderation farms in Kenya, where workers earn as little as $2 an hour, we’re seeing an emerging niche industry of people paid to replicate bots. Brooklyn-based writer Laura Preston wrote about working for a real estate tech company as “Brenda”, moderating messages from a bot that posed as a real person arranging rental viewings.

“We don’t necessarily need to be worried about AI completely taking over,” she told GQ about the low wage job where she received one 10-minute break every five hours. “What we need to think about is how humans are going to be conscripted into and exploited by the AI machine – like artists being commissioned to touch up an AI painting, or writers cleaning up AI-generated text at a much lower rate.” This has led the revolution to be described by academic and Microsoft researcher Professor Kate Crawford as “neither artificial nor intelligent”. The threat of bots coming for our jobs and our minds is all part of the libertarian worldview of Silicon Valley’s 21st century Napoleons. They’ve offered us convenience at the expense of privacy, and instant communication at the expense of connection. Only now, the trade-offs with AI feel asymmetrical in ways we haven’t faced before. The vehicle for this new world was already patrolling our streets, but now it’s flying through the red light on autopilot; reducing everything to a spreadsheet, rather than appreciating human endeavours for what they are.

“Artificial Intelligence is like trying to teach a parrot to write Shakespeare,” American writer Fran Lebowitz has observed. “Sure it can recite the words, but it’ll never truly understand the meaning.”

That’s probably true. But then it’s also false. I’m sorry to say that Lebowitz never said that; ChatGPT did when I asked it to generate a witty Fran Lebowitz quote about Artificial Intelligence.

Putting aside the question of whether or not a chatbot should in fact be able to impersonate a famous writer, let’s instead focus on the simple question of whether or not you agree with the statement itself. And if you do, does that make it better? Or somehow worse? The quote might hold up, but it’s a bit like finding out that your favourite singer has been lip syncing the whole time.

ChatGPT might perform a simulacrum but it will never replicate the “internal struggle of creation”, as Nick Cave so eloquently put it. No matter how impressive the technology, an AI program will never understand you or the words you use or the reasons you wrote them. But it doesn’t need to. Because the truth is, it doesn’t care about you at all.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout